For the rest of his life Grant was convinced that vetoing the Inflation Bill was one of the greatest things he ever did for his country.

—Geoffrey Perret, Ulysses S. Grant: Soldier and President

Thus, 1873 is worth reexamination.

—Charles P. Kindleberger, “The Panic of 1873”

Historically, there has been a great deal of negativity surrounding Ulysses S. Grant as both a Civil War general and a postwar president. Biased stories propounded by personal enemies drove the negativity, which helped form the basis of popular negative narratives that to some extent continue to this day. Such narratives are being reevaluated and debunked (e.g., Calhoun 2017; Chernow 2017, R. White 2016, and Perret 1997),[1] but thus far President Grant’s actions during the Panic of 1873, which occurred a short time into his second term, have not yet been economically reevaluated. This article examines Grant’s actions during that panic and its aftermath, which was known as the “Great Depression” until the depression of the 1930s assumed that title.

Although he had no background in economics or finance, Grant’s national financial (including monetary) understanding and expertise progressed across his presidency, enabling him to respond to the panic thoughtfully and deliberately.[2] After the panic, he set the national economy on a course back to the gold standard, thereby leaving it stronger than when he took office. Grant accomplished this due to the way he approached financial problem solving, which at times put him at odds with his own Republican Party and the special interests of the day. This article uses President Grant’s writings to show what he said and did at the time, putting these in context via national debt, monetary, financial markets, and gross domestic product (GDP) data as well as supplemental secondary materials.

Several insights emerged from the research, including the realization that Grant was more financially sophisticated than many historians have acknowledged. For example, he distinguished the real economy from the financial economy, and he used that distinction to help guide his responses to the panic and its aftermath. Grant also insisted that banking executives do all in their power to resolve the panic themselves with only marginal help from the government. Significantly, Grant’s experience shows that deflation does not always equate to depressed financial returns. In sum, President Grant brought a calm and deliberate approach to financial panic/crisis management, which modern politicians, Treasury officials, central bankers, and economic advisors would do well to study.

The Civil War and National Finance

To appreciate the situation President Grant faced in 1873, one must first understand how the Civil War changed the United States’ economy. Prior to the war, the US was a confederation of individual states that governed under broad constitutional oversight. During the war the federal government aggregated the states’ military resources and funded their supply and activities, in part by expanding the national balance sheet as illustrated in figure 1.[3]

It was not just the amount of debt that was new, but also how it was sold. The task of selling the national debt was awarded to Jay Cooke, a politically well-connected banker (Larson 1936). Cooke employed a highly innovative approach to market debt directly to the public, and by so doing invented the arts of financial public relations and mass financial marketing (Davies 2018, 26; Rothbard 2002, 133). His efforts were successful and resulted in the next challenge for the US government: how to service the debt.

Massive amounts of debt can be difficult to timely service, especially with a specie monetary base, which was standard in the nineteenth century. Heavily indebted governments can therefore feel “forced to suspend specie payments and issue paper money” (Davies 2018, 3).[4] The US government generally did this, although tariffs remained payable in gold, as did the bonds that were payable in gold (see footnote 3). First, in 1862, the government issued United States Notes (US Notes, or greenbacks) (Greenberg 2020, 163–68; Unger 1964; Mitchell 1903), which “were made legal tender for all debts, public and private, except that the Treasury continued its legal obligation of paying the interest on its outstanding public debt in specie” (Rothbard 2002, 123). Congress then passed the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864, which, among other things, resulted in the issuance of National Bank Notes (Greenberg 2020, 167–69; Rothbard 2002, 132–47; Willis and Edwards 1922, 406–12).[5] Figure 2 compares US Notes and National Bank Notes to the total currency in circulation, or monetary base, over time.

The monetary base more than doubled from 1860 to 1865 (compounding at 20 percent). By 1865, US Notes and National Bank Notes comprised 48.5 percent of the monetary base, increasing to 81.9 percent in 1869 (figure 2), and thus “the legal-tender acts led to a substitution of paper for a specie circulation” (Mitchell 1897, 125). This troubled Grant, for as he stated in his December 6, 1869, annual message: “Among the evils growing out of the rebellion . . . is that of an irredeemable currency” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 20, 21). Evil or not, fiat currencies helped to fund a dramatically different economy than the one that came before.

Postwar Boom

As the US was no longer on the gold standard the financial industry was able to significantly expand credit, which is reflected in the growth of the monetary aggregates at the time (figure 3). From 1867 to 1873, M2 grew at a compounded rate of 4.0 percent while M3 grew by 6.5 percent (calculations are rounded).[6] As credit was no longer needed to fund the military, inflationary finance shifted to industrial production, which included railroads (see the annual index of US industrial production for 1790–1915 in Davis 2004). Significantly, “credit expansion always generates the business cycle process, even when other tendencies cloak its working” (Rothbard 2009, 1003); this occurred after the Civil War as demilitarization, Reconstruction, and industrialization combined to generate a great deal of economic activity that was financed by a credit-fueled investment boom. Then, as now, technological innovation can offer lucrative investment opportunities, especially during a boom. And then, as now, governmental grants/funding/guarantees can misdirect investment into channels that private investors would not otherwise pursue.[7]

In the late nineteenth century the leading technological innovation was railroads, the development of which was facilitated by governmental land grants, loans, and guarantees (e.g., Newman 2014, 484). While “investment in railroads virtually ceased during the Civil War,” according to Hannah Catherine Davies (2018, 4), it “picked up rapidly in the second half of the decade, not least thanks to western expansion and the construction of the first transcontinental railroads. Between 1868 and 1873, an additional 29,589 miles of railroads were built.”[8]

