Sequestered capital is capital that is hidden or unseen by the market. R&D is often sequestered capital. New goods in production can be sequestered capital. Sequestered capital is special because it doesn’t inform price signals. In a series of papers, McClure and Thomas use the idea of sequestered capital to explain market anomalies. In [one published] paper they look at sequestered capital and the Dutch Tulipmania. . . . In a working paper (with Steve Horwitz) they look at sequestered capital and closed end funds.

—Alex Tabarrok, “Sequestered Capital,” Marginal Revolution

This article draws attention to a long unknown, and still largely unconsidered, lacuna in capital structure theory. The sequestered capital approach to understanding research and development (R&D) is a corollary of Friedrich Hayek’s (1945, 9) thesis that the free-market price system is a “marvel” because it economizes on the knowledge that market participants need in order to coordinate their plans in “the right direction.” The corollary is this: because market prices do not yet exist for the potential future products that are being researched and developed by entrepreneurs who are sequestering their preparations, that marvelous coordination of lateral competitors’ plans cannot take place until the new goods begin to be launched on the open market as priced products. The absence of prices on potential products being researched and developed in anticipation of expected future launch, and the absence of profit and loss feedback prior to new-product launches, distinguishes the circulating capital in the R&D process from the circulating capital in traditional stages of production focused upon by Austrian economists.

