Today Vicksburg, Mississippi, is a small and unassuming city where Interstate 20 crosses the Mississippi River. Perched high on cliffs overlooking the river, it was a major economic and military east-west conduit for the Confederacy and by blocking Union advances kept the river to the south open to trade and tactical operations. It also played a powerful role on the north-south vector by preventing the export of midwestern grain and full Union naval control of the river, thereby completing the Union blockade. Both presidents and their military strategists recognized the city as the powerful rook and queen pieces of the Confederacy and that its capture would lead to its collapse. Vicksburg was a daunting citadel overlooking the Mississippi River, the most important internal waterway in North America. It kept the Union army and navy at bay, stymied international commerce from the North, facilitated Confederate trade and troop movements, and connected the eastern and western portions of the Confederacy.

Historians agree that the Union won the Civil War because of superior military might and overall strategic approach. The territory of the Union contained a larger population and greater agricultural, financial, manufacturing, and trade capacity. In particular, the Union controlled the vast majority of iron making, textiles, and shipping capacity. According to the Union’s Anaconda Plan, the strategy of applying overwhelming force based on economic advantage was to be preceded by a shipping blockade of the Confederate coastline and the Mississippi River to strangle the Southern economy before the Confederacy’s full-scale invasion.

Prior to hostilities, it was far from clear how the war would turn out. The view that the Union could not defeat the Confederacy was based on the South’s large size and military advantages such as internal lines and the ability to fight a defensive war on its own soil. Considering these tactical advantages, it was not exactly a David-versus-Goliath scenario.

In historical terms, Gettysburg was the turning point in the Civil War.[1] Occurring alongside the fall of Vicksburg—the midpoint of the war—and the Gettysburg Address, the battle’s military importance is often overstated. Debates about its significance and strategies have tended to misdirect attention away from the fundamental causes of Union victory toward the vagaries of the battlefield, tactical choices, and random luck.

Military historians have shown that various military outcomes could have turned out differently with different tactics and military leaders. While such ex post facto gamesmanship is interesting and important, it is no substitute for sound strategic planning and institutions in determining ultimate outcomes. For our analytical purposes we are concerned with the practicality of ideological views, the importance of political institutions, and the impact of economic policies on the outcomes of military conflict. Hence, this is a forward-looking investigation rather than mere Monday-morning generaling.

Given all the drama, suffering, and tragedy woven into these events, as well as the emotions and feelings they evoke, it is important to stay grounded in the direct purpose of this article. As an exercise in applied economics, we deduce the economic effects of the policy of impressment—that is, the forceable taking of economic goods at below-market prices. We then appraise its relative significance and interpolate those findings into the well-known course of events of Ulysses S. Grant’s famous Vicksburg campaign.

A complete critique of Civil War military strategy and postwar interpretation of outcomes would take us too far afield, but it is no exaggeration to summarize Union strategy and even postwar US strategy as the employment of superior military strength. Although Grant’s victory at Vicksburg has been overshadowed by Gettysburg, the American Battlefield Trust recently highlighted its immense importance and enduring lessons as follows: “Only (in) the coming decades would Grant’s accomplishment (at Vicksburg) be recognized. Late into the 20th century Coalition forces in the 1st Gulf War were still using tactics inspired by Grant’s Vicksburg campaign” (American Battlefield Trust 2019, at approximately 19:00).[2]

According to this strategic view, defeat is a failure to commit to the often risky[3] use of sufficient military strength. Inferior forces have no chance of victory beyond foreign intervention or dumb luck. This historical perspective would seem to leave any potential adversary of the US, or any modern superpower such as China, with no options: resistance is futile indeed![4] We crack open that debate here by exposing a fundamental flaw in Confederate ideology, strategy, and policy, and we explain that flaw’s decisive role at Vicksburg.

Superior forces are not always victorious, and underdogs win their share of battles and wars (see, for example, Arreguín-Toft 2005). The accumulation of military and social losses, or even victories, undermines superpowers and leads to their downfall.[5] The key to victory for underdogs is the adoption and consistent application of a winning strategy that defeats superpowers. We suggest that such a winning strategy follows from the ideology of liberalism and free market economics. David defeated Goliath by applying a comparative advantage gained from a seemingly tangential aspect of his practical market experience. The military failure of the Confederate government is illustrated here by the role that impressment policy played in the downfall of Vicksburg.