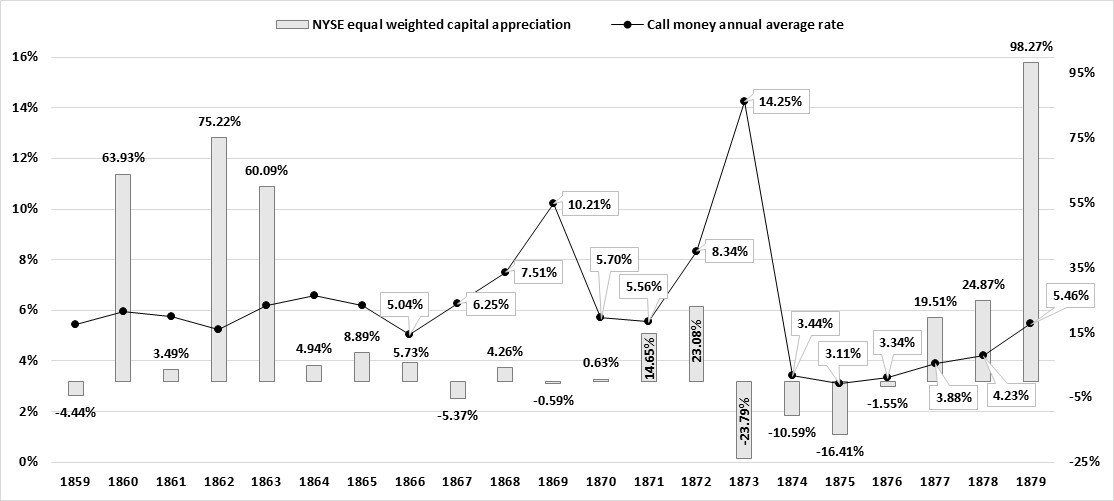

Speculative activity concentrated in railroads but spread across the economy. While nineteenth-century financial market data is sparse, it is available, and so is the data on speculative stock market funding rates, known as “call rates” because creditors can call the loans secured by financial securities on demand (Willis and Edwards 1922, 191–92). By way of background, “The national banking system created three sets of national banks: central reserve city, which was only New York; reserve city, other cities with over 500,000 population; and country, which included all other national banks” (Rothbard 2002, 136; italics original; see also Wilson, Sylla, and Jones 1990, 88–89). When country banks had excess reserves—due to seasonal agricultural requirements, for example—they sent those reserves to reserve city banks (or in some cases directly to central reserve city banks) to earn interest. “Hence,” President Grant observed in a letter to the US Senate, “they cease to have the character of reserves because they must be loaned to earn . . . interest and a profit. Being subject to ‘call,’ all loans from this reserve must necessarily be ‘call’ loans. Legitimate business cannot be transacted with Capital borrowed on these terms” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 25, 66).[9] This observation was correct, but it would come later, on April 22, 1874; for now, it is important to understand that call money funded stock market speculation in the mid to late 1800s similarly to the way junk bonds funded leveraged buyouts in the 1980s.[10] Figure 4 plots stock market return and call money rate data from the time.

Grant, National Finance, and Financial Speculation

Despite the investment boom, when Ulysses S. Grant became president on March 4, 1869, the nation’s finances were under pressure. Consider the national debt: after 1866,[11] it declined every year until 1874, as figure 1 illustrates. Additionally, the monetary base topped at $1.083 billion in 1865 and then declined to $740.641 million in 1869, which was the postwar low, as illustrated in figure 2 (a compounded decline of 9.1 percent). Grant therefore inherited a contracting national balance sheet and a contracting monetary base, but, significantly, the monetary base did not contract to prewar levels. Despite being the postwar low, the 1869 monetary base was still 70.1 percent greater than the 1860 monetary base of $435.407 million (figure 2). Additionally, US Notes and National Bank Notes comprised 81.9 percent of the monetary base in 1869 (figure 2), which concerned Grant, as noted above, and enabled the credit expansion that fueled the investment boom (figure 3).

One consequence of investment booms is speculative activity, which Grant had to contend with in both of his presidential terms. The preeminent speculator during Grant’s presidency was Jay Gould. Part speculator, part investor, and part businessman, Gould can be thought of as a modern-day hybrid of speculator George Soros and Apollo Capital Management. In 1869, the first year of Grant’s presidency, Gould’s railroad investments were heavily leveraged and under pressure given the contracting economy,[12] low-to-negative stock market returns from 1866 to 1868 (figure 4), and rising cost of debt (e.g., the 49 percent rise in call money rates from 5.04 percent in 1866 to 7.51 percent in 1868 [figure 4]). In assessing this, Gould reasoned that if he could increase the price of gold through a corner, it would increase the value of his investments and benefit the farmers who used the railroads to transport their goods, as well as the merchants who sold those goods.

According to Maury Klein (1986, 102), “It was surprisingly easy to corner the available supply of gold in New York. The amount, usually ranging between $15 million and $20 million, could be purchased on credit with a modest investment and then loaned to merchants who were short.” This was, however, risky, as the government could break a corner by selling some of its gold holdings; however, if it could be convinced not to do that a corner could succeed. Gould accordingly met with Grant personally, tried to bribe his private secretary, General Horace Porter, and lobbied his brother-in-law, Abel R. Corbin, for favorable gold policy, which included the recruitment of General Daniel Butterfield, the new head of the New York subtreasury (Klein 1986, 99–115). None of this worked.

The story of how the gold corner was crushed has been told elsewhere (e.g., Klein 1986, 99–115); however, it is generally not appreciated how well President Grant understood the financial dynamics surrounding the attempted corner. For example, on September 12, 1869, as gold prices became volatile due to Gould’s trading, Grant wrote his Treasury secretary at the time, George Boutwell, prior to the secretary’s trip to New York:

On your arrival you will be met by the bulls and bears of Wall Street, and probably by merchants too, to induce you to sell gold, or pay the November interest in advance, on the one side, and to hold fast on the other. The fact is, a desperate struggle is now taking place, and each party wants the government to help them out. I write this letter to advise you of what I think you may expect, to put you on your guard.