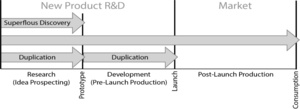

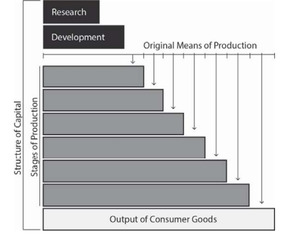

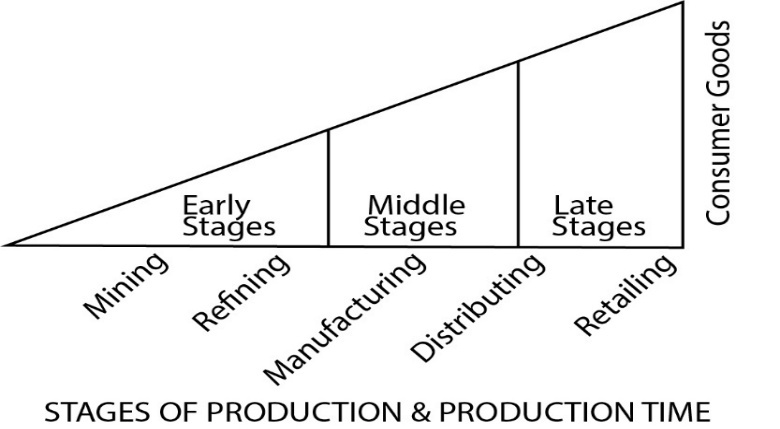

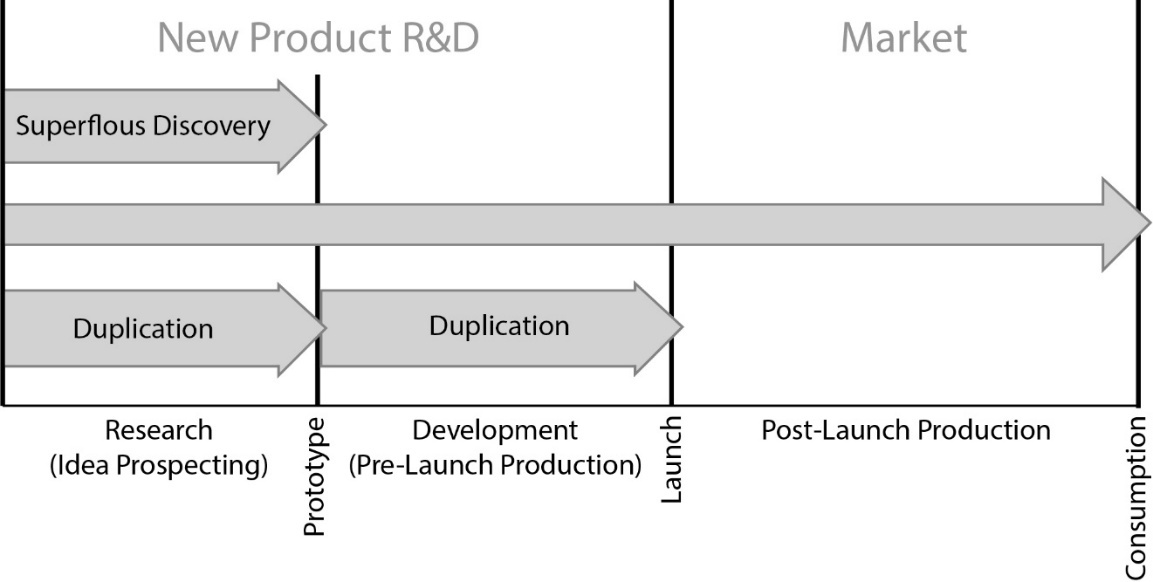

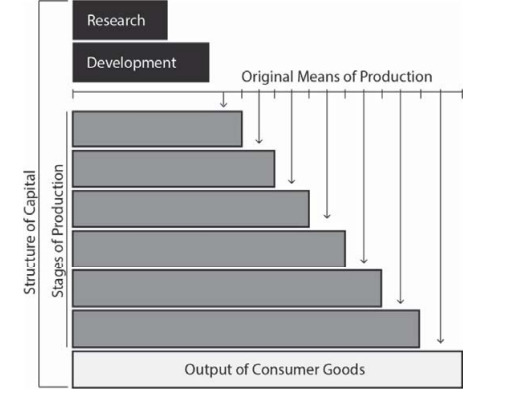

In a 2018 article in the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics (QJAE), we broke R&D into three stages: “1) a research stage that discovers potential products; 2) a development stage to turn the potential products into working prototypes and productize them; and 3) a final stage to develop (produce) pre-launch inventories” (McClure and Thomas 2018b, 21). The directional arrows in figure 1 represent flows of circulating capital moving through time. As shown in the figure, superfluous discovery can occur in the research stage (and historically it has[1]), and duplicative overinvestment can occur in both the research and the development stages.

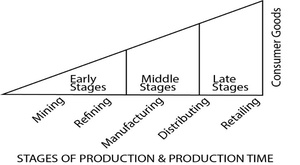

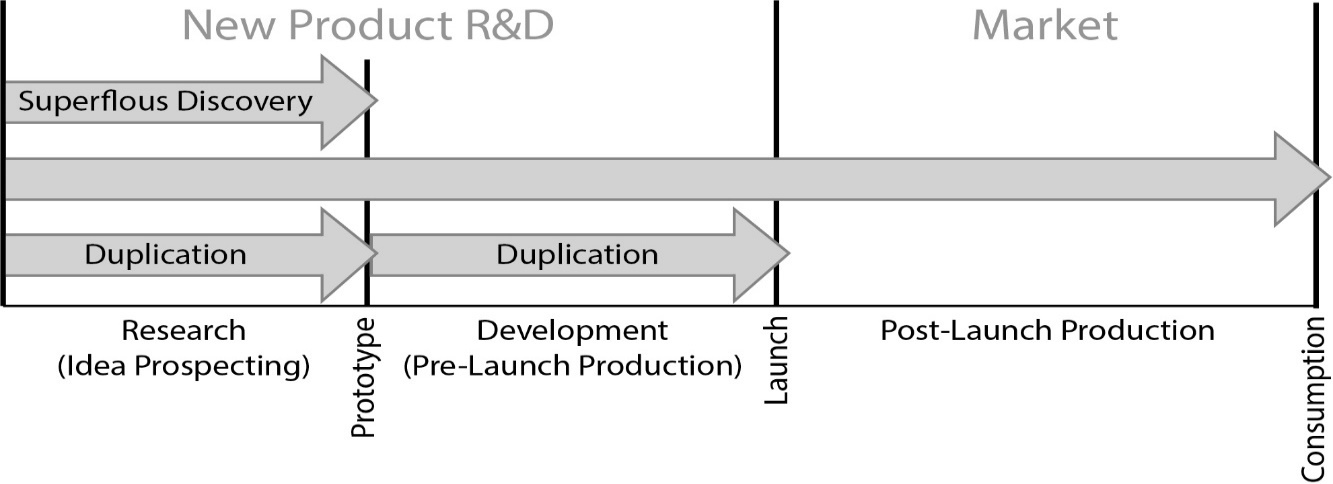

Figure 1 can be connected to Roger Garrison’s (2001, 47) rendition of the structure of capital by placing R&D as the earliest component of the capital structure instead of “mining,” as Garrison did in his Hayekian triangle in figure 2.[2] In a subsequently produced PowerPoint slide on capital-based macroeconomics, Garrison (2011) illustrated the earliest component as “product development” rather than mining. Had Garrison revisited his book’s discussion of Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) with “product development” and creative destruction in mind rather than “mining,” he might have connected his independent analyses of innovation and ABCT.

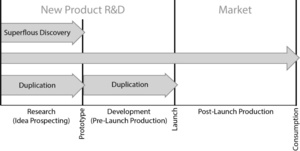

David Thomas and I made such a connection in our 2018 QJAE article, hypothesizing that excessive credit expansion would “bloat” into unsustainable sizes the directional arrows for “superfluous discovery” and “duplication” in figure 1, as shown in figure 3.

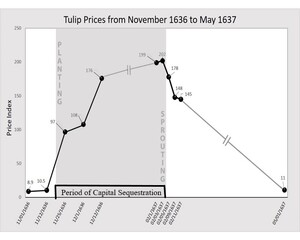

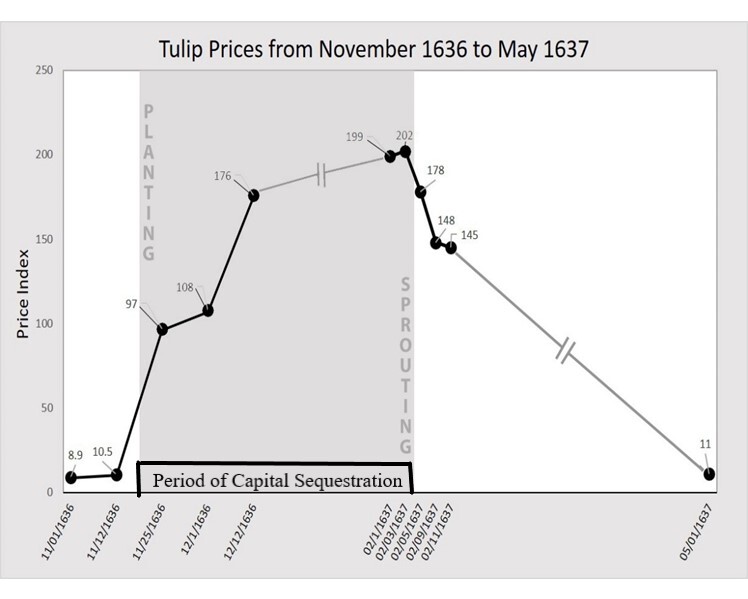

Prior to our QJAE publication, in a 2017 article in the Financial History Review, David Thomas and I had provided a robust demonstration that shed new light on the Dutch tulipmania of 1636–37. In McClure and Thomas (2017), building upon Doug French’s (2006) investigation of Dutch credit conditions during the tulipmania decade, we examined tulipmania through the lens of sequestered capital. Our hypothesis was that the 1636 boom in bulb promissory note prices commenced when unknown quantities of bulbs were planted (literally sequestering bulb development underground) and collapsed when the sprouts emerged in the spring (signaling to promissory-note traders the quantity of bulbs to expect at harvest). We found that the boom and bust timings indeed line up with the sequestered capital hypothesis, as illustrated in figure 4.

Furthermore, the first place tulip promissory note prices collapsed was in the city of Haarlem, where the temperature profile is most suitable for early sprouting. Based on the evidence, we concluded that “the odds that the timings of the Tulipmania boom and bust occurred purely by chance, rather than because the bulbs were sequestered beneath the ground, is below 1.4 per cent” (McClure and Thomas 2017, 140).

Frequently Published, but Still Infrequently Considered

By the end of 2018, David Thomas and I were ecstatic about the progress we had made. Not only had we published two papers on the sequestered capital lacuna in Austrian capital theory, but we had also, on the basis of our approach, published the first-ever explanation of the timings of the tulipmania boom and bust. Fast-forward to 2025, when evidence indicates that the sequestered capital lacuna remains generally overlooked by Austrian scholars, despite the decisions of editors and referees to enthusiastically accept seven articles for publication on the subject since 2016. Aware of this oversight and seeing an opportunity to bring it to the attention of Austrian scholars at the 2025 Austrian Economic Research Conference (AERC), I submitted an abstract and was invited to make a presentation there.[3]

The evidence that publications about sequestered capital have been largely overlooked by Austrian scholars consists of two types. First, using the Google Scholar search engine, I investigated the frequency of citations to the papers on the subject. Table 1 shows my findings regarding the seven publications on sequestered capital.

I discovered a second type of evidence about Austrian oversight of sequestered capital in 2024, in the process of writing a book review of A Modern Guide to Austrian Economics (Bylund 2022a) for the Review of Austrian Economics (RAE). This book consists of fifteen articles authored independently by a variety of Austrian scholars on a variety of topics. Many of the contributors to this book are prominent in field of Austrian economics. As I read the book, I discovered that none of its chapters cited any publication on sequestered capital: not in its three chapters on entrepreneurship (Sautet 2022; Klein and McCaffrey 2022, and Bylund 2022b); not in its chapter on business cycles (Newman and Sieroń 2022); and not in its chapter on capital theory (Cachanosky and Lewin 2022).

In addition to criticizing the Modern Guide (for overlooking sequestered capital), my book review (McClure 2024) also emphasized the strengths of the book. In particular, Per Bylund’s (2022b) chapter, entitled “Entrepreneurship and the Market Process,” is insightful in its criticism of prominent Austrian capital theorists for being too focused on the role of the interest rate and thinking too little about roundaboutness. Here’s my review of Bylund’s chapter:

Chapter 5 discusses Mises’s view of the promoter-entrepreneur as the “driving force of the market process” (p. 85), distinguishing it from the theories of Kirzner & Hayek and the judgement-based approach (Chapter 4, by Klein and McCaffrey) whose emphases are on non-promoter-entrepreneurs. It highlights publications by Bylund in 2016 and 2020 that analyze actions of the promoter beyond the boundaries of the evenly rotating economy (within whose boundaries Mises could not rigorously analyze the promoter). It urges scholars to think more deeply about the nature and consequences of the actions of the Bylund/Mises promoter-entrepreneur, expressing disappointment that, “Austrian capital theory (e.g., Hayek [1941] 2009; Lachmann [1956] 1978; Cachanosky and Lewin 2022) presents how the capital structure adjusts to changes in interest rate, but the mechanics of such changes, especially the extensions and contractions of the roundaboutness of production are severely undertheorized (Bylund 2015b).” (McClure 2024, 99–100)[4]

Bylund’s (2022b) chapter in the Modern Guide, I discovered, was closely related to discussions in his book The Problem of Production: A New Theory of the Firm. There, Bylund (2016) expanded upon Ludwig von Mises’s discussion of the promoter-entrepreneur. Bylund’s book complements the literature on sequestered capital that emerged concurrently, independently, and unaware of his work. As is clear from figures 1, 2, and 3 and the discussion of them above, the idea of sequestered capital was conceived as an extension of Garrison’s macroeconomics of the capital structure, which was inspired by Hayek’s work on structure of production triangles. Bylund’s (2022b, 86) chapter and his book (Bylund 2016) were inspired by the paradox in Mises’s (Mises [1949] 1998, 256) Human Action in stating that the promoter was a concept that “economics cannot do without” and yet admitting that “the entrepreneur-promoter cannot be defined with praxeological rigor.” Toward addressing this, Bylund (2016) deduced an Austrian theory of the firm as the driver of the market process that evolves and expands, breaking specialization deadlock.[5]

As a result of a conversation about sequestered capital that I had with Mark Thornton at the spring 2025 AERC, he emailed me in September 2025 with a request that I send him papers on sequestered capital that might help him prepare for a Mises Institute podcast he was developing on “private capital.” I sent him my 2025 AERC paper, “Sequestered Capital: An Overlooked Lacuna in the Capital Structure,” and a copy of a forthcoming paper on the 1929 stock market crash (Thomas, McClure, and Horwitz 2025, a preview of which is provided in a later section of this article). A week or so later, Dr. Thornton sent me a link to the September 13, 2025, episode of his Minor Issues podcast, entitled “Black Swans, Sequestered Capital, and the Next Bust.” This episode is a very encouraging development, as it raises awareness about the largely overlooked sequestered capital lacuna in the Austrian theory of capital.

Why Sequestered Capital Went So Long Undiscovered

It seems to me that sequestered capital has gone so long undiscovered for two reasons. The subsections below discuss these.

Discovery Due to Lucky Circumstances and Roger Garrison

Lucky circumstances and knowledge of Roger Garrison’s Hayekian triangle model were key to the discovery, in 2015, of the sequestered capital lacuna by David Thomas and me. David Thomas had been a Silicon Valley start-up entrepreneur who, in his fifties, changed careers by earning a PhD at George Mason University, where his macroeconomics professor, Larry White, covered Garrison’s capital structure model. I had taught myself about Garrison’s Hayekian triangles as a result of having been assigned to teach macroeconomics in the summer of 2013; as a microeconomist who had taught macroeconomics only a few times in my career, I knew that I did not want to focus on aggregate demand and aggregate supply, so in the spring of 2013, I found Garrison’s (2001) book and PowerPoint slides (Garrison 2011) and used them as the basis for the class.

Because both David Thomas and I had had exposure to Garrison’s capital-based macroeconomics, and because he was hired by Ball State University in 2015 and assigned an office next door to mine, we struck up a conversation about the Hayekian triangles in Garrison’s book one day. In particular, our discussion centered around the Hayekian triangle reproduced above in figure 2. David Thomas, with his background as a tech entrepreneur, insisted that R&D belonged as the earliest component in the Hayekian triangle and, furthermore, insisted that it was “somehow” fundamentally different from “mining,” which Garrison placed as the earliest stage, as shown in figure 2 above.

Because I had used Garrison’s (2011) PowerPoint presentation (about sustainable and unsustainable growth), I knew that Garrison had, in that slide show, swapped out “mining” and put “product development” in its place as the earliest component of the capital structure. But simply swapping them was not good enough for David Thomas, who continued to insist that R&D was not only the earliest component, but “somehow” fundamentally different from all of the other “stages of production.”

After many conversations, we went back to Hayek’s (1931) book and realized that his focus there was upon on-the-market circulating capital that Hayek labeled “intermediate products.” What preceded the production of intermediate products were the “original means of production”; R&D were not part of Hayek’s (1931, 228) model of the capital structure.[6] Prices coordinated intermediate products in proper proportion to the output of consumer goods.

After reviewing Hayek’s discussion, we finally saw the unseen! Potential future new products matriculate through these processes unpriced because they are not yet on the market. (Of course! Why hadn’t we seen this before now?) Feedback from Roger Garrison, as a referee for the RAE, in a private email in August of 2016 was in agreement with our insight and analysis. This included a modified Hayekian triangle showing the traditional stages of production as a subset of the full capital structure, whose earliest components are R&D. This modified triangle, as it appears in our 2018 RAE publication (McClure and Thomas 2018a), is reproduced in figure 5.[7] The R&D components are shown in black in figure 5 to illustrate the greater opaqueness of capital usage during these stages relative to the more transparent usage of capital in the stages of production shown in gray.

It turns out that R&D need not be confined specifically to the two earliest stages. For example, Shawn Ritenour (2023, 94–95) correctly observes that “whether technological discovery and innovation occur at the third or thirteenth stage of production, what is certain is that all research and development activity requires saving and investment (in capital). . . .Bringing new production technology into the production structure requires much effort by people operating at relatively higher stages of production.” The placement of R&D as the earliest stage was inspired, as mentioned in this article’s discussion of figure 2, by Roger Garrison, who later replaced the earliest component in the figure (mining) with “product development.” Still, we agree with Ritenour that sequestered capital may be present in other, “higher stages” of production rather than just in the earliest stages. In this regard, it should be emphasized that figures 1 and 3 stand on their own, independent of Garrison’s Hayekian triangle in figures 2 and the modified Hayekian triangle shown in figure 5.

To sum up, the discovery of the sequestered capital lacuna in the Austrian theory of the capital structure was made possible by Roger Garrison’s work on Hayekian triangles and business cycles and the lucky circumstances that put the late David Thomas (1954–2021) in the office next to mine at Ball State University in 2015.

Austrians Focus on the Entrepreneur, Rarely on Creative Destruction

At the 2023 AERC, I presented a working paper, subsequently published with a slightly different title in the RAE (see McClure, Snow, and Thomas 2025), entitled “A Struggle of Incomplete Visions: Hayek’s Examination of Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction Thesis.” As explained there, it was by setting aside creative destruction that Hayek (1945) was able to make the case most straightforwardly that Joseph Schumpeter ([1942] 1950, 167–86) was simply incorrect in thinking that sans creative destruction (which Schumpeter considered the key process distinguishing capitalism from socialism) rational socialist calculation would easily be possible. Having in 1945 debunked this assertion of Schumpeter’s, and having in 1941 decided to abandon the search for a capital theory to undergird his 1931 business cycle theory, Hayek ([1941] 2009) had little apparent reason to think about the creation of an alternative to Schumpeter’s noneconomic, heroic, leading-entrepreneur story about creative destruction.[8]

An Austrian scholar who has thought deeply about creative destruction is Bylund (2016, 2022b). Resurrecting and expanding upon Mises’s discussions of the promoter-entrepreneur and Schumpeter’s discussions of the leading innovator-entrepreneur, he argues that Austrian scholars have paid too little attention to creative destruction. Bylund’s research from 2016 to the present is similar in many ways to the work on sequestered capital that I have engaged in over the same period.

There is one key difference that I want to draw attention to here. By focusing on a single promoter-entrepreneur, overlooking the possibility of multiple promoter-entrepreneurs engaged unknowingly in similar pursuits, Bylund’s explanation ends up echoing Schumpeter’s explanation of creative destruction as a process in which a leading entrepreneur (the innovator with a good brain) inspires, and then a swarm of mere businessmen imitators (with lesser brains) emerge onto the scene.

In contrast, emphasizing that there can be multiple promoter-entrepreneurs working on similar new products unbeknownst to one another, as David Thomas and I do (also, at times, in conjunction with other coauthors) in work on sequestered capital, engenders a richer economic explanation of the swarming. In the sequestered capital literature, superfluous discovery in research and duplicative investments during development stages (prototype discovery, productization, prelaunch inventory creation) are hypothesized as being the drivers of market disruptions.

Bylund thinks of the producers of similar new products as imitators who come into play only after the promoter-entrepreneur has put his or her new product on the market and shown a profit. For Bylund, disruption in the capital structure is caused by the initiating promoter-entrepreneur, who, if successful, inspires imitator entrepreneurs to follow his or her lead after his or her success becomes apparent. The literature on sequestered capital, because it emphasizes more than one promoter-entrepreneur being at work concurrently, provides a clearer picture of what Schumpeter explained as swarming after the leading entrepreneur by small-minded mere businessmen/imitators.

With multiple promoter-entrepreneurs working concurrently in R&D, when the first brings his new product onto the open market, others are incentivized to accelerate getting their similar new products onto the market, ignoring the sunk costs they incurred to that point in their calculations. This provides an explanation for the completions and launches of new-product offerings whose costs (if sunk costs are not understood as irrelevant going forward) appear to exceed those that would be rationally undertaken by firms entering the market only after observing that the launch of a new product was successful. This contributes to ABCT an explanation for error clustering that stands up well against the criticisms that rational expectations proponents have leveled against it.

An Overview of a Just-Published Paper on Investment Trusts

After our empirical inquiry into the Dutch tulipmania was published, David Thomas and I went looking for another historic boom-to-bust event whose timing was explicable in terms of sequestered capital. We decided to investigate the 1929 stock market crash in the US, about which so much has been written. We found, as was true in the case of the tulipmania, that no explanation existed for the timing of the collapse of prices. In our readings about the stock market boom of 1929, we repeatedly came across discussions of the particularly spectacular rise in the prices of investment trusts (alternatively referred to as closed-end funds).

For example, in the introduction to the fifth edition to Murray Rothbard’s ([1963] 2000) America’s Great Depression, Paul Johnson (2000, xiv) wrote, “These crazy trusts, whose assets were almost entirely dubious paper, gave the boom an additional superstructure of pure speculation.” Johnson’s sentiments echoed those of John Kenneth Galbraith ([1954] 1997, 46) who emphasized that “the most notable piece of speculative architecture of the late twenties, and the one by which, more than any other device, the public demand for common stocks was satisfied was the investment trust company.” According to Galbraith (48–50), there were only about 40 investment trusts in the United States in 1921; however, by the start of 1927, there were 160, and that year another 140 were formed; during 1928, 186 were formed; and in 1929, 265 were formed prior to the crash, and “by the autumn of 1929 the total assets of investment trusts were estimated at eight billions of dollars.”

There is, it must be emphasized, a big problem with the credibility of the conclusions reached in Galbraith’s ([1954] 1997) book. On an unnumbered page near the book’s beginning, Galbraith admits that he will not be providing systematic citations to “the general and financial press of the time” where “much of the story of 1929 is to be found.” In essence he seems to be saying, “Trust me on the details on what constitutes ‘much of the story,’ because I’m not going to provide you with the sources that are necessary to check the veracity of my story.” Moreover, Galbraith’s (64) story about the boom in the volume and pricing of investment trusts in the run-up to the bust is so hyperbolic that it needs to be backed up by diligent sourcing: “It is difficult not to marvel at the imagination which was implicit in this gargantuan insanity. If there must be madness, something may be said for having it on a heroic scale.”

Fortunately for Galbraith, no one during the twentieth century ever dug into the details behind his book’s inflated rhetoric. As a result, his story that investor insanity and the sheer madness of unbridled capitalism drove the 1929 stock market crash went basically unchallenged as the book’s sixth edition went to press in 1997.[9] Possibly contributing to the success of that edition, J. Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer (1991) published a seminal paper on investment trusts in the Journal of Economic History (JEH), citing Galbraith’s work as supporting its conclusion that irrational exuberance drove the boom in closed-end fund investing in 1929. De Long and Shleifer also claimed that, by extension and as a consequence, because closed-end funds were such a significant component of the market in 1929 as compared to now, irrational exuberance was the cause for the inflation of the stock market bubble of 1929 generally.

Skeptical of the claims of Galbraith and of De Long and Shleifer, David Thomas and I, along with Steve Horwitz, began searching for the sequestered capital that might have driven the investment trust boom in 1929. In particular, we were hoping to discover some sudden change in the knowledge set of market participants about sequestered capital as a way of explaining the timing of the precipitous decline in investment trust prices in 1929. Our investigations led to discoveries that we optimistically (wrongly, as it turned out) thought would land us a publication in, at a minimum, the JEH. David Thomas was in the process of trying to become tenured, so we started by submitting our working paper to the top-tier journals, which are ranked above the JEH, on the list used by the Miller College of Business at Ball State University.

Here is a summary of our main findings: Investment trusts didn’t appear in any significant way in the United States until the 1920s. Galbraith reports that there were only about 40 of them in 1921, whereas there were about 750 by 1929 prior to the crash. Throughout this period there were two, informationally polar types of investment trusts: blind and transparent. Blind trusts did not publish their portfolio holdings publicly; transparent trusts did. It turns out that in July 1929, the Listing Committee of the New York Stock Exchange decided to impose a new rule that, in order to be listed on the exchange, all investment trusts would have to publish their portfolio holdings. The imposition of this rule, the committee decided, would begin at the end of the third quarter, meaning that published portfolios of blind trusts would start to become public during the third-quarter reporting week of 1929. This was the week when the 1929 stock market crash occurred.

To make the case empirically in a convincing fashion we would have to complete two major tasks: (1) show that the prices of blind trusts corrected during the third-quarter reporting week of 1929 (as a result of the emergence of new information about trusts of this type) whereas the prices of transparent trusts did not correct (because their portfolios had been published throughout 1929—that is, for these trusts, the imposition of the new publishing requirement had no effect); and (2) refute the evidence on which De Long and Shleifer (1991) based their claim that an excessively large premium was paid for investment trusts during 1929 prior to the crash.

Though we completed both of these tasks, our working paper was rejected by one highly rated academic journal after another, including the JEH. (The very first version of this paper was submitted in 2019 to the Economic Journal, where a revise and resubmit was returned to us; unfortunately, our resubmission was rejected.) In 2022, a colleague at Ball State University, Todd Nesbitt, suggested that the Journal of Private Enterprise (JPE) might be an appropriate outlet for our work. Following this advice, after making modifications to tailor our paper to the JPE, I submitted it there. Almost a decade after its first draft was conceived, and nearly a century after the 1929 stock market “crash,” a sequestered capital explanation of the timing of the price correction of investment trusts in 1929 has been published; see Thomas, McClure, and Horwitz (2025).

Toward a Stronger Defense of Capitalism

During the twentieth century, Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises won the calculation debate, explaining the free-market price system as the best means of coordinating dispersed knowledge and individual plans toward mutual agreement and benefit. In the twenty-first century, discovery of a sequestered capital lacuna in the capital structure opens an avenue for Austrian scholars to begin to address what an anonymous referee appropriately emphasized as an “Achilles heel” of ABCT—namely, the absence of insight into the timing of boom-to-bust turning points.

In this regard, the sequestered capital hypothesis has delivered first-ever explanations of the boom-to-bust turning points of two historic cases—the collapse of tulip promissory note prices in 1637 (bringing an end to the tulipmania), and the collapse of American blind investment trust prices during the third-quarter reporting week of 1929 (contemporaneously with the boom-to-bust turning point on American stock exchanges). Providing turning-point insights advantages the sequestered capital explanation over the alternative explanations of animal spirits (Keynes), speculative orgies (Galbraith), and irrational exuberance (George Akerlof, De Long and Shleifer, Robert Shiller, Richard Thaler, etc.), none of which offers operational insight about turning points. These historic-case discoveries suggest the potential fruitfulness of sequestered capital inquiries into other historic boom/bust events that have been held out as prima facie evidence of investors’ irrationality and consequent need for government intervention in, and regulation of, financial markets.

Expanding capital theory to include sequestered capital bolsters the case for free-market capitalism by providing a new challenge regarding the efficacy of another extensive form of government intervention—namely, governmental subsidies of R&D. Either credit expansion or government subsidies of R&D can bloat malinvestment, as illustrated by the enlarged directional arrows for superfluous discovery and duplicative investment in figure 3. Unlike the government agents who award R&D subsidies, entrepreneurs in the venture capital industry engage in an ongoing Misesian process of appraisement; in order for an initial funding tranche to be extended into subsequent tranches, benchmarked requirements must be met.[10] As McClure and Thomas (2021, 92) explained, these benchmarking requirements represent three measurable achievements after the initial funding: “(1) the production of a working prototype, (2) a completed and marketable product, and (3) initial sales to customers.”[11]

I challenge Austrian scholars to think about sequestered capital as they conduct future research on capital theory and business cycles. The dream-case scenario would be the discovery of insights into business cycle turning points beyond historic cases, facilitating prediction in real time. Dream case aside, if future research discovered sequestered capital playing an important role in a series of historic cases beyond the two already discovered (the tulipmania and the 1929 stock market “crash”), it might be the kind of breakthrough that would inspire more non-Austrian scholars to give Austrian-school ideas serious consideration. In the worst-case scenario, might Austrian scholars sequester the concept of sequestered capital out of fear that the rivals of free-market capitalism might pervert it into an addition to the seemingly endless list of “market failures” demanding government interventions? No. I do not think so. Preemptive surrender to interventionists would be impossible for scholars whose intellectual standard bearers are Mises and Hayek.

Matt Ridley, giving a talk about his book How Innovation Works, emphasized that the light bulb was invented nearly simultaneously in six locations around the world. Another example of duplicative discovery is Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russel Wallace’s theories of evolution, which were published in the same issue of the Journal of the Linnean Society in 1858. A further example is Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis and Franco Modigliani’s life-cycle hypothesis. Many academics have discovered that others, unbeknownst to them, were working concurrently on closely related lines of inquiry.

Garrison (2001, 48–49) fully understood, of course, the complexities of capital theory, qualifying the Hayekian triangle he presented (figure 2) as follows: “The graphical presentation of a linear sequence of stages is not intended to suggest that the production process is actually that simple. There are many feedback loops, multiple purpose outputs, and other instances of nonlinearities. Each stage may also involve the use of durable—but depreciating—capital goods, relatively specific and relatively nonspecific capital goods, and capital goods that are related with various degrees of substitutability and complementarity to the capital goods in the other stages of production.” He intended his graphical presentation to put aside “unresolved—and possibly unresolvable—issues of capital theory” in order to “highlight the macroeconomic aspects of intertemporal equilibrium and intertemporal disequilibrium.” As an anonymous referee correctly emphasized: “A model is a simplification and necessarily excludes many real-world elements.”

The 2025 AERC was my second; in 2022, I presented another working paper in which I offered an economic explanation of creative destruction based on sequestered capital, urging that Austrian scholars use it in place of Joseph Schumpeter’s explanation (which Schumpeter admitted was noneconomic). The details of Schumpeter’s explanation are given in the revision of this paper that was subsequently published in the Review of Austrian Economics; see McClure, Snow, and Thomas (2025).

Although not citing Bylund (2022b), Przemysław Rapka (2024) offered this related criticism: “The almost decade-long project of L&C (Lewin and Cachanosky) to make APP (Average Period of Production) the central constitutive concept of ACT (Austrian Capital Theory) and ABCT is again pointless.”

Bylund’s (2016) book reminds me of a paper, uncited in his book, that George Stigler published in 1951 in the Journal of Political Economy. There Stigler (1951) provided an insightful review of various reflections on Adam Smith’s proposition that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market. Regarding expanding firms in the wake of innovation and market expansion, Stigler provided an explanation of vertical disintegration. Because such disintegrations give rise to greater numbers of price signals, a greater Hayekian economy of knowledge is implied; see McClure and Thomas (2019) for a discussion connecting Hayek’s ([1931] 2008, 260–61) discussion of the price fan simile to his 1945 economy of knowledge thesis (Hayek 1945).

Similarly, Ludwig Lachmann ([1956] 1978, 126) qualifies his analysis of the business cycle by explaining that “the Austrian theory, as most other models except Schumpeter’s, ignores the effects of innovation and technical progress (i.e., R&D). It views economic progress primarily as taking place along the lines of ever greater division of labour and specialization of capital equipment, of ever higher degrees of complexity of factor combinations.” Rather than presenting his own theory of innovation, Lachmann (125; italics added) defers to Schumpeter’s: “New products modify the market structure. Here again price inflexibility will for a time tend to hide the facts from the entrepreneurs, but the inconsistencies will show themselves in the end. This situation is best viewed in terms of Schumpeter’s model in which the ‘innovating’ new firms expand into ‘new economic space’ but also restrict the range of action of the older firms.” Emphasis in the preceding quote on “for a time” and “in the end” is added to draw attention to what the concept of sequestered capital adds to Austrian-school thought: insight into boom-to-bust timings.

In retrospect I think that the “original means of production” should be shown as facilitating all components of the capital structure, both stages of production and R&D.

A speculative note: What if Hayek had critically reflected on Schumpeter’s ([1942] 1950, 81–86) story about creative destruction, returned to the capital theory project he abandoned in 1941, and discovered sequestered capital? Perhaps, had he done so, he would have been better able to repulse the criticisms of ABCT by Frank Knight, Piero Sraffa, John Maynard Keynes, John Hicks, etc. With deeper understanding of the nature and causes of business cycles, twentieth-century Austrian scholars might have curtailed the rising popularity of fanciful tales about animal spirits (Keynes), irrational exuberance (Robert Shiller), and speculative orgies (John Kenneth Galbraith).

In the introduction to the first edition of his praxeological inquiry into the causes of the 1929 depression, Murray Rothbard ([1963] 2000, xliiin7) disparages Galbraith’s book as a “slick, superficial narrative of the pre-crash stock market.” For Rothbard (8; emphasis original), explaining the appearance of “a sudden general cluster of business errors” is fundamental question that must be addressed by “any cycle theory.” It is precisely in this regard, as will be discussed in the text, that inquiry into discoordination resulting from capital sequestration during the boom can give ABCT an additional leg up on superficial narratives like Galbraith’s.

As explained by Mises ([1949] 1998, 329), the rational economic calculation of promoter-entrepreneurs is a process of ongoing appraisement which is not based on present prices alone: “Appraisement is the anticipation of an expected fact. It aims at establishing what prices will be paid on the market for a particular commodity.” I am indebted to an anonymous referee for suggesting this qualification, so as not to overstate the sequestered capital discoordination resulting from the absence of market prices on the circulating capital percolating through prelaunch R&D processes.

The venture capital benchmarking process is, as emphasized in footnote 10, indeed Misesian in nature. See McClure and Thomas (2021, 92–93) for a detailed explanation of how entrepreneurs anticipate lower risk and higher expected returns by using successive funding tranches.