The approach taken here runs counter to the general view that portrays the prewar agriculture-based South as relatively opposed to government involvement in its economy. In our view, the Confederate war effort embraced a “big government” strategy that was insufficiently committed to liberal principles, such as states’ rights and limited government. Economic historians such as Hummel (1996) and Majewski (2009) already recognize that the Confederacy broke with the liberal tradition and moved toward more extensive government involvement in the economy, although both authors show that such tendencies were latent prior to the war. Hill (1936) even makes a compelling case that the application of state socialism in the Confederacy was very effective but was attempted on too small a scale and too late in the war to have changed the outcome.

This article opens with two quick sections on the economic theory of war and the theory of war strategy. These theories bolster the claim that the Union and Confederacy identified Vicksburg as the key position of the war and devoted large amounts of resources to its control. We illustrate the failure of the Confederacy in its policy of impressment, comparing the actual and expected impacts of this policy in terms of Grant’s final Vicksburg campaign. These results suggest that impressment was responsible for Grant’s surprising success in two central respects: (1) the logistical advantage it created for his campaign crisscrossing the state of Mississippi and (2) the absolute advantage it created for the success of the siege of Vicksburg. We thereby provide a better understanding of the fall of Vicksburg and the outcome of the war while illustrating the importance of political ideology in terms of economic effects and military outcomes.

Mises on War Economics

“It would be foolish to deny that the profit system produces the best weapons. . . . The worst enemies of a nation are those malicious demagogues who would give their envy precedence over the vital interests of their nation’s cause” (Mises [1949] 1998, 823). [6]

Ludwig von Mises fought in World War I, escaped a Nazi manhunt during World War II, and fought a lifelong intellectual battle against all forms of socialism, including fascism and communism. He wrote extensively about the pitfalls faced by historians but even more voluminously about money, government interventionist policies, and comparative economic systems.[7] Mises integrated the economics of war into his comprehensive analytical system, rather than ignoring it or treating it as a special case.[8] Most importantly, he stressed that all historical interpretation is necessarily rooted in some kind of economics and that correct economic theory must be employed for the proper interpretation of historical events.[9]

In fact, he used the example of the American Civil War to make telling observations about the outcome of World War II. He connected the economic disadvantage and policy failures of Germany in World War I and World War II to those of the Confederacy. Recognizing the importance of the Industrial Revolution, Mises drew on the example of the “free trade” South to highlight the dramatic failure of anticapitalist policies that led to the defeat of both nations.[10]

For Mises, the successful conduct of war in the modern age is a matter of relying on the profit motive to direct civilian commercial production toward military arms, accoutrements, and materials, paid for by extracting taxes and issuing bonds. Success and failure are thereby determined by the extent—relative to its opponent—to which a nation relies on the profit motive of entrepreneurs over bureaucratic management. His conclusion will play a key role in this reinterpretation of the Vicksburg campaign.

Mises devotes his analytical section on the economics of war to the key problem of a nation’s comparative disadvantage. Mises ([1949] 1998, 825) chastises European military experts for their failure to learn the lessons of the American Civil War, where, for the first time because of the Industrial Revolution, “problems of the interregional division of labor played the decisive role.” He notes that Germany did not break the British blockade in World War I and World War II and instead adopted ersatz production as a foundation of its policy of war socialism. He considers this the fatal flaw in its grand military strategy.

Germany’s ersatz program attempted to produce domestically the fuels, materials, and foodstuffs it had previously imported. Likewise, the Confederacy’s failure hinged on its costly attempt to produce its own armaments and ammunition as well as a broad number of other manufactured goods and foodstuffs. Mises describes ersatz as production that is intrinsically inferior in quality, produced at a higher cost, or both.[11] He concludes that this policy was critical to the outcome of the American Civil War and Germany’s defeat in both world wars.

Throughout his voluminous written work, Mises emphasizes the importance of economic calculation by entrepreneurs as the key to success for the overall economy (see, for example, Mises [1922] 1951). He also demonstrates that bureaucratic direction of resources cannot be motivated by profit and is necessarily inefficient. The ersatz strategy eschews comparative advantage and attempts to fill the gap with production that is economically inferior even when undertaken by entrepreneurs motivated by profit because it produces a distinct economic loss and, therefore, a military disadvantage. Napoleon, the kaiser, Hitler, and the Confederacy did not take sustained active stances against the blockades but instead focused on ersatz strategies. The production and international trade disruptions caused by the ersatz approach were primary causes of defeat in each case.[12]

To summarize Mises’s conclusions, although war is incompatible with capitalism, the reliance on entrepreneurs, the profit motive, the price system, and trade is key to military success (see Newman 2023). Capitalistic nations will typically defeat socialist nations in war. Government interference is counterproductive, and government production is highly ineffective and uneconomical. While international trade is a more complicated phenomenon, the results of the policy of impressment investigated here are straightforward in comparison and easy to understand at the microeconomic level because of its similarity to theft.

The Economics of Military Strategy

An understanding of the underdog strategy begins to emerge in Eastern military theory in Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Liddell Hart (1967, 335) later formulated a generalized version of strategy that places less emphasis on generals and battle formations and instead conceives of war as the attempt to achieve “the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy.” According to Liddell Hart (25; emphasis added), “effective results in war have rarely been attained unless the approach has had such indirectness as to ensure the opponent’s unreadiness to meet it. The indirectness has usually been physical, and always psychological. In strategy, the longest way round is often the shortest way home.”[13] Liddell Hart criticizes the frontal assault in favor of the indirect means that epitomized Grant’s Vicksburg campaign.

Liddell Hart (1967, 336; emphasis in original) also advocates for asymmetric warfare in the economic context of ends and means. “Strategy depends for success, first and most, on a sound calculation and co-ordination of the end and the means. The end must be proportioned to the total means, and the means used in gaining each intermediate end which contributes to the ultimate must be proportioned to the value and needs of that intermediate end—whether it be to gain an objective or to fulfil a contributory purpose. An excess may be as harmful as a deficiency.”[14] Liddell Hart is emphasizing efficiency within a process aimed at achieving a goal. In economics, this ends-means framework was first proposed by Ludwig von Mises and Lionel Robbins only a few years prior to Liddell Hart’s early work on military strategy. Now widely accepted as the defining principle of the economics discipline, it is also a cornerstone of military strategy.[15]

While economic principles apply to all military combatants, my hypothesis here is that a winning underdog strategy must be more stringently grounded in economizing compared to the constraints on a superior force. Here, the underdog military strategy must be obedient to the overall, or grand, strategy based on a free market ideology and policies dedicated to ensuring that (1) a free market economy produces the maximum possible amount of goods, (2) this economic maximum produces the largest possible tax base to sustain the smallest possible military sector, and (3) this military minimum is augmented by the flexibility of the private sector to provide “invisible hand” assistance to the military, such as militias and partisan warfare. As a result, the “pure military strategy” for underdogs must emphasize characteristics such as local independence, militias, surprise attacks, guerilla tactics, spy networks, communication, and exchange as primary aspects of “organization” and avoid a central command of resources.[16]

The components of this overall strategic vision are not an à la carte menu for political or military command to choose from but are all mutually reinforcing in the general strategy for achieving the ultimate goal.[17] This is a matter of practicality, not pedantry, as the interaction of the policies of impressment and inflationary finance will demonstrate.

The organization of the Confederate government contributed to its subsequent military strategy and the adoption of economic policies that led to predictable consequences and ultimately to defeat. At the heart of this failure was an insufficient ideological commitment from Confederate leaders, politicians, and citizens to the political philosophy of liberalism and the free market economy. This in turn resulted in an overreliance on the policies of war socialism in the Confederacy’s grand strategy. Confederate political and military leadership adopted the West Point philosophy of war and military strategy, but this ideology also predisposed the government to nonmarket procurement processes, such as the policy of impressment (see, for example, Bensel 1987).

Impressment policy allows government officials to take goods and services from producers at government-determined prices. War conditions naturally suppress production, decrease supply, and increase prices throughout the economy. Inflationary and speculative conditions further inhibit the government’s ability to access goods and services. Impressment policy allows the government direct access to existing resources for military operations. But suppliers prefer this only to outright confiscation by enemy forces, making it an exception to the rule of the following analysis.

Vicksburg gave the Confederacy a comparative advantage in defense: a large economic advantage at a low military cost. Strategically, it could have been better defended at an even lower cost if the underdog strategy had been fully utilized. Still, Confederate impressment policy was probably a necessary condition for Grant’s rapid though indirect success in taking Vicksburg.

Impressment Policy and the Defeat of Vicksburg

After attempting every other approach, the Union defeated the Confederate position at Vicksburg with a risky flanking maneuver, beginning with an end run and an invasion of southern Mississippi behind enemy lines. It then moved a large army east to the capital, Jackson, before turning west to lay siege and force a surrender. Grant’s maneuver put a large Union force in danger of total destruction, and impressment policy was the key unrecognized factor in Grant’s ease of maneuver and the speedy Confederate surrender of Vicksburg.[18]

The unintended economic consequence of impressment in Mississippi was twofold. First, it guaranteed that food, forage, and material supplies would be more readily available in the Mississippi countryside, where Grant operated with limited, extended, and easily threatened lines of supply. Second, it guaranteed that markets would be greatly hindered and resources such as food less readily available in Vicksburg. As a result of these two factors, impressment policy increased the probability of success for Grant’s operations in Mississippi and decreased the probability of a successful Confederate defense of Vicksburg.

Impressment allowed Confederate officials to take supplies from producers and supply-chain “speculators” at government-determined prices, meaning that owners would receive below-market compensation.[19] Historians consider impressment a necessity that came at a terrible cost, recognizing that the policy violated individual and states’ rights, caused hoarding and speculation, and was a major contributing factor in the decline of civilian morale.

It certainly had an impact on hoarding[20] and speculation.[21] Farmers were more likely to “hoard” their production on their farms and plantations rather than bring it to market to face possible impressment. If impressment induced producers to hoard production, it would have made the Mississippi countryside relatively abundant with supplies, making supplies relatively scarce in Vicksburg ahead of the siege.

Taking product to market meant risking impressment, which was really a partial confiscation. The below-market prices meant that the distribution of resources was necessarily chaotic, with areas of acute scarcity where Confederate officials typically operated, especially in cities and near war zones.

Todd (1954, 167) notes that “reports were heard of large quantities of supplies collected by impressment in various depots, but more frequent were the reports advising of the great difficulty experienced by the military authorities in their attempts to secure subsistence for the armies.” All the reports referenced by Todd are from the Mississippi area during 1863 and 1864.

The fact that impressment was not voluntary encouraged producers to avoid Confederate officials, who were more prevalent in and around market cities such as Vicksburg. This discouraged supply from reaching cities for both the military and the civilian population, producing acute scarcities, higher market prices, and general hardship. Todd (1954, 169) reports on the burdens of the impressment policy near cities: agents would “pounce upon supplies on the way to city markets, thus giving rise to grave suffering among the urban population, raising prices still higher, and inciting the bitterest feeling against the military authorities by country and townspeople alike.”

The primary problem of this distributional chaos was quickly surpassed by the even bigger problem of production levels. Prior to impressment, producers would have been producing at levels consistent with free market prices, making supply adjustments to the new prices brought about by military demands and the increased scarcity of production inputs, such as managerial labor, working capital, agricultural implements, and work animals—all made scarcer by the war itself and declining over time. Early in the war, ad hoc government impressments took place and were later turned into legislation by the Confederate Congress. Both the ad hoc and legislated policies would have severely disrupted supply conditions and hindered market adjustment by entrepreneurs.

Once government impressment had taken place, producers would have reduced their planned levels of production in line with their speculations about the prices they would receive. Disastrously, producers would tend to severely reduce or eliminate the production of goods highly desired by the military. Likewise, they would increase the production of goods not desired by the military and those that were easy to conceal from procurement officers.

Todd (1954, 167–68) cites Governor Brown of Georgia on how impressment would cause producers to “withhold the supplies from the market and cause them to be secreted and concealed from the Government agents.” Brown recommended that the problems of distribution and failing production could be reversed by paying market prices, because impressment encouraged concealment, evasion, and idleness rather than the production of vital goods. Hummel (1996, 230) also emphasizes the destructive impact of impressment on the economy and citizen morale.

Thus, the overall impact of impressment policies would have reduced production of the materials needed for the war effort. Taxing in kind and impressing slave labor—also considered low-cost means by both officials and historians—would have also directly reduced production, especially food and valuable exports such as cotton and sugar. These export products were necessary to finance the importation of highly valued manufactured and military goods.

The below-market nonvoluntary prices would also have induced Confederate officials to make larger “purchases” because neither the agents nor the government was actually giving up much value in return. They were not required to make hard tradeoffs in the normal sense. This would have led to a waste of productive resources, and there is evidence that large amounts of Confederate supplies went unused, decayed in storage, or were destroyed or captured by the enemy.[22] All four forms of this resource destruction are symptomatic of improper valuation of purchases rooted in the incentive structure created by impressment policy. Todd (1954, 169) describes the large-scale rotting of “corn, bacon, potatoes, wheat, salt, and hides” in Confederate storage.[23]

In military strategy, procurement plays the central role. Here, the obvious problem is insufficient resources for the military, but the less obvious but still fatal flaw of military procurement is the acquisition of too many resources for the military or too few for the productive civilian population. While the purpose of impressment was to acquire more resources for the military, economic analysis indicates its impact on supply and stewardship may have reduced the total resources the Confederacy could use on the battlefield while intensifying civilian impoverishment and demoralization.

Market prices, taxation, and being forced to pay with specie would have forced the Confederacy to economize on the size of the military. Confederate quartermaster officials would have been better stewards if they were compelled to buy supplies priced relatively low at the time of purchase—for example, choosing between corn and wheat or between pork and beef depending on market prices. This economizing would effectively place a higher floor under market prices, which would support suppliers.

Inflation is a common economic problem during modern war, but it is also an attractive—almost irresistible—policy for politicians to adopt.[24] The problem is not the higher numbers following the dollar sign but that too many resources are transferred from the private to the public sector at too low a cost, producing waste and allocation problems. We simply note that the Confederacy resorted to printing money for a much higher percentage of its public finances than the Union. The bulk of the paper money issued was for the impressment of goods, forcing the weight of inflation directly on the backs of the productive population. This was a huge problem in itself, but here we are also using inflation as an example of how government intervention policies have compounding negative effects and why underdogs should avoid all policies that undermine the functioning of free markets.

Beyond expanding the nominal military budget, we will now explain and demonstrate how the policy of money-printing inflation diminishes overall production and civilian morale through the interaction of higher prices and impressment. The difference between market prices and government-determined impressment prices is the “impressment tax,” which occurs at the point of sale. But the erosion of purchasing power from higher prices continues for the seller until money is actually received from the government and spent in the market. This gap in time widens the difference between government and market prices and greatly increases uncertainty for suppliers. Under normal conditions, the supplier would purchase particular goods at particular times according to an economical schedule. Under high inflation, the negative impact of impressment prices would be like being forced to spend your entire monthly paycheck the day you received it on whatever was available, or else watch its value shrink day by day.

Another way to imagine and gauge the interaction between inflation and impressment and its impact on production is to imagine a seller who has the right to sell his production at market prices for specie money. In a wartime economy, this hypothetically privileged producer would have a strong incentive to produce, market, and sell. He would have far less of an incentive to hoard or speculate on higher prices. This would be especially true when credit is restricted by war and working capital must come from sales revenue. Likewise, similarly privileged wholesalers and speculators would have an enhanced incentive to purchase, store, and sell their inventories. Todd (1954, 165) speculates that monetary inflation and anticipated rising prices was the number one reason producers would hold out their supply on the potential for higher prices in the future.

In fact, the hypothetical privileged producer and privileged wholesaler would have a special incentive to warehouse their impressment-free inventories in militarily protected cities, such as Vicksburg and Atlanta, that were defended from enemy confiscation and destruction. Under the right economic conditions, Vicksburg might have been overflowing with supplies when Grant’s army arrived on its eastern outskirts. With the cupboards and warehouses of Vicksburg fully stocked, its citizens and soldiers certainly could have held out for more than forty-seven days.

Impressment Feeds Grant’s March, Starves Vicksburg

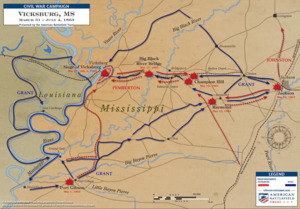

With his supply base reaching back to Memphis, Grant’s gambit began several miles upriver from Vicksburg where his army traveled west of the Mississippi River through the swamps and backchannels of Louisiana. It merged again with the Mississippi twenty-five airline miles south of Vicksburg in enemy territory. From there, the army of forty-five thousand moved northeast to the state capital of Jackson, pushing out Johnston’s army. It then moved west along the railroad to Vicksburg, where it lay siege to the city.[25]

Prior to this campaign, Grant had made several attempts on Vicksburg without success. The final attempt was seen as the riskiest of all possible ventures: moving a large army a long distance through enemy territory with an overextended and vulnerable supply line. If the supply lines had been cut or disrupted and his army confronted by a significant force, it could have spelled disaster. This would have been a devastating psychological and political blow to the Union war effort and might have proven to be the battle that ended the war.

The long period of inaction and frustrated attempts made leadership in Washington, DC, the general public, and Grant himself impatient for achievement at Vicksburg. Grant had at his disposal a great numerical advantage in men and guns, complete naval superiority, and a virtually unlimited source of replacements and supplies. He understood that the logistics of his new scheme was, according to Ballard (2005, 106), “mind-blowing.” The Union general was still very tentative and uncommitted, but he was pressured into action by onerous words from his superior, General Haddock: “The great object of our line now is the opening of the Mississippi River, and everything else must tend to that purpose. The eyes and ears of the whole country are now directed to your army. In my opinion, the opening of the Mississippi River will be to us of more advantage than the capture of forty Richmonds” (quoted in Ballard 2005, 109).

Grant continued to worry that his trusted friend and confidant General William Tecumseh Sherman did not trust the plan. According to Ballard (2005, 133), Sherman “admitted that he had never thought the idea of crossing below Vicksburg would work.” But Grant gained confidence when his supporting naval flotilla passed Vicksburg, which had not made the necessary corrections to its artillery fire after previous failures and whose commander, General Pemberton, had decided to ignore local advice and not contest the landing south of the city. It was Grant, rather than Pemberton, who acted in accordance with Liddell Hart’s playbook.[26]

Unmolested, Grant and Sherman established an effective base on the Mississippi River, but the inland terrain was perfect for a well-distributed defense to delay and harass military and supply movements. It was here that Grant declared the army would carry what it could and not maintain a line of supply. Grant instructed Sherman that they would depend on rigorous foraging from the land. As the campaign moved inland, it contained three large army groups with large wagon trains of ammunition and high-value food items. It received only one resupply from the river during the campaign.

Under previous orders, Grant only become aware of the possibility of disregarding the axiom of maintaining a line of supply in late 1862. Prior to Vicksburg, it had never occurred to him to do so inside enemy territory (Grant [1885] 1962, 150). Yet in May 1863, sensing authorities would disapprove, he abandoned his supply base on the Mississippi as the only course “that gave any chance at success” (184). Confederates were aware of Grant’s potential weakness of being confronted in force while he operated with limited supplies. Johnston wrote to Pemberton, “Can Grant supply himself from the Mississippi?” (194).

Grant ([1885] 1962, 195) also recalled that Pemberton attempted to get between Grant and his base: “I however, had no base.” Indeed, Grant’s army could easily live off the land since “beef, mutton, poultry and forage were found in abundance. Quite a quantity of bacon and molasses was also secured from the country” (185). Every plantation also had a grinding stone, so that Union soldiers often even had fresh bread (185). There is, therefore, ample evidence that foraging yielded good results for Grant.

Ballard (2005, 123–4) concludes that the Confederates further aided Grant with their inexperience and ineptness because “if Pemberton and his officers had had any kind of foresight, they would have ordered supplies taken away or destroyed along Grant’s line of advance.” The lack of food along the way would have kept the Union army dependent on wagon trains slowed by bad roads and bad weather and potentially threatened by enemy raids. Instead, “Union forces in the advance had top choice of local supplies . . . and . . . the march encountered little resistance and ample opportunities to raid private structures and property.”

There is much more to this story, but for our purposes, the most glaring of Grant’s great weaknesses was his lack of a supply base, and that weakness was left unchallenged. More to the point, Grant had little difficulty acquiring adequate supplies along his line of march for an army larger than the combined Confederate forces. While many policies and decisions contributed to this relative ease, we attribute the bulk of the surplus inventory in the countryside to Confederate impressment policy, despite the otherwise impoverished wartime economy.

Now imagine the counterfactual hypothetical scenario of no impressment and no policy-induced hoarding leading to surpluses in the countryside. The dangers of war and the impoverishing war conditions would have made people keen to produce and sell their production for money—an easily hidden, transported, and reliable source of value.[27] Producers would have been eager to produce goods, particularly those demanded by the military—such as food, saddles, and wagons—which would have been in demand and priced relatively high. Under these conditions, an emphasis would have been placed on transferring production from the suppliers to the military, particularly to military depots in fortified cities. One can easily imagine farms and plantations eagerly transporting food and other production in newly made wagons drawn by oxen, mules, and horses to be sold at military or railroad depots.

The consequence of this alternate history is that Grant’s army would have had greater difficulty supplying its needs by foraging. The lack of foraging opportunities would have diminished the army’s effectiveness and speed, increased its reliance on a long and serpentine supply chain over enemy territory, and made the Union commanders more cautious. It would have made the army more susceptible to supply suppression tactics, such as destroying supplies in barns and warehouses, as well as ferries and bridges.[28]

The Union army also would have been more susceptible to threats and disruptions to its supply chain going back to its supply base, dissipating its offensive force as it moved forward. The ability to freely forage and capture supplies allowed Grant to pursue the indirect strategy of first attacking and neutralizing the forces in Jackson before proceeding to Vicksburg. Without foraging, Grant might have failed altogether or, more likely, been confined to a direct attack path north to Vicksburg along the Mississippi with the support of the navy—a path that Pemberton was better prepared to defend with existing resources and reinforcements from the east.

We are not going to belabor the point about how impressment policy adversely affected the ability of the Confederates to defend Vicksburg (they succumbed to Grant’s siege after only forty-seven days). Surprisingly little has been written on the factual data concerning the siege from either side, although there are some informative firsthand accounts. What is known by all accounts is sufficient for our purposes. The obvious facts support the notion, already described in theoretical detail, that impressment policy suppressed the supply of vital materials demanded by the military, particularly where the quartermaster’s office operated in important military cities.[29]

The defenders of the Vicksburg had plenty of artillery to prevent gunships and supply ships from passing by on the river and to keep Grant’s army and artillery at a safe distance. They had plenty of men and quality guns inside the city to prevent the Union from storming and taking the city. The main deficiency was a lack of military preparation, especially in terms of food and ammunition. With limited rations, which were soon cut, the soldiers were practically starving and had little energy to participate in a sustained fight from the inadequate and hastily improvised trenches.

Ammunition was also lacking so that the large cannons of Vicksburg could not be fired sufficiently to keep Grant’s own field and siege cannons at a safe distance. The inability of Vicksburg’s artillery to suppress Grant’s and the Union navy’s artillery meant the city faced a constant barrage of death, destruction, injury, and sleep deprivation. Despite the two-year lead time, the city’s defenses were remarkably unprepared and unorganized for Grant’s siege. The last-minute, makeshift efforts by the military and civilian population are often lauded for their ingenuity and effectiveness, but they were as wholly inadequate as the supply of food.

Conclusion

Grant should be considered a military genius for his innovative Mississippi campaign that captured Vicksburg, the single most important defensible piece of the Confederate war effort. In contrast, to say that the Confederate leadership was inept would be generous—it did not offer a serious, well-organized challenge or even a “strategic retreat” to Grant before it became trapped inside the city. We can trace these failures back to military strategy, military organization, and political ideology, but our primary purpose here is isolated to the economic analysis of impressment policy and its likely effects. The incentive pattern predicted by theory emerges clearly during the campaign. Grant disembarked on a desperate and risky venture into rural Mississippi, only to find that his army had entered, unchallenged, a land of milk and honey. Grant then cornered the bulk of Confederate forces in a city that was unprepared and without sufficient food and ammunition to survive a siege. What had started out as a desperate and risky move on Grant’s part turned into a stunning and complete victory. We can now say that the Confederate’s own procurement policy was the prime determinant of that outcome.

It is not surprising that historians and dramatists place the little Pennsylvania town on the center stage of history. Geographically, it was roughly situated between the two nations’ capitals. The battle partitions the war at a midpoint in time between the first half of the war, when the Confederacy was still competitive, and the second half, when it was in retreat. In contrast to the civilian carnage and pitiful military surrender of Vicksburg, Gettysburg was an open clash of equals, with all the pomp and circumstance of medieval warfare fought betwixt the two contending kingdoms.

Whether this is an incorrect conclusion based on military science or a propaganda statement is immaterial for our purpose, which is to show the current perception of the historical events. As they explain on their YouTube channel, “The American Battlefield Trust is America’s largest non-profit organization (501-C3) devoted to the preservation of our nation’s endangered Civil War, Revolutionary War, and War of 1812 battlefields. The Trust also promotes educational programs and heritage tourism initiatives to inform the public of the wars’ history and the fundamental conflicts that sparked it. Our office is located in Washington, D.C.”

Lincoln’s generals were often reluctant to apply superior forces in a way that they considered reckless and unnecessary, preferring to allow General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan to have its full effect. Lincoln, however, faced political constraints and wanted his generals to take a more offensive posture, which he eventually found in the work of General Grant and General Sherman.

Friendly compromise is an alternative to war, but a lack of military alternatives in any compromise would only embolden abusive behavior on the part of a superpower and lead to heavily one-sided agreements to the inferior party’s disadvantage.

This was Osama bin Laden’s explicit strategy against the United States during the war on terror. See Alva (2021).

I interpret envy as the envy of political operatives, who seek control of resources over the claims of the original owners, who earn profits by hiring labor and producing output at the lowest possible cost.

The reader is encouraged to read Mises (1949, chap. 34, esp. sec. 2) on this point. For a recent survey of Mises’s contributions, see Burr (2024).

With respect to tariff protectionism, for example, Mises noted that a government’s domestic intervention in the economy will lead its external intervention (protectionism, tariffs, and foreign policy) and that such foreign intervention is a leading cause of international conflict and war. See Thornton (2025).

Mises ([1957] 2007) took an integrated approach to the study of the social sciences. His views on history, most notably in his book Theory and History, were unique at the time and widely misunderstood. To briefly summarize, Mises believed that history must necessarily follow the constraint of his theory of human action—namely, that man acts to achieve ends and that the results of markets are based on this dictum and respond predictably to change and government intervention. In contradiction to the then-popular view that theory follows history, Mises made waves in his claim that history must necessarily follow theory. Here, the historian has the difficult task of weaving a narrative of the facts consistent with theory.

Writing in the aftermath of World War II, his readers could be more objective toward the example of the Confederacy and its more obvious and better-known departures from free market policy—notably, its King Cotton strategy.

Ersatz products can mean anything from fake replicas to synthetic substitutes. In Mises’s economic conception, it necessarily means goods that are of inferior quality or have higher opportunity costs of production per unit. The fact that ersatz production could make technically superior products does not negate the policy’s overall economic weakening effect, because too much effort and resources are necessarily squandered to achieve such results.

What Mises failed to consider was that the Union blockade was only effective in suppressing the Southern economy and the Confederate war effort because of Confederate government policies, which had the unintended consequence of bolstering the Union navy’s efforts in what was predicted to be another “leaky affair.” These policies and their connection to the effectiveness of the blockade and the outcome of the war are detailed in Ekelund and Thornton (1992, 2001); Ekelund, Jackson, and Thornton (2004, 2010); and Thornton and Ekelund (2005).

In economics, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk introduced the concept of the “roundaboutness of production” where production that is more time consuming and more capital intensive can be more productive in terms of producing the most value in production at the least cost.

The general reader may have a difficult time interpreting this quote, but it should make perfect sense to the average entrepreneur, mob boss, or terrorist group leader.

Mises ([1920] 2012, [1922] 1951) began developing the ends-means framework in his work on the economics of socialism. Robbins (1932) is credited with the introduction of this definition to the economics profession although it is derived from Mises’s work.

Pure military strategy is described by Liddell Hart (1967, 336) as follows: “Strategy depends for success, first and most, on a sound calculation of the end and the means.” In terms of “grand strategy,” the organization of the military should depend primarily on local government, state government, and independent units to enforce the proper orientation. The central government would be tasked only with the defense of national capital, its alternative or regional supply bases, naval operations, and foreign affairs.

Comprehensive support for this claim will be based on future research. For example, military historians often claim that monetary inflation was a necessary measure for the Confederacy, but the alternative approach argues that inflation permitted the overacquisition of resources by the central government, which resulted in a large amount of waste on the battlefield and otherwise. Without money printing, central planners would not have been able to raise and equip large armies with which to confront the enemy in pitched open battles, with the attendant heavy losses of men and material.

Grant’s risky tactic not only succeeded in winning Vicksburg but also ignited his rise to the overall command of the Union forces. Grant’s success depended heavily on taking advantage of the Confederate government’s flawed economic policy—particularly its policy of impressment. If Grant’s plan had backfired, the Union would have soon lost the war at the ballot box.

See Todd (1954, 165–71) for an authoritative source. Military officials used an ad hoc system of impressment, but as problems and abuses developed, the Confederate Congress passed a law on March 26, 1863, to officially authorize and regulate the practice of impressing private property for public use.

“Hoarding” is now a derogatory term to denote what is considered an irrational activity that can harm society by increasing the scarcity of money and goods. In recent years, it has even been considered a psychological disorder. But these designations are a function of the ideological dominance of Keynesian economics and statism. Psychological problems with hoarding are no greater than those surrounding other activities, or they may be a manifestation of the ingrained consumerism resulting from Keynesian policies. Hoarding is and should be considered rational behavior in response to external stimuli and even laudatory economic behavior associated with saving and preparing for emergencies and rainy days—the Boy Scout syndrome.

Speculation is also generally used in a derogatory sense: the speculator acts from self-interest to the detriment of society. The implication is that speculation causes consumers to pay more for and have less access to goods, but nothing could be further from the truth. Speculation is the purchase of goods where they are cheap for the purpose of reselling them at a higher price at the speculator’s risk. It can involve changing the location or timing of sale and consumption, moving a good from where it was less desirable to where it is more desirable, with the speculator bearing the risk of time and place. This raises the price received by producers in places and times of low demand, and it reduces prices and increases availability for consumers in places and times of high demand. Speculation is pervasive in a market economy.

All four of these forms of resource destruction are symptomatic of improper valuation of inventories that begins with the incentive structure created by impressment policy.

Below-market wages would have led officials to acquire too much slave labor and to place them in abusive conditions.

See Salerno (1990).

For context, the white population of the entire state of Mississippi in 1860 was 350,000, with many men dead or fighting in other states.

Grant had sent a calvary raid from Tennessee to Baton Rouge, well behind enemy lines, as a distraction to disrupt and psychologically undermine the Confederate defense.

Earl Miers Schenck reports on the “embarrassment” of cotton enthusiastically being sold through enemy lines for gold and “enormous profits” (Grant [1885] 1962, 124–25). Readers should consult this work for Grant’s own views on logistical matters during this campaign.

As noted earlier, utility analysis shows that producers would have preferred Confederate impressment in these circumstances to a total loss to enemy combatants.

See My Cave Life in Vicksburg (1864), Balfour (1983), Foote (1995), Groom (2009), Hoehling (1969), Mitcham (2018), and Urquhart (1980) for information about the city of Vicksburg during the siege.