A key problem in monetary theory is how to explain and conceptualize the demand for money. In the Keynesian system, liquidity preference plays a key role (Keynes 1936; Hicks 1937), while monetarists focus on velocity in their demand functions (Fisher 1922; Friedman 1956). The Cambridge tradition, for its part, conceives of demand for money as demand to hold cash balances worth some fraction of the flow of income (Marshall 1923, 45–46; Pigou 1917; Robertson 1948, 180–81). In general, economists trace the demand for money to different sources or motives, usually under three headings: transaction demand, speculative or asset demand, and precautionary demand (Timberlake 1965; Laidler 1993). Disagreements arise over which motive is the most important—the Keynesians stress asset demand (liquidity preference) and quantity theorists usually emphasize transaction demand. Precautionary demand for money is often an afterthought, although Hicks (1935) on theoretical and Friedman (1969) on empirical grounds have brought it to the fore.

A competing explanation of the demand for money is presented by the causal-realist tradition in economics (Salerno 2010b), whose most well-known representatives are the Austrian economists. In this tradition, which takes a pure cash-balance approach, demand for money is always conceived of as a demand to hold (Cannan 1921, 1932). This is not, however, to be confused with the Cambridge approach. Instead of conceiving of the demand for money in the form of an equation, where individual demand is determined as a fraction of the total stock, causal-realist analysis traces it back to the value scales of the individuals acting in the market and thus places it under the general laws of value and the principle of marginal utility (Mises 1953, 1990). Pioneered by Menger (2007), causal-realist analysis traces the value of money, as it does for all economic phenomena, back to individual decision-making (Hülsmann 2012, 3).

There is a rich literature on the production or supply of money in this tradition which reviews different institutional settings of money production (White 1999; Hülsmann 2008) and the consequences of fiduciary media—that is, the supply of money through the banking system (Selgin 1988; Horwitz 2000; Rothbard 2008)—but comparatively little has been written on the demand for money. The tripartite division of motives for demanding money is clearly rejected. Instead, the demand for money is based on uncertainty. In a certain world, it would be possible to plan income and expenditure so they always coincide and one never has to hold money (Mises 1998, 249–50). Uncertainty, here, is to be understood in the specific sense in which Knight (1964), Mises (1998, 105–18), and Hoppe (2007, 11–13) use it in contrast to risk. It does not concern those aspects of reality that can be dealt with through insurance or cost accounting, which are calculable—what Mises termed class probability. Uncertainty, on the other hand, concerns what Mises called case probability: “Case probability means: We know, with regard to a particular event, some of the factors which determine its outcome; but there are other determining factors about which we know nothing. . . . Case probability is a particular feature of our dealing with problems of human action. Here any reference to frequency is inappropriate, as our statements always deal with unique events which as such—i.e., with regard to the problem in question—are not members of any class” (Mises 1998, 110, 111).

The fundamental motive for holding money is the individual’s felt uncertainty (Rothbard 2009, 264–65), and it is intimately connected with the essential characteristic of money as the most marketable good—marketability being the ease with which a good can be sold in the market at any time at its current market price (Menger 2009, 25; 2007, 248–59). Holding money is the best way to have a reserve for unforeseen contingencies (Hutt 1956, 206, 213), precisely because of its stronger marketability. In this way, we can see how change in the demand for money is ultimately related to change in perceived uncertainty. If people feel more uncertain, they tend to add to their cash balances; if they feel less uncertain, they tend to draw down those balances (Hoppe 2012). We might say that money, due to its ultimate marketability, is comparatively the most certain good.

These considerations show that not only the quantity but also the quality of money is important for its value, and there is a burgeoning literature dealing with this idea (Bagus 2009, 2015; Bagus and Howden 2016; Žukauskas and Hülsmann 2019; Žukauskas 2021). Key to money’s quality is its suitability, as judged by economic actors, for bearing uncertainty. Among the classical functions of money, economists have emphasized its role as a store of value as the function that determines its quality to the individual. We will argue that a good’s marketability is more fundamental because it grounds money’s store-of-value function.

Questions about the quality of money are directly related to the role of close substitutes for money—what Mises calls secondary media of exchange (Mises 1998, 459–61). These are goods and claims that, although not money, have a high degree of marketability. They are very liquid, in standard terminology, because there are large and well-functioning markets for them. Their role is not to serve as media of exchange, but individuals who want to economize on their cash holdings can hold such goods and claims instead—although this is not without hazards. The prices of goods and securities used for this purpose fluctuate, and it may only be possible to realize needed cash at a loss. Holding secondary media thus implies an increase in uncertainty for the holder, since the possibility of a fall in prices and a loss of value is inherent in their nature.

It is our contention in this article that there is a direct causal relation between the demand for secondary media of exchange and the quality of money. Money of low quality, which loses value—that is, declines in purchasing power—imposes a cost on the holders of money.[1] In order to protect their wealth, money holders may not only choose to decrease their holdings of cash in favor of investing in financial assets with some positive yield (Hülsmann 2013, 2016; Žukauskas and Hülsmann 2019; Sieroń 2019, 20) but also increasingly seek to hold secondary media of exchange instead of cash for their liquidity needs. This creates an impression of very liquid markets when, in reality, cash holdings are very low. In a crisis where market actors need to mobilize large cash reserves, the result is an evaporation of liquidity. A sudden increase in the exchange supply of the main secondary media—government bonds, for instance—causes the prices of those media to fall and the liquid reserves held in the market turn out to be much lower than expected.

While coherent and logical, Mises’s presentation of the relationship between money and secondary media of exchange is not always clear. What is needed is a heuristic device that makes evident the interrelations between money, all other goods, and secondary media of exchange. Fortunately, Rothbard’s (2009, 137–42, 756–64) total demand-stock analysis, together with Salerno’s (2010a) model of money prices based on that analysis, provide this device. Žukauskas and Hülsmann (2019) have already used Rothbard’s total demand approach to analyze the relationship between the demand for money and the demand for financial assets, and we will here try to extend this analysis to a general theory of the relation between the demand for money, secondary media of exchange, and all other goods.

Our goal in this article is thus twofold: (1) to examine the Rothbard–Salerno model—that is, the total demand approach—and reconcile it, if possible, to a clear statement of the cash balance demand for money; (2) to apply the model to examine the interrelations between demand for money and demand for secondary media of exchange and thereby get a fuller understanding of the role of the quality of money.

Rothbard’s Equation and the Model of Money Prices

Since money is not consumed and renders its services simply by being held, if we want to investigate the determinants of the value of money—the money relation—the best approach is total demand-stock analysis. Rothbard adopted this approach from the work of Philip Wicksteed (1910) and applied it to monetary theory. The total demand for a given good is the exchange demand by the nonpossessors plus the demand to hold, or reservation demand, by possessors (Rothbard 2009, 137). Total demand analysis is especially appropriate when only a fraction of a good’s stock is exchanged during a market period. This is the case with housing and land, where annual production is minuscule relative to total supply—and the same is true of money (Cannan 1921, 453).

As long as we consider only total demand, this approach appears unproblematic to advocates of the Misesian pure cash balance approach. At any given time, all monetary units are held by someone: each person holds a cash balance corresponding to his personal judgment (Newman 2025) such that the utility of his marginal monetary unit is higher than that of the good or service just below it on his value scale. “Every piece of money is owned by one of the members of the market economy. The transfer of money from the control of one actor into that of another is temporally immediate and continuous. There is no fraction of time in between in which the money is not a part of an individual’s or a firm’s cash holding, but just in ‘circulation.’ . . . Nobody ever keeps more money than he wants to have as cash holding” (Mises 1998, 399, 401).

That money is transferred from actor to actor does not contradict the pure cash balance approach—in fact, it is a necessary implication of Mises’s theory of money. The demand for money depends on the purchasing power (or, in the older terminology, the objective exchange value) of money—that is, the array of money prices. Knowledge of past prices allows market actors to form expectations about the future purchasing power of money (PPM), and these expectations determine the value of money to them and its place on their value scales (Hülsmann 2012, 10). The relative positions of money and of all other goods on individual value scales in turn determine how much money each person keeps and how many units of other goods he acquires at given prices. Thus, the demand for money is fully integrated with the rest of price theory. In the words of Salerno (2010a, 132), Mises demonstrated “that there is no theory of money properly speaking, but only a theory of money prices.”

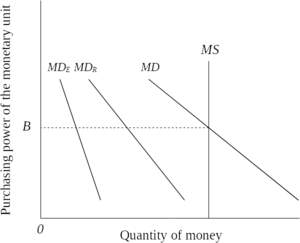

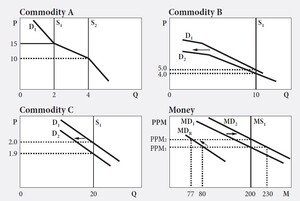

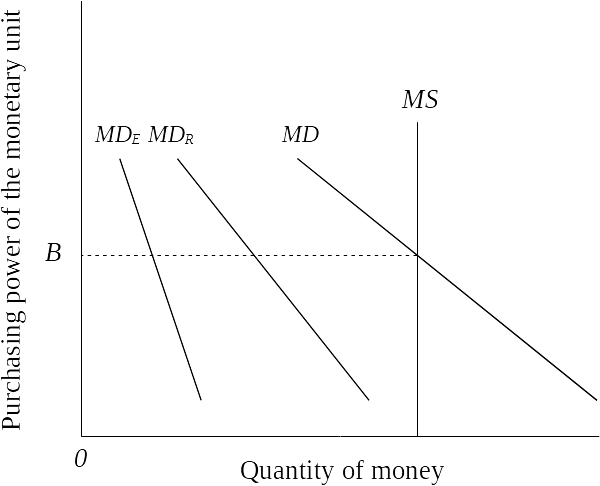

Rothbard’s disaggregation of the demand for money into exchange demand and reservation demand shows this integration. The exchange demand for money is exercised by the sellers of all other goods who wish to acquire money, and the reservation demand by those who already own money. The supply of all particular goods and services sold against money is thus a partial exchange demand for money (Rothbard 2009, 756). By adding exchange demand to reservation demand, we arrive at total demand for money, as shown in figure 1.[2]

Expanding on Rothbard’s framework, Salerno (2010a, 133–34) has worked out an equation (“Rothbard’s equation”) that describes equilibrium in all markets as well as the market for cash balances. The general form is

MS=MDE+MDR=MD,

where

MS=Money supply

MD=Total demand for money

MDE=Exchange demand for money

MDR=Reservation demand for money

Exchange demand can furthermore be understood as

MDE=(P1×Q1)+(P2×Q2)+…+(PN×QN),

where

P1…N=Market clearing price of nonmonetary commodities 1 to N

Q1…N=Market clearing quantities of nonmonetary commodities 1 to N

Exchange demand for money can, following equation (2), be disaggregated into all the specific markets for nonmonetary goods. The supply of these goods in fact constitutes the exchange demand for money, just as the exchange supply of money constitutes the exchange demand for the goods in each specific market for nonmonetary goods. Salerno goes on to show this in his model, which demonstrates the interaction of the prices of goods, PPM, and the demand for money.

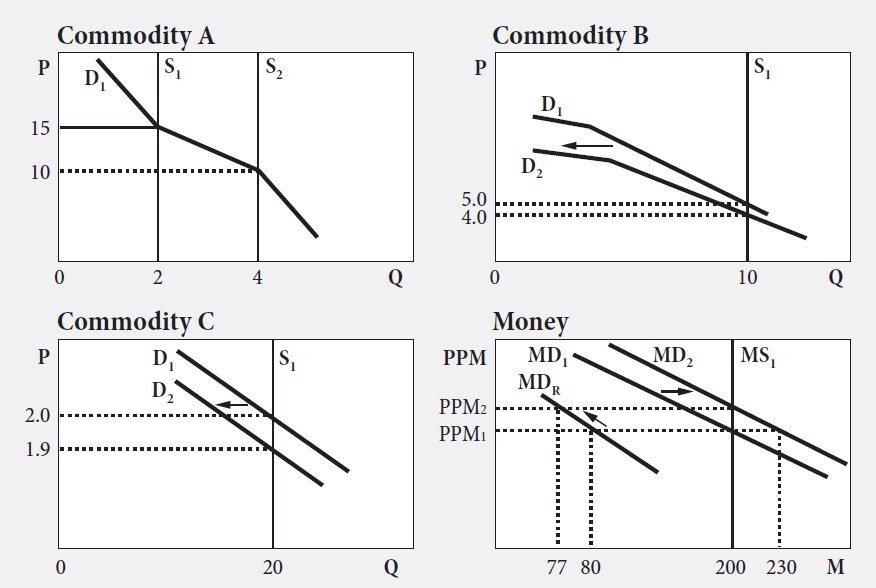

In this model (figure 2), the economy consists of the markets for three commodities—A, B, and C—and the market for cash balances, where reservation demand and total demand for money are depicted. The exchange demand for money is determined by the curves S1 and D1 in the three diagrams (the role of the movement from S1 and D1 to S2 and D2 does not concern us here), which are derived from the supply and demand schedules for the nonmonetary goods in the economy. The reservation demand is simultaneously determined in the market for cash balances. Money prices and the purchasing power of money—the inverse of the prices of goods—are here intimately connected, and the demand for cash balances is determined in the same process that establishes equilibrium in all other markets.

While the steps taken in disaggregating the demand for money are all logical, it might appear that we have now abandoned the Misesian cash balance approach to money. After all, even if exchange demand is not exactly the same as circulating money, is it not at least akin to transaction demand for money? In figure 2, it appears as if only 80 monetary units out of 200 are held in cash balances, while the rest are exchanged for nonmonetary goods. If we take the cash balance approach seriously, the total stock of money should always be held in someone’s cash balance. Yet if we accept Salerno’s model as a depiction of the total demand approach, the exchange demand for money will appear worryingly detached from the demand to hold. Both Salerno and Rothbard insist that they have not abandoned the cash balance approach, so how are we to interpret their elaboration of monetary theory?

Rothbard (2009, 757; italics in original) himself suggests the solution to our problem when he says that “the exchange demand [for money] is [the market actor’s] pre-income demand.” He does not elaborate on this statement, except when he refers to chapter 6 of Man, Economy, and State, where he first introduced the concepts of pre- and post-income demand.

To fully understand the import of the Rothbard–Salerno theory, we therefore need to return to chapter 6 and excavate these concepts. But a new challenge confronts us here: Rothbard (2009, 410–20), in chapter 6, is concerned exclusively with the time market and introduces the distinction between pre- and post-income demand as a way of understanding the demand for present goods. Pre-income demand is the individual’s demand for present goods (money) at the outset, before he sells his services as a laborer or the services of his land and other producer goods in exchange for money. Post-income demand is the individual’s demand for present goods (money) after he has sold his services. Since Rothbard is exclusively analyzing the time market here, post-income demand for money is demand for consumer loans—that is, for present money against future money (416–18). Market actors in a post-income position are also likely to be suppliers of present goods (money) in exchange for future goods—that is, they will invest some of their cash balance in productive assets.

Now, this exposition of pre- and post-income positions may seem paradoxical, since it makes the same persons demanders and suppliers of present goods. Rothbard addresses this apparent paradox head on (2009, 411; italics in original):

How can a laborer or a landowner be a demander of present goods, and then turn around and be a supplier of present goods for investment? This seems to be particularly puzzling since we have stated above that one cannot be a demander and a supplier of present goods at the same time, that one’s time-preference schedule may put one in one camp or the other, but not in both. The solution to this puzzle is that the two acts are not performed at the same time, even though both are performed to the same extent in their turn in the endless round of the evenly rotating economy.

In the real world, most people are continually shifting between pre-income and post-income positions—between earning an income and spending it—and therefore continually shifting between being demanders of present goods and demanders of future goods. Their positions at any given time are determined by the size of their cash holdings and their value judgments about future versus present goods. A person will continue to supply present money in the time market until the value of the marginal unit of any present good outranks the value of the marginal unit of future money he expects to receive. Similarly, he will draw on his cash balance to purchase consumption goods until the value of the marginal monetary unit he would have to give up for one more unit of any consumer good outranks the value of one more of any consumer good. “This is the law of consumer action in a market economy.” Every individual “will spend money on each particular good until the marginal utility of adding a unit of the good ceases to be greater than the marginal utility that its money price on the market has for him” (Rothbard 2009, 281).

We should now be in a position to expand on Rothbard’s somewhat elliptical identification of exchange demand for money with pre-income demand. Since Rothbard uses the concept in the context of the time market, we simply need to broaden the scope of the definition to all markets where money is exchanged. Pre-income demand for money thus becomes the demand for money exercised by all suppliers of future and present goods and services, claims, and all other conceivable assets. What Rothbard identified as post-income demand for money in the form of consumer loans is thus, in this broader view, really a particular form of pre-income demand. Exchange, or pre-income, demand for money is demand for increased cash balances, and it is fully determined by the place of the marginal monetary unit in relation to all other goods on each person’s value scale. It is, assuming no payment is made in kind, the same as a person’s demand for income.

A person in a post-income position is not looking to add to his cash balance, since he values what he would have to give up higher than the marginal monetary unit or units he could acquire by giving it up. He may simply be in a state of rest, abstaining from all market action, since no exchange could render him more satisfied at the moment (Mises 1998, 245). It might also be that people in a post-income position wish to draw down their cash holdings, either through consumption or by investing in future goods. In this case, they become suppliers of money in all markets, including the market for consumer loans.

Analytically, we must therefore distinguish two periods in the market. In period 1, any given person is either in a pre- or post-income position. In period 2, that same person is necessarily in the other position.[3] If, in period 1, a person exercises exchange demand for money, in period 2 he will be either in a state of rest or drawing down his cash balance in order to invest or consume. Every person is continually changing his position, and the length of the period is individual to each person, since it depends on individual plans and desires. Objective factors—such as whether laborers are paid weekly or monthly—play a role only insofar as they influence individual decisions. The effective exchange demand for money by some individuals must necessarily be met by an equal exchange supply of money from others—that is, for every monetary unit added to someone’s cash balance, someone else must draw down his cash balance proportionally. In this way, the flow of money through the economy is simply the result of the continually changing valuation of money by acting individuals (Salerno 2010a, 147).

Hopefully, this clears up the distinction between exchange demand and reservation demand for money. At every moment, the pre-income demanders hold as much money as they want to, given present opportunities for increasing their cash balance, but they are in the process of increasing their cash holdings. Similarly, at every moment, the post-income demanders are satisfied with their present holdings of money, given present opportunities for decreasing their holding, but they are in the process of drawing down their cash balances. Even if, at the end of a market period, not everyone who wanted to draw down their cash balances did so, this does not mean that there is a disequilibrium or excess supply of money. It means, rather, that the post-income suppliers of money expect to be able to make better trades during the next market period. Similarly, if pre-income demanders exhaust all possibilities for increasing their money holdings, it is because they find it too costly.

At the end of every market period,[4] then, every monetary unit is in someone’s cash holding, whether he be a pre-income or post-income demander of money.

The reservation demand for money is not an arbitrary remnant left over after demand for other goods has been satisfied but is itself determined by the position of the marginal monetary unit versus other goods on the value scale. In the normal course of life, market actors will again and again be in a position where they would rather acquire more money than delve deeper into their cash reserves.

Interestingly, far from being a purely Austrian theory, this way of understanding the cash balance approach may have been what Marshall (1923, 44) was working toward when he made the national aggregate demand for money dependent on both the nation’s income and assets. We can now see that income, rather than determining the demand for money, is simply exchange demand for money for some people and exchange supply for others. Similarly, a person’s allocation of income between consumption, investment, and his cash balance determines the full range of property he owns, including money in his cash balance.

By spelling out the relationship between pre-income and exchange demand for money, we see that the Rothbard–Salerno model is a fuller description of the Misesian pure cash balance approach to the demand for money. Our next task is to examine the demand for secondary media of exchange in light of these considerations.

The Quality of Money and Secondary Media of Exchange

For anything to be a good, it must have some quality that the acting individual thinks will help him achieve some end. If a thing has, or is believed to have, no such quality, it will not be considered an economic good by anyone. The same is true of money, but in modern economics, discussions concerning the quality of money have been virtually absent. Mises and Rothbard only treated it indirectly, without explicitly naming it. Recently, Philipp Bagus has made the concept of the quality of money explicit in a series of articles dealing with the topic (Bagus 2009, 2015; Bagus and Howden 2016). As Bagus (2009, 23) defines it, the quality of money is its capacity, as perceived by acting individuals, to fulfill its main functions—namely, a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

There is much value in the classical formulation of the functions of money, but it overlooks or sidelines what we consider its main function as outlined above: holding money gives the acting individual ready access to a fund of purchasing power and thereby alleviates his felt uncertainty. The two main functions of money that Bagus considers in relation to its quality—medium of exchange and store of wealth—are, in this view, so tightly connected that they are practically indistinguishable. It is only because a thing is a commonly used medium of exchange that it can alleviate felt uncertainty, and it is only because it is a store of wealth that it can be used as a medium of exchange (Bagus 2009, 33n). Store of wealth, here, simply means stable or falling prices in terms of the monetary commodity—and what is this but an aspect of the marketability that allows the commodity to be a medium of exchange? Understood in this sense, Mises (1998, 398) is perfectly correct when he says, “Money is the thing which serves as the generally accepted and commonly used medium of exchange. This is its only function. All the other functions which people ascribe to money are merely particular aspects of its primary and sole function, that of a medium of exchange.”

To avoid terminological confusion, it would have been preferable if Mises had used another word besides function in this passage, but our interpretation of it is clear: people demand money to hold to alleviate felt uncertainty, and the reason they demand money and not some other thing is that it is the most commonly used medium of exchange and therefore best suited for this role.

We can group the main factors affecting the quality of money under two headings: those factors that affect its marketability and those that affect the purchasing power of the monetary unit. But the import of all factors is ultimately how they influence money in its function of alleviating felt uncertainty.

Marketability is the sine qua non of a good’s acquiring and retaining monetary status. The classic elaborations of the qualities that make a good more marketable fall under this heading. The most important quality for the monetary commodity is widespread nonmonetary demand, both for the commodity’s emergence as money and for its continued status as such (Bagus 2009, 31; Hülsmann 2003, 39). Other qualities—divisibility, portability, fungibility, recognizability—influence a commodity’s marketability. It is conceivable that even once one commodity is established as money, another could displace it if it were more marketable. The lack of nonmonetary demand for modern paper money, for instance, makes this kind of money inferior to commodity money such as gold (Hülsmann 2003, 39).

The purchasing power of money—or rather, expected changes in PPM—also influence the quality of money. On the free market, money production would be constrained by the costs of production, and more money would only be produced if it were profitable. Inflation, properly understood, would be impossible (Mousten Hansen and Newman 2022). With modern paper money, by contrast, inflation becomes possible. Money production is only constrained by the institutions in charge of monetary policy and the ideas guiding them. Factors such as the independence of the central bank, the fiscal needs of the state, and the monetary philosophy guiding the directors of the central bank become important here. The status of money in the broader sense is also important in determining the quality of money—that is, it matters not only how big the fiduciary issue is but also what kind of assets the banks own. The bigger the fiduciary issue, the lower the quality of money. The less liquid the assets, the lower the quality of money. (On all this, see Bagus 2009, 34–39.)

In general, money of stable or increasing purchasing power is high-quality money, and money of falling purchasing power is low-quality money. A monetary good increasing in purchasing power over time is better suited to its purpose than one of falling or even stable purchasing power.

Changes in the Quality of Money

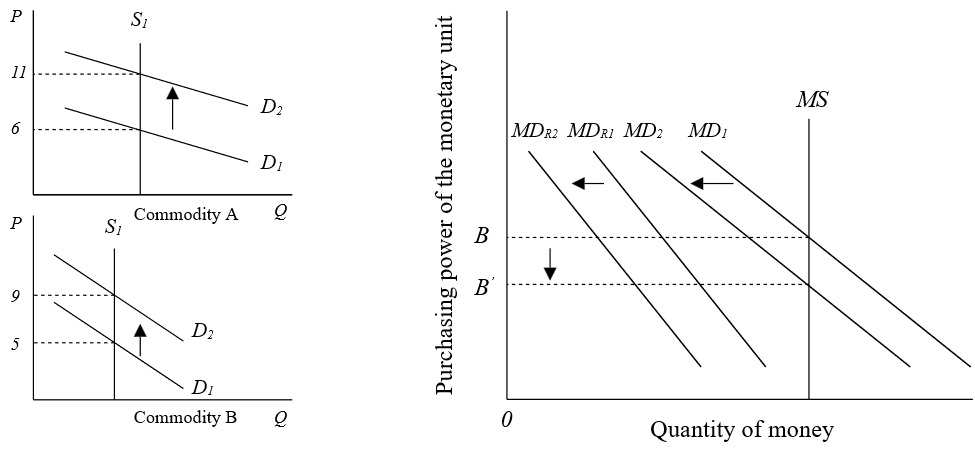

Changes in the quality of money directly affect the demand for money. In the model presented above, we can isolate the change on the side of reservation demand: if the quality of money falls, so will the reservation demand for money. The curve MDR falls as people draw down their cash balances. At the same time, the demand schedule for some goods and services rises as more money is spent in these markets. The result is a fall in the purchasing power of money and a new equilibrium situation where money prices are higher, PPM is lower, and MDR is lower.

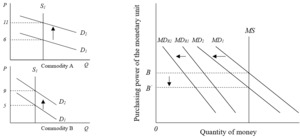

Figure 3 shows this change. We depict a market with only two nonmonetary goods and a fixed stock of money. A fall in the perceived quality of money induces a fall in the reservation demand for money from MDR1 to MDR2. This fall means that the holders of money will now spend more on nonmonetary goods, increasing the exchange supply of money. This leads to higher prices and a lower PPM, until a new equilibrium is reached. This is depicted by the markets for commodities A and B. Here, the demand curves rise from D1 to D2 while the stock of the good S1 remains unchanged. The result is higher prices for commodities A and B, a fall in PPM, and, in general, a lower total demand for money schedule.

The real money supply has fallen because the fixed stock is now worth less. While it is possible to draw the MDR curves in such a way that reservation demand is larger in nominal terms at the lower PPM, it would still be smaller in real terms. This geometrical possibility, however, should not confuse us: since prices of goods are now higher and the supply of nonmonetary goods is unchanged, the exchange demand for money must have increased in nominal terms.

The figure should not be taken to mean that only the prices of a few commodities are affected by the fall in the quality of money. Looking beyond our simple model, we can see that as the suppliers of A and B receive higher incomes, they too will increase their spending, in turn bidding up prices. This goes on throughout the economy, as incomes increase and prices are bid up, until a new equilibrium emerges. The process mirrors what happens when a new supply of money enters the economy, as described by Mises (1953, 208–11) and known to modern economists as the Cantillon effect (Sieroń 2019).

However, there is one important difference from the case of new money entering the economy which leads us to modify the above exposition. When the quality of money falls, it is possible that the result will be a general rise in prices as just depicted, but it is far more probable that the holders of money will seek substitutes for their now lower-quality money. Instead of simply increasing spending generally, market actors who perceive their money to be lower quality are likely to exchange their money for what Mises terms secondary media of exchange.

Secondary media of exchange (Mises 1998, 459–61), or quasi money (Rothbard 2009, 826–27), are commodities and claims that can partly fulfill the function of money for the holder. They are very liquid goods—or have a high degree of secondary marketability, in Mises’s terminology—and can therefore partly serve the same function as money for the acting individual—that is, they can substitute for cash holding.

It is important to stress that secondary media of exchange are not primarily used in exchange but are substitutes for holding cash—not substitutes for using cash in exchange. If secondary media of high quality are available, the holder of money can reduce the cost of holding cash by keeping part of his wealth in the form of secondary media of exchange. As in the case of money, what makes for a good secondary medium of exchange is determined by its marketability and expected changes in price. In distinction from money, it is only the liquidity of the market, in terms of money, and the money price of the medium of exchange and its evolution that determine the quality of the secondary medium of exchange. For instance, we can consider gold a secondary medium of exchange in the modern economy. What makes it a good secondary medium of exchange is that it is very liquid and can always be readily sold against money with little spread between bid and ask prices (Bagus 2009, 32–33) and that its price is generally expected to rise in terms of money—that is, the purchasing power “stored” in a quantity of gold is expected to remain stable or rise.

The demand for secondary media of exchange can be modeled in the same way as the demand for money. It is principally a demand to hold in order to economize on one’s cash balance, and the same kind of total demand analysis can be used to model it. Žukauskas and Hülsmann (2019) pioneered this approach in their investigation of the relationship between the quality of money and the demand for financial assets. This approach can be generalized to hold for all secondary media of exchange.

Figure 4 shows the market for gold as a secondary medium of exchange. It is very similar to figure 1 since the demand for secondary media of exchange is motivated by the same considerations as the demand for money. The bulk of the demand is reservation demand, but there is also substantial exchange demand since there is a very liquid market for gold, ensuring up-to-date price information for the holders of gold and the possibility of speedily and efficiently liquidating their holdings. Total demand D is the sum of exchange demand DE and reservation demand DR.

When the quality of money falls, for whatever reason, it is probable that the result will be a rise in the demand for secondary media of exchange rather than a general rise in prices. Income-generating assets such as bonds and marketable commodities with money-like qualities such as gold will rise in demand and price before other goods. As the reservation demand for money falls and shifts left, the reservation demand for secondary media of exchange rises and shifts right.

Figure 5 combines figure 3 and figure 4. As the quality of money falls, reservation demand for money falls and the reservation demand for secondary media of exchange (here, gold) rises. Since the MD curve falls and the overall PPM falls, it might appear that there is a general rise in prices, but most of the action takes place in the secondary media of exchange markets. The prices of other goods rise only later, if at all.

The diagram shows the relationship between the demand for money and the demand for gold, a widely demanded secondary medium of exchange. It is a straightforward relationship of substitutability. While we cannot speak simply of a changing price of holding money, we can speak of changing costs of holding money. As the quality of money falls (or rises), the costs of holding it rises (or falls) and demand shifts to (or away from) its close substitute—gold, in this case. The diagram shows how a fall in reservation demand for money leads to increased demand for gold. Not depicted is the temporary rise in exchange demand for gold as more nonpossessors of gold enter the gold market. As the price of gold rises to its new equilibrium position, the exchange demand is likely to fall back toward its earlier position. The result is that more people now hold a greater proportion of their wealth in the form of gold and less in the form of money.

However, integrating secondary media of exchange into the model shows more than this relation of substitutability. Since the main effect of a falling quality of money is on the side of reservation demand for money and secondary media of exchange, a regime of deteriorating quality of money is not incompatible with stable or only slowly rising prices. It is even possible that the very fact of falling quality may induce higher exchange demand for money in the short term—people may wish to acquire more money in order to buy appreciating assets before it’s too late. Since the exchange demand for money in the form of supply of present goods and labor services likely cannot increase much, if at all, the increased exchange demand for money is likely to take the form of increased demand for money loans. Falling quality of money thus engenders greater willingness to go into debt, on the part of both consumers and producers (see Hülsmann 2016).

A regime of low-quality or falling-quality money is thus characterized by low and falling reservation demand for money, since people will not wish to hold poor-quality money for long, and relatively high exchange demand for money, since people will want to acquire money to invest in income-generating and appreciating assets. The increased exchange demand for money will mainly take the form of an increased demand for money loans, since borrowing money to invest in liquid assets is the only short-term way of increasing one’s demand for money. A lower quality of money can thus result in an increased dominance of market relations—especially financial market relations—in everyday life. Individuals will, if possible, supply more labor services to generate income for investment, but the principal consequence is that the demand for loans will increase as market actors speculate on further falls in the quality of money and appreciation of secondary media of exchange and go into debt to preserve their wealth.

The quality of money is thus a crucial but so far completely neglected component in understanding the phenomenon known as financialization (Krippner 2012; Palley 2013). The “growing importance of financial activities as a source of profits in the economy” (Krippner 2012, 27) characteristic of financialization is not simply a result of an accidental change in ideology, as many scholars suggest (e.g., Palley 2013, 1), but rests on a deformation of the monetary order of society which has led—among other consequences—to a continuing fall in the quality of money.[5]

Estimating the Quality of Money and Quasi Money

If we are correct in our explanation of the relationship between the quality of money, the demand for money, and the demand for secondary media of exchange, then the same factors that influence the quality of money should influence the quality of secondary media of exchange. Relative demand for these different asset classes would then be explained by changes in their monetary quality, the quality of money, or both.

But since the quality of money is a question of the acting individuals’ subjective value judgments, finding objective measures of monetary quality is inherently problematic. At best, we can establish some objective phenomena that are likely to enter into individual value judgments and thereby affect the quality of money. One way of estimating the quality of money is to construct an index (Žukauskas 2021) weighing the different indicators of quality suggested by Bagus.

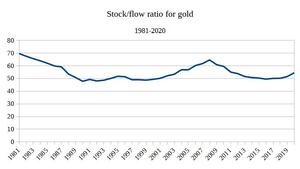

A measure of monetary quality that is becoming increasingly popular is the so-called stock-to-flow ratio, which first gained prominence because of the work of Saifedean Ammous (2018). The ratio compares the growth rate of the money supply and of secondary media of exchange to their total stock. A growth rate of 2 percent, for instance, is equivalent to a stock-to-flow ratio of 50. In other words, what we are really looking at is just the growth rate of money, but the transformation into the stock-to-flow ratio makes variations in the growth rate more prominent.[6] The reasoning behind the measure is that the “hardness,” or quality, of money is determined by the relation between the stock of money in existence and the flow of newly produced money. The less money that is currently being produced relative to the stock, the “harder” the money—that is, the higher its quality. A higher stock-to-flow ratio is thus always better than a lower one. While this reasoning appears plausible, it is fundamentally flawed.

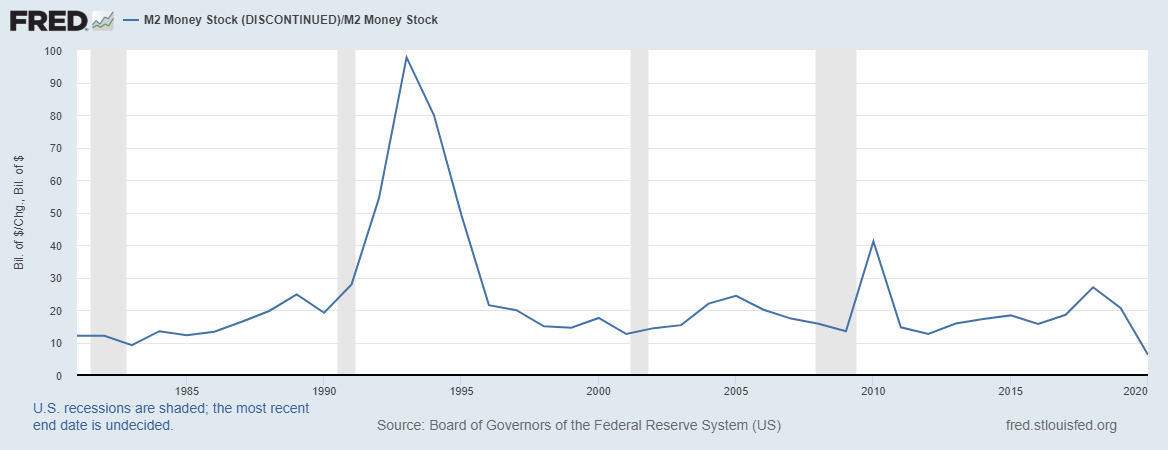

If we look at figure 6, which depicts the stock-to-flow ratio of the US dollar supply as measured by M2 from 1981 to 2020, it seems to suggest that the dollar is a low-quality money. The ratio is low and fluctuates widely. It does not, however, appear to trend either downward or upward, suggesting no change in the quality of dollars.

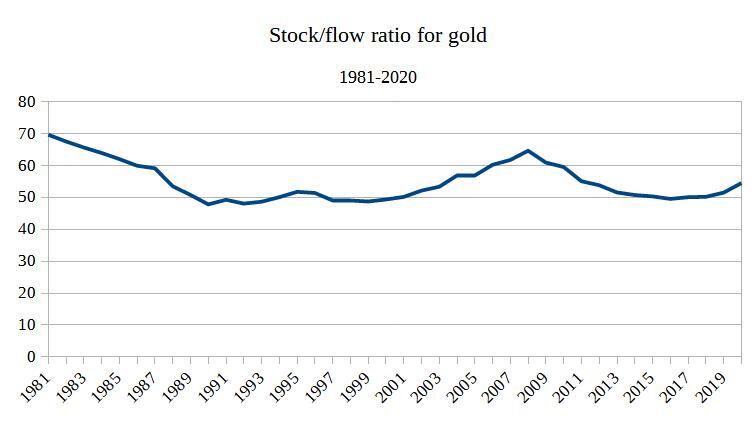

At the same time, the monetary quality of gold is clearly higher than the dollar’s as measured by the stock-to-flow ratio (figure 7). The ratio has been stable over the period from 1981 to 2020 in the interval from 50 to 60, and if we extend the time series further back, the ratio does not change much. But again, there is no change in trend, making it hard to conclude on this basis that the quality of dollars fell or that of gold rose during this period. If we only look at the stock-to-flow ratio, we cannot explain the rising dollar price of gold as the result of the falling quality of money.

The stock-to-flow ratio is especially used as an argument for the high quality of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. Since there is a hard ceiling of 21 million on the total stock that will ever be produced, bitcoin, it is claimed, is even harder—that is, of higher quality—than gold. It has even been claimed that the ratio is a predictor of the future evolution of the price of bitcoin. Yet this focus on the ratio of production to stock is arguably misplaced—what matters is not how much is produced but the institutions governing money production and the way money is produced (Mousten Hansen and Newman 2022; Salerno and Hansen 2022).

The hard ceiling on the stock of bitcoin means that there is no danger and no perception of danger of bitcoin supply inflation. It is therefore an important datum in assessing the quality of bitcoin. However, the stock-to-flow ratio of bitcoin is, by itself, arguably completely irrelevant. Since the production schedule is certain a hundred years in advance, it is already taken into account in the present valuation by holders of bitcoin insofar as it is an important feature to them—in other words, it is already priced in.

The monetary quality of gold is also not simply a question of its rate of current production. Gold production is a market phenomenon, and it expands and contracts according to the data of the market. It is very unlikely that large “external” supply shocks will occur—for example, in the form of huge new gold discoveries. Indeed, the large gold discoveries of the nineteenth century arguably did not dislocate gold markets and monetary systems. This is because gold production is entirely endogenous to the market, and gold flows into money (or quasi money) holdings when demand for it increases and out when demand falls (Mousten Hansen and Newman 2022; White 1999, chap. 2).

What the stock-to-flow ratio of the dollar reveals is not that the dollar is a low-quality money—although it arguably is that. Rather, it shows that the production of fiat money, such as the dollar, is not endogenous to the market in the same way that the production of gold or another commodity money is but depends on the demand for loans and on fluctuations in the financial sector—hence the sudden spikes in the ratio during times of crisis. Since the demand for loans is not independent of the rate of interest at which they can be contracted, and since commercial banks and central banks can lower the rate if they so desire, the production of money becomes a question of central bank policy. This power of the central bank is one key reason for the low quality of modern fiat money, which the stock-to-flow ratio only hints at.

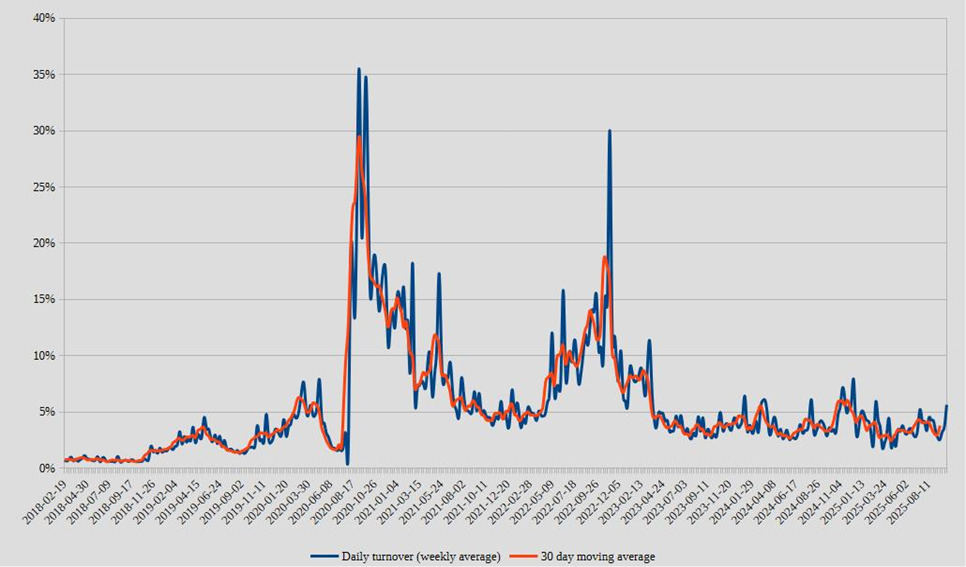

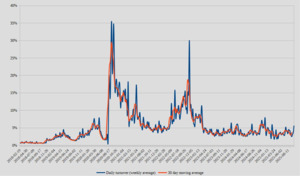

This does not mean that bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are not held as secondary media of exchange, nor that they are not endogenous to the market. But the price volatility of cryptocurrencies—despite appreciation over the long term—would suggest that they are still not as suitable for monetary purposes as, for example, gold. That there is a large speculative element in bitcoin demand is suggested by the ratio of daily turnover to total stock. This ratio can be considered a proxy for the relation between exchange demand and reservation demand (see figure 8). The larger the proportion of reservation demand relative to exchange demand, the lower this ratio will be. Bitcoin’s ratio has fluctuated widely in recent years, from around 2 percent to peaks above 30 percent and periods of sustained turnover over 10 percent. This indicates high inflows and outflows of capital in the bitcoin market, which in turn suggests a high degree of speculative activity. By comparison, daily turnover in the gold market is roughly 1.5 percent of the market value of the stock of gold and is not subject to the same variations.

This is not meant to suggest that there is no future for bitcoin as a quasi money, nor to deny that there is some demand for bitcoin to fill this role. It does appear, however, that gold is still the better secondary medium of exchange.

Conclusion

In this article we have tried to clarify and build on Rothbard’s approach to explaining demand for money, which, as we have seen, follows the Misesian pure cash balance approach to the demand for money and elucidates the relationship between PPM and money prices while leaving the unitary explanation of the demand for money intact.

We have tried to extend the model further by showing how we can integrate close substitutes for money—Mises’s secondary media of exchange. By doing so, it has become clear that the falling quality of money does not necessarily lead to a general increase of all prices but primarily affects the markets for close substitutes for money—namely, comparatively safe financial assets, liquid commodities such as gold, and other money-like assets.

This is not meant to imply that the quality of money only concerns inflation—indeed, price inflation is as much a consequence as a cause of declines in the quality of money.

We need not go into the problem presented by the vertical axis of figure 1. Strictly speaking, we cannot determine PPM quantitatively at all. We can define the purchasing power of money as the inverse of the price level, but this does little to help us since price level here is not some objectively determined aggregate but the whole array of prices. A virtual infinity of different units would need to be presented on the vertical axis for it to be accurate.

The periods of time are not objective but subjective to each individual. It may be, as a matter of history, that the periods tend to synchronize across individuals, but this is by no means certain.

To be precise, money is allocated according to demand after each individual exchange. Since exchanges are always immediate and not extended through time, money is always allocated according to demand.

While changes in the quality of money are hard to estimate and express quantitatively, recent research (Žukauskas 2021) has attempted to construct an index measuring the quality of the euro. This index suggests a significant fall in the quality of the euro over the first twenty years of its existence.

An anonymous referee urged me to clarify the argument of the stock-to-flow model. Žukauskas (2021, 139) also uses the growth rates of the money supply to estimate the quality of money. I thank the same referee for pointing this out to me.

_and_the_deman.png)

_and_the_deman.png)