I think, from the lights before me, I would move on, without change, until the present struggle is over. (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 19, 244; italics added)

Grant did not bail anyone out, including his brother-in-law, which was consistent with the way he approached national finance in general; namely, by focusing on the real economy without regard to the consequences to speculative finance or any special interest, including partisan politics.

Differentiating the real economy from the financial economy is a modern distinction, which raises the question of what President Grant’s economic/financial philosophy was and how he formed it. This is important because many authors have criticized Grant’s financial acumen. For example, Allan Nevins (1957, 2, 686) claims that “Grant obviously knew nothing whatever about finance,” while Irwin Unger (1964, 215) claims that Grant was financially “timid and indecisive.” This article found no evidence to support such claims with respect to the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath.[13]

Grant did not receive formal economics/financial training, and he adhered to no specific school of thought, as far as I can tell. However, he did not receive formal general officer training either, and therefore his battlefield successes resulted from the way he thought through military problems and issues in the context of the strategic situation at hand.[14] Such an approach is consistent with the way he approached national finance, with one exception: Grant worked in the context of the orthodox economic thinking of the time, which was generally conservative, holding “a limited role to government. Most mainline politicians thought its principle responsibility in managing the money supply was to ensure a ‘sound’ currency and otherwise keep its hands off” (Calhoun 2017, 419).

There were two principal ways to manage the money supply at the time—a hard-money, specie-based approach and a soft-money, inflation-based approach—which did not divide by party lines. In fact, “the Democrats had a far greater proportion of congressmen devoted to hard money and to resumption than did the Republicans” (Rothbard 2002, 151). If there was a divide in the two approaches it appears to have been regional, as congressmen “from the West and South generally favored inflation [soft money], and those from the Northeast opposed it” (Calhoun 2017, 440). A further division was that those who heavily used or depended on abundant cheap credit—such as railroad, steel, labor, and agricultural businessmen—favored soft money, while those who used credit conservatively or intermediated specie transactions—such as conservative businessmen and bankers—favored hard money.

Grant was a Republican president, but he thought and acted independently, similarly to the way he commanded the army during the war, which occasionally conflicted with the party line. Therefore, he sometimes ruffled political feathers, especially early in his administration, which caused him to modify his approach by exercising greater party leadership. Nevertheless, Grant’s primary decision-making objective remained to make the “right” decision as he understood it without regard to political or special-interest pressure to the contrary (e.g., Calhoun 2017; Chernow 2017; R. White 2016; Perret 1997).

Grant’s economic/financial understanding was informed by a broad network of information sources that was at least partially processed through his White House staff, a function that Grant brought with him from the army. He was the first president to employ a formal staff like this (see Calhoun 2017, 77–79). In addition, Grant actively used his cabinet to think through economic/financial issues and options. His cabinet was composed of advocates from both monetary camps: in the hard-money camp were Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, who was arguably Grant’s most capable and influential advisor (e.g., Nevins 1957, vols. 1 and 2), Postmaster General John Creswell, and Treasury Secretary William Richardson (albeit marginally). In the soft-money camp were Interior Secretary Columbus Delano, Attorney General George Williams, and Secretary of War William Belknap (Calhoun 2017, 442). In cabinet meetings Grant welcomed all viewpoints, which differed from his generalship during the war, when he used only his own judgment. Nevertheless, during his presidency Grant kept his positions to himself before a decision was made, and “reserved for himself the power to decide” (Calhoun 2017, 3).

In addition to polling his cabinet, Grant traveled broadly and spoke with a wide group of people, including the business and financial titans of his day, such as Jay Gould, Jay Cooke, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Anthony Drexel, who espoused positions from both monetary camps. Finally, it is reasonable to assume that Grant closely followed national economic/financial developments through the press. In sum, the economic/financial information that Grant received during his presidency helped to increase his knowledge of national finance, which enabled his management of the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath.[15]

Returning to the attempted gold corner: with its end call money rates declined to 5.70 percent in 1870 from 10.21 percent in 1869 (figure 4), which was facilitated by a 4.6 percent increase in the monetary base (to $774.966 million from $740.641 million), with the portion of US Notes and National Bank Notes declining to 79.2 percent from 81.9 percent (figure 2). Nevertheless, Grant remained concerned about the fiat-heavy monetary base, as this comment from his December 5, 1870, annual message reflects: “The fact cannot be denied that the instability of the value of our currency is prejudicial to our prosperity, and tends to keep prices up to the detriment of trade” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 21, 61).

The stock market posted a small gain in 1870, which erased the prior year’s small loss, followed by a 14.65 percent gain in 1871 and 23.08 percent gain in 1872 (figure 4). However, equities reflect only a snippet of what was happening at the time. For example, consider Grant’s draft annual message of December 4, 1871, which profiles developments in Reconstruction, the Territory of Utah, foreign affairs, the reduction of the national debt through a refinanced bond issue, taxes, tariffs, gold fluctuations, the army, the postal system, Indian affairs, public lands, agriculture, immigration, public corruption, and the civil service (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 22, 252–68). There was also the matter of presidential politics and reelection, which led Grant to observe the following to General William Tecumseh Sherman on January 26, 1872: “Politicians are at their usual tricks in presidential election years” (22:356). Grant’s agenda was therefore very full; nevertheless, national finance was foremost on his mind. For example, in his draft annual message of December 2, 1872, he wrote: “The preservation of our National credit is of the highest importance; next to this comes a national currency, of fixed, unvarying value as compared with gold, the standing currency of all civilized and commercial Nations” (23:296). These beliefs would be tested the following year, and the test would be triggered by the industry Grant praised in the same annual message: railroads.[16]

The Panic of 1873

The euphoria generated by the abnormal returns of a boom carries away many investors (e.g., Kindleberger and Aliber 2011). This was seen during the “new era” boom of the 1920s, the “new economy” boom of the 1990s, and the “new paradigm” boom that resulted in the 2007–8 financial crisis. The same dynamic occurred in the 1870s, which is understandable given all the change occurring at the time, including the first age of globalization, commonly dated from 1870 to 1914 (the start of World War I), and simultaneously booming financial markets in Berlin, Vienna, and New York. Many people at the time therefore knew their age “really was different”; however, such thoughts helped facilitate the speculative behavior characteristic of booms.

No one knows (or can know) when a boom will end in real time, but there tend to be clues of the coming “tipping point,” when a boom ends and reverses, and this was the case in 1873. For example: (1) In 1872, call money rates increased to 8.34 percent from 5.56 percent the year before (figure 4), reflecting increased risk levels; (2) the booms in Berlin and Vienna started to top out and reverse “in the late summer and early fall of 1872” (Kindleberger 1990, 74);[17] (3) by April 1873, the boom in the US started to slow, which extended into the summer (Carosso 1987, 180–81; R. White 2016, 541); (4) in July 1873, Brooklyn Trust “closed its doors”; and (5) on September 8, 1873, the Mercantile Warehouse and Security company failed, which was followed by (6) the failure of Kenyon, Cox and Co. on September 13 (Wicker 2006, 19).[18]

The tipping point came on September 18, 1873, with the failure of Jay Cooke’s firm. To understand how Cooke failed, recall that he was the government’s bond salesman. Therefore, after the Civil War ended he was “in search of new business opportunities” (Davies 2018, 41), which meant railroads, given their scope. Due to globalization, Cooke could seek both foreign and domestic investors, facilitated, in part, by his governmental connections, and thus he committed to finance the massive Northern Pacific Railroad even though he was “a late comer to railroad finance” (Kindleberger and Aliber 2011, 165; Kindleberger 1990, 78–79).

Given the slowing-to-distressed financial environment profiled above, Cooke was unable to place/sell significant amounts of the Northern’s bonds, which at a minimum contributed to his failure (Davies 2018, 65; Lubetkin 2006, 268–93; J. Grant 1992, 52–55; Kindleberger 1990, 79–80; Logan 1981, 75–84; Sobel 1970, 178–79; Larson 1936, chap. 19). According to Larson (1936, 410), “Under the stress of the growing reluctance of the bond buyer and increasing stringency in the money market, it proved impossible [for Cooke] to carry the load at a time when the depositors were demanding their money.” The resulting panic “was soon to engulf the entire country and spread across the Atlantic” (Davies 2018, 65). Annual call money rates spiked to 14.25 percent from 8.34 percent the year before, a 70.9 percent increase and the period high (figure 4). However, monthly call money rates ranged from a low of 3.8 percent to a high of 61.23 percent, with an “extreme quotation” of 360 percent (Homer and Sylla 2005, 315). Significantly, M2 and M3 increased from 1872 to 1873, which suggests that a general credit restriction either did not occur during the panic or occurred only briefly, as the aggregates increased again from 1873 to 1874 (figure 3).

Pleas for the government to mitigate panic-driven distress by inflating the monetary base occurred immediately. Significantly, “as in the previous decade, the industry’s trade organizations and trade publications spearheaded the soft-money drive” (Unger 1964, 222). President Grant was therefore under pressure, as industry and media barons have long donated money to, and attempted to influence, politicians. For example, on September 19, 1873—the day after Cooke’s failure—Senator Oliver Norton wrote to Grant claiming an “imminent danger of [a] General national bank panic tomorrow saturday unless” the government released its $44 million US Notes reserve (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 24, 213). Grant refused, stating in his reply of the same date, “All assistance of the govt. seems to go to people who do not need it but who avail themselves of the present depressed state of the stock market to buy dividend paying securities, thus absorbing all assistance without meeting the real wants of the country at large” (24:213). Note the distinction between people in need (the real economy) and those using governmental money to fund their investment activity (the financial economy). Nevertheless, later the same day Treasury Secretary William Richardson allocated $10 million of the reserve to buy government bonds, stating that he would “limit the amount to about twelve millions and stop there; and if all the banks suspend by agreement, I would stop at once. I don’t think it is well to undertake to furnish from the Treasury all the money that frenzied people may call for” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 24, 214).

One constant of financial panics is that excessive leverage magnifies losses (e.g., Calandro 2024), which means that adverse events can suddenly manifest, as occurred in this case, for the next day—September 20, 1873—the stock market “closed until further notice” (Nevins 1957, 2, 695–96).[19] By September 27, $14 million of the US Notes reserve was allocated to bond purchases,[20] with Grant observing on that date in a letter to Horace B. Claflin and Charles L. Anthony, “No Government efforts will avail without the active co-operation of the banks and moneyed corporations of the country” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 24, 219). This was significant, for as soon as the panic began, the New York Clearing House (NYCH) responded just as it responded to “the banking disturbances in 1860 and 1861, that is, by authorizing the issue of loan certificates and the equalization of reserves among the member banks” (Wicker 2006, 31).[21]

By way of background, the NYCH was created in 1853 by larger commercial banks to provide central bank–like services for its members. It was effective in that role, as relatively few commercial banks failed during the Panic of 1873. Most of the failures and suspensions were “among private banks or brokerage houses” (Wicker 2006, 18), which funded speculation in the call money market.[22] According to Wicker (2006, 18), there were “fewer than forty bank suspensions in the country as a whole, excluding brokerage firms.” A key reason was the equalization of reserves by the NYCH, which “enabled the seven large New York banks that held the bankers’ balances to continue to pay out cash freely to interior banks” (Wicker 2006, 31). This was significant because immediately prior to the panic, 31 percent of New York bank loans were call (or demand) loans (Wilson, Sylla, and Jones 1990, 89; Sprague 1910, 84). Therefore, through its actions the NYCH enabled “the ultra-liberal policy of continuing to pay out cash to the interior, which we do not observe in future panics” (Wicker 2006, 33; Thies 2020 discusses this in the context of the Great Depression of the 1930s) and which mitigated the effects of the Panic of 1873.[23] Consequently, it may be asked: What did President Grant do (with congressional support)?

First, he monitored developments intensively via his broad information network mentioned above, which enabled him to take measured action at the margin to help mitigate financial distress. Thus, by October 1, 1873, the day after the stock market reopened (Wicker 2006, 27), “the net addition to the currency by clearing-house certificates, use of government money, and other expedients was estimated at $50,000,000” (Nevins 1957, 2, 700). Figure 2 illustrates the marginal governmental portion of this: from 1872 to 1873 the monetary base increased by 1.1 percent (from $829.209 million to $838.252 million), and from 1873 to 1874 it increased by 3.0 percent (to $863.606 million). The percentage of the monetary base composed of US Notes and National Bank Notes increased marginally from 81.4 percent in 1872 to 82.0 percent in 1873 and 82.4 percent in 1874.[24] In today’s terms you could say that Grant “learned by doing” during the panic (Bernanke 2012), but his “doing” was only marginal, in order to mitigate the impact his actions would have on the real economy.[25]

Second, Grant kept pressure on the banking community to mitigate their industry’s distress. For example, on October 19, 1873, he responded to a letter from the president of the Metropolitan Bank in New York City by asking, “Cannot the Bank Presidents be brought together and resolve to aid each other, and the business interests generally. The government then will do all in its power” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 24, 230). Note that Grant’s wording is a request, not a question, and the request communicated his desire for banking to support the business of the real economy (in contrast with speculation in the financial economy) before the government did “all in its power.” This sequence of roles and responsibilities is fundamental to Grant’s approach to national finance.

Third, and contrary to modern practices, President Grant did not deficit spend to mitigate panic-generated distress; on the contrary, and as can be seen in figure 1, he reduced the national debt by 0.8 percent in 1873.

Finally, according to Ronald C. White (2016, 544), “Grant’s quiet leadership and steady hand, quite different from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s public cheerleading in confronting the Great Depression sixty years later, did much to calm troubled waters.”[26] And with calmer waters the Panic of 1873 ended.

This does not mean that Grant’s decisions were made effortlessly or even linearly. They were not, as there are accounts that “Grant had almost surrendered” to inflationary pleas (Nevins 1957, 2, 702–5) and that both he and the Congress tried to find a compromise between inflation (i.e., increasing the quantity of US Notes and/or National Bank Notes in circulation) and no inflation. For example, consider this paragraph from Grant’s December 1, 1873, draft annual message:

My own judgement is, that however much individuals may have suffered one long step has been taken towards specie payments; that we can never have permanent prosperity until a specie basis is reached. . . . To increase our exports sufficient currency is required to keep all the industries of the country employed. Without this National as well as individual bankruptcy must ensue. Undue inflation on the other hand, while it might give temporary relief, would only lead to inflation of prices, the impossibility of competing in our own markets for the products of home skill and labor, and repeated renewals of present experiences. Elasticity to our circulating medium therefore, and just enough of it to transact the legitimate business of the country,[27] and keep all industries employed, is what is most to be desired.[28] The exact thing is specie, the recognized medium of exchange the world over. (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 24, 262–63)

Grant is clearly struggling with “the money question” here, but, significantly, he did not panic and overreact to it as so many national leaders have during modern financial panics/crises.[29] Conversely, he monitored and analyzed financial developments carefully before taking marginal action,[30] which ultimately led to his rejection of inflationary policies. Grant’s decision-making process was likely similar to the one he used as a general officer, as noted above: keeping the desired end state firmly in mind, consistently collecting and evaluating all relevant information, and deriving appropriate strategies to realize the end state as quickly as possible, regardless of special interest or political pressure to the contrary.[31] This may sound simple, but it is not, which is why so few leaders in the military, the Treasury, central banking, and the presidency have been able to replicate it.

Even though the panic ended, the economy remained volatile; for example, the stock market closed the year down 23.79 percent (figure 4). Therefore, pleas for the government to help by inflating the monetary base continued.

The Currency (or Inflation) Bill of 1874

Following the financial crisis of 2007–8, the Federal Reserve continued its inflationary strategy—quantitative easing—for another dozen years, resulting in consequences that, some feel, left financial services firms “vulnerable—just as they were during the mortgage boom” (Leonard 2022, inside flap). While the Fed undertook many new initiatives after the crisis, its objective—inflate the currency post panic to stimulate economic activity—was not new. Grant was pressured to do the same thing after the Panic of 1873; the pressure coalesced in the Currency Bill (Senate Bill No. 617), which would have significantly increased the monetary base. The bill passed both houses of Congress, and, significantly, “in the House [of Representatives it passed] by a Republican vote of 105–64, while the Democrats voted against by the narrow margin of 35–37” (Rothbard 2002, 151). Thus, on April 14, 1874, the Currency Bill was sent to Grant for his signature with the endorsement of his party.

Given the politics of the Currency Bill, also referred to as the Inflation Bill, Grant considered it carefully, and then decided to veto it despite the endorsement of his party. His veto is consistent with the above comments pertaining to Grant making the right decision as he understood it without regard to special interests or partisan politics. He announced the veto in a cabinet meeting on April 21, 1874, and followed up with a written explanation to Congress the next day (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 25, 73–75).

As Grant was considering the bill, he characteristically kept his thoughts to himself, which seems to have caused both backers and detractors of the bill to feel he was on their side. This practice of Grant’s is possibly a reason why some people have given others credit for Grant’s achievements.[32] That error seems to have reversed in the military arena, but it should also reverse when it comes to national finance. For example, consider the description by Grant’s well-regarded secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, of Grant’s approach to the Currency Bill:

You must give the President the undivided credit for what he did. Never did a man more conscientiously reach his conclusions than he did in the matter of that bill, and this in the face of the very strongest and most persistent influences brought to bear upon him; and you can scarce imagine the extent and the variety of the sources which were drained to influence him; and now that he has decided, many who were very urgent to persuade him to an opposite course from that which he took, are either silent or professedly in approbation. He has a wonderful amount of good sense,[33] and when left alone is very apt to follow it, and to “fight it out on that line.”[34] He did so in the recent matter, and astounded some who thought they had captured him. (Nevins 1957, 2, 714; italics original)

The “very urgent” pressure on Grant to inflate the monetary base was intense,[35] which is likely a reason why 1874 is the only year of his presidency when the national debt increased, albeit marginally at 0.8 percent (figure 1). Adding to the pressure, Grant’s Treasury secretary was implicated in a fraudulent scheme, which led to the secretary’s resignation (Nevins 1957, 2, 714–15).[36] Grant famously supported Secretary Richardson, as he was a loyal president (and general) who trusted and supported the people who worked for him, some of whom were not worthy of it.[37] Such an approach resulted in a terrible cost to Grant after his presidency, when he was defrauded by a business partner, leading to his financial ruin (Ward 2012; J. Grant 1992, 60–61; Wilson, Sylla, and Jones 1990, 90–91) and the eventual decision to write his Civil War memoirs (Flood 2011, 1–54; Perry 2004, 219–35). Effective modern leaders who employ Grant’s approach intensely monitor their subordinates to ensure that their performance proceeds as expected, and if it does not, they will quickly intervene.

The Specie Resumption Act of 1875

Monetary affairs remained foremost on Grant’s mind following his veto. A reason for this was likely the composition of the monetary base. In 1873, US Notes and National Bank Notes represented 82.0 percent of the monetary base, which increased to 82.4 percent in 1874 and would increase to 82.8 percent in 1875, which was the period high both for this measure (figure 2) and for the monetary aggregates (figure 3). This concerned Grant and led him to make this important observation on June 1, 1874: “There is no question in my mind as to the fact that the poorer currency always will drive the better out of circulation” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 25, 116; italics original). This is Gresham’s law (Guy 2019), and points to an atypical level of national financial understanding for a president.[38] For example, consider President John F. Kennedy’s complaint to advisor Ted Sorensen “that he had trouble distinguishing between the meaning of the words ‘monetary’ and ‘fiscal’” (Alsop 1968, 259).[39]

Grant also understood that fiat currency could lead to credit expansion that “begat a spirit of speculation—(the currency being of fluctuating value . . . [naturally became a subject of speculation in itself] . . .)—involving an extravagance and luxury not required for the happiness or prosperity of a people, and involving, both directly and indirectly, foreign indebtedness” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 25, 272).[40] This statement from his draft annual message is significant for two reasons. First, it once again shows Grant’s ability to differentiate speculative finance from the real economy. Second, it was written on December 7, 1874, and as noted above, 1874 was the only year of Grant’s presidency when the national debt increased (figure 1).

It is easy to incur excessive levels of debt, and therefore it is politically difficult to reverse course, even marginally. Nevertheless, that is what Grant did with congressional support. First, he reduced the national debt in seven of the eight years of his presidency (figure 1). Second, he responded to the Panic of 1873 at the monetary margin and indirectly via pressure on the banking industry. Third, he vetoed the Currency Bill. And then he decided the time had come to return to the gold standard. As Grant explained in his draft annual message of December 7, 1874: “Gold and Silver are now the recognized mediums of exchange the civilized world over; and to this we should return with the least practicable delay. In view of the pledges of the American Congress when our present Legal Tender system was adopted and debt contracted there should be no delay—certainly no unnecessary delays—in fixing, by legislation, a method by which we will return to a specie” (25:272).

At this point Grant no longer considered inflationary arguments, because such “propositions are too absurd to be entertained for a moment by thinking or honest people” (25:273). He wrote those words in the same draft annual message of December 7, 1874, and followed up the next month (on January 14, 1875) by signing the Specie Resumption Act (Senate Finance Bill No. 1044), “which fixes a date when specie resumption shall commence” (26:35).[41] In the same document Grant sought to raise revenue (through tariffs and customs duties) to pay down the national debt (26:35–36), which would fall by 0.9 percent in 1875, thereby exceeding the prior year’s marginal increase (figure 1). Significantly, as table 1 shows, the monetary aggregates declined for the next three years (except for M3 in 1876, which was unchanged from the prior year).

Monetary deflation over the intermediate term was required before the prosperity expected to be generated from the gold standard would be realized. However, it must be noted that the Specie Resumption Act was only hard money based; it was not absolute. For example, it did return the US to the gold standard but not until four years later, on January 1, 1879, when Grant was no longer in office (J. Grant 1992, 70). Also, passage of the act did not mean that US Notes and National Bank Notes would be withdrawn from circulation in 1879. Instead, gold certificates and coin would progressively come to constitute a greater portion of the monetary base over time as the fiat currencies would make up a lower portion. This is what occurred, as figure 5 illustrates.

Like most legislative efforts the Specie Resumption Act was a negotiated outcome, and thus “it was not considered a hard-money victory by contemporaries” (Rothbard 2002, 151). Significantly, it was also “not everything the president desired,” but as Calhoun (2017, 486) observes, “His advocacy [of it] marked a defeat for inflationists.”[42] The act should therefore be considered a solid step toward a specie monetary base, with President Grant leaving it to his successors—and their respective Congresses—to either finish the task or pursue inflation by some other monetary base. Bimetallism would become the adopted approach and result in the Panic of 1893 (Laughlin 1896; Reed 1993).

Conclusion[43]

The economic effects of the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath were acute; for example, the GDP deflator fell at a compounded rate of −3 percent from 1873 to 1879.[44] Additionally, the stock market fell by 23.79 percent in 1873 and by 10.59 percent in 1874 (figure 4), which is likely a reason why the Republican Party “decisively lost the 1874 congressional elections” (Barreyre 2011, 403). For example, Unger (1964, 249) cites Grant’s veto of the Currency Bill as a contributing factor to the Republicans’ defeat: “In the West, Republicans found themselves everywhere on the defensive, forced either to explain away Grant’s action [i.e., the veto] or openly repudiate the party’s leader.”

The stock market fell by another 16.41 percent in 1875 due to widespread levels of financial distress; for example, 7,740 businesses failed in 1875 compared to 5,183 failures in 1873 (Unger 1964, 265n77). Significantly, 1875 was also the year that call money rates hit a period low of 3.11 percent, driven by expansion of the monetary aggregates, as deposits, M2, and M3 all grew to their period highs in that year (figure 3).[45] The stock market fell again (by 1.55 percent) in 1876, which was the final full year of Grant’s presidency. Figure 4 illustrates the above history along with how much the stock market gained in 1877 (19.51 percent) and 1878 (24.87 percent). Significantly, those returns were generated even though the monetary aggregates declined in both of those years (table 1); thus, deflation does not always negatively impact financial returns.

The impact of Grant’s actions was not just financial, as real GDP grew at a compounded rate of 2.8 percent from 1873 to 1878,[46] which was the result Grant sought to achieve. Over the longer term the economic impacts were stronger. For example, it was previously noted that the first age of globalization dates from 1870 to 1914. According to David A. Stockman (2024, 167), those years also marked “America’s greatest period of growth and wealth creation.” This is confirmed by the data, as real GDP grew at a compounded rate of 3.4 percent from 1873 to 1914 with the population growing at a compounded rate of 2.1 percent and a GDP deflator of 0.1 percent.[47]

President Grant’s administration—with congressional support—established the financial foundation of this period, which was built on three major achievements: (1) reducing the national debt by 17.7 percent (the sum of changes from 1869 to 1876, inclusive, from the source data for figure 1); (2) calmly and effectively leading the nation out of the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath without either radical monetary inflation or deficit spending; and (3) setting the US economy on a course back to the gold standard and a more specie-based monetary base.

Despite its successes, both real and financial, Grant’s approach to financial panic/crisis management contrasts sharply with modern national financial (including monetary) policies, practices, and beliefs—including the belief that deflation must be avoided at all costs. At a minimum, given the current state of national finance in the United States and the risks it poses, Grant’s approach and the results it helped generate should be rigorously reexamined by Treasury officials, central bankers, and governmental economic advisors.

This is not to say that Grant was without fault as either a general officer or a president. No general officer or president is, or ever will be, without fault. It is meant to say that the manipulation of Grant’s image over time has, at a minimum, overemphasized his weaknesses at the expense of his strengths and accomplishments, which should be reexamined.

An anonymous reviewer helpfully asked that I give my view of the appropriate monetary policy to be pursued during a financial panic, to put my findings regarding President Grant’s response to the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath into context. Briefly, the most effective management of a financial panic in relatively modern US history is, in my opinion, the “laissez-faire by accident” approach employed by Presidents Woodrow Wilson—who was incapacitated by a stroke at the time—and Warren G. Harding following the Panic of 1921 (J. Grant 2014). However, the likelihood of a modern politician, Treasury official, central banker, or mainstream economic advisor employing such an approach is, in my opinion, zero. Ideally, financial markets should be free from outside influence before, during, and after bouts of volatility, extreme or otherwise, but that is not the marketplace we face today. Therefore, my opinion on this subject can be summarized as follows: in governmentally influenced financial markets only very minimal levels of influence should be deployed during a panic/crisis, similar to the way President Grant responded to the Panic of 1873 (e.g., note the comments of another anonymous reviewer in footnote 31 below) and the way J. P. Morgan responded to the Panic of 1907 in his unofficial central banking role (e.g., Stockman 2013, 366–67). Interestingly, of these two examples the approach that Grant deployed was the more effective. For an analysis and critique of Morgan’s approach see Wicker (2006, 83–113). In sum, this is an important point that should arguably be addressed in the narrative rather than a footnote. As I was not able to efficiently incorporate it into the paper without significantly adding to the length, I opted to address it in this footnote.

The new government bonds were priced to yield 6.73 percent in 1861 (compared to 4.92 percent in 1860), 6.00 percent in 1862, 6.00 percent in 1863, 5.00 to 5.60 percent in 1864, and 4.62 to 5.42 percent in 1865. These yields are in line with bond pricing across the time period (Homer and Sylla 2005, 283n, also 305). Significantly, “Most bond issues were assumed to be payable in [gold] coin, but the contracts were not always explicit” (Homer and Sylla 2005, 302–3n1). For example, “The federal government had contracted to redeem the interest on the wartime public debt in gold, but nothing was contracted about the repayment of principal” (Rothbard 2002, 150n138). Due to differences in securities pricing and gold pricing, “the tables of bond yields for the years 1863 to 1870 do not provide a reliable picture of long-term interest rates” (Homer and Sylla 2005, 302–3n1). Richard Roll (1972, 480) analyzed the implications of this and found that “bond prices expressed in gold terms did react appropriately to major battles such as Gettysburg and Vicksburg; but gold’s fluctuating greenback premium masked the movement of bond prices expressed in greenback terms.” Roll’s methodology, data tables, and graphs are recommended for those seeking further information. Early in the research for this article data comparing the price of greenbacks in terms of gold was obtained from the Yale School of Management (n.d.). It has since been taken down.

One anonymous reviewer inquired how the size of the US debt at the time compares to common benchmarks such as the Rogoff-Reinhart line (i.e., when national debt exceeds 90 percent of GDP, repayment is at risk). From 1859 to 1879, the low (in 1859) of the debt-to-GDP ratio in the US was 1.31 percent, while the high (in 1869) was 32.32 percent, both comfortably below 90 percent, which suggests an adequate capacity to timely service the national debt (Chantrill, n.d.). Nevertheless, US government securities were at some risk of default. For instance, early in the war the path to victory was highly uncertain (Roll 1972, 478–80), and after the assassination of President Lincoln the state of the postwar economy was also highly uncertain. For example, directly after the assassination it was unclear whether the South “might be tempted to resume the fight” (Chernow 2017, 529), and efforts at Reconstruction after the war proved so difficult that “without Grant at the head of the Republican ticket, the future of Reconstruction, and perhaps the nation, could be in jeopardy in 1868” (Simpson 1991, 219).

National Bank Notes “were United States currency banknotes issued by national banks chartered by the United States Government. The notes were usually backed by United States bonds the bank deposited with the United States Treasury. In addition, banks were required to maintain a redemption fund amounting to five percent of any outstanding note balance, in gold or ‘lawful money.’ The notes were not legal tender in general, but were satisfactory for nearly all payments to and by the federal government. National Bank Notes were retired as a currency type by the U.S. government in the 1930s, when U.S. currency was consolidated into Federal Reserve Notes, United States Notes, and silver certificates.” (Wikipedia, s.v. “National Bank Note,” accessed April 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Bank_Note).

According to Joshua Greenberg (2020, 168), “The decision to make national bank notes lawful money without a claim of legal tender status based solely on government decree was part of the congressional strategy to move away from the greenback model and toward an integrated public/private currency solution.” Jay Cooke and his brother Henry “played a major role” in this solution (e.g., Rothbard 2002, 145).

The State Bank Notes used at the time were taxed by the federal government to facilitate adoption of the new National Banking System. The tax was 2 percent in 1864 and increased to 10 percent in 1865. As a result, State Bank Notes in circulation declined from $238.677 million in 1863 to zero in 1879 (Anderson 2003, table 1).

From 1867 to 1870, M2 grew by 1.8 percent and M3 grew by 4.6 percent, which accelerated from 1870 to 1873 to 6.3 percent for M2 and 8.5 percent for M3 (calculations are rounded).

The grants and other governmental concessions awarded to Tesla are a contemporary example: “In 2015, the Los Angeles Times added up the various subsidies, grants, incentives, environmental credits, tax breaks, and other forms of public assistance to which [Elon] Musk’s three companies have helped themselves. The sum: $4.9 billion. ‘He definitely goes where there is government money,’ the paper quoted Dan Dolev, a Jefferies analyst, as saying” (J. Grant 2016, 4).

Data on the history of “Miles of Railroad Built for United States, Miles, Annual, Not Seasonally Adjusted” are available from NBER (n.d.). The overinvestment in railroads during the investment boom is consistent with Austrian business cycle theory.

The comment on “legitimate business” is meant to differentiate the business of the real economy from speculative finance, which is a modern distinction that was nevertheless important to Grant, as this article will show.

In a leveraged buyout (LBO), “a small amount of equity is combined with a large level of debt to buy a company” (Platt 1994, 50). Given the leverage of LBOs, the bonds issued to finance them are high yielding and popularly known as “junk bonds.” Over- and malinvestment in junk bonds resulted in the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s to early 1990s (e.g., Mayer 1990).

The Contraction Act, passed in 1866, sought to lower prices in preparation for a return to the gold standard. It faced resistance “both in Congress and among important sectors of the public” (Unger 1964, 43) and was repealed in 1868.

“The Government’s financial recklessness was readily imitated by the community at large; debt was the order of the day in the affairs of both” (Noyes 1909, 18).

This is not a financial study of Grant’s entire presidency, which is a worthy topic of research. For example, while the progression of Grant’s financial expertise during his presidency is commented on in this article, his management of the national debt and fiscal policy deserve further analysis.

Grant explains this exceedingly well in his Personal Memoirs, which were published shortly after his death by Mark Twain in two volumes (Flood 2011; Perry 2004).

An anonymous reviewer noted that other authors such as Rothbard (2002) and Unger (1964) portray Grant as financially muddled and vacillating. I found no evidence to support such claims. The same reviewer noted that Unger (1964) claims that early in Grant’s administration the secretary of the Treasury at the time, George Boutwell, abandoned his predecessor’s policy of contracting the supply of greenbacks and postponed the resumption of specie payments (i.e., he was “increasingly unfriendly to specie payments”) (163–64). Focusing solely on US Notes (or greenbacks), a case can be made for statements like this given the following circulation profile of these notes: in the year 1867, $319.438 million in US Notes circulated; in 1868, $328.572 million; in 1869, $314.767 million; in 1870, $324.963 million; and in 1871, $343.069 million (Anderson 2003, table 1). However, such a focus ignores the impact of National Bank Notes, which were officially indirect federal liabilities but were nonetheless a driver of the increase in the money supply from 1867 to 1868 (figure 3), which was prior to Grant’s presidency. Also, the monetary nature of National Bank Notes is likely a reason why, in the 1930s, they were directly consolidated into the national currency (footnote 5 above). Figure 2 therefore combines US Notes and National Bank Notes to reflect the broader fiat monetary base, which increased under Grant’s predecessor: in 1865, US Notes and National Bank Notes represented 48.5 percent of the monetary base; this share grew to 81.9 percent in 1869 when Grant became president. In dollars, the two fiat currencies grew from $525.055 million in 1865 to $606.517 million in 1869 (Anderson 2003, table 1; calculations are mine and have been rounded).

Regarding specie resumption, ideally Grant would have moved toward it earlier, but he did not. Instead, he appointed pro-greenback Republican judges following the Hepburn v. Griswold ruling (Calhoun 2017, 119–23; Rothbard 2002, 152–53). The reasons for this include: (1) Grant’s newness to the presidency and corresponding desire not to rock the economic boat as he was coming up to speed on national finance (e.g., Grant wrote in his first inaugural address of March 4, 1869, that specie should be resumed “as soon as it can be accomplished without material detriment to the debtor class, or to the country at large” [U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 19, 140]); and (2) his focus on Reconstruction at the beginning of his presidency (see Simpson 1991 for background information on Grant and Reconstruction leading up to his presidency). As his presidency developed, Grant became much more knowledgeable about national finance and the significance of specie, as this article shows with respect to the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath, including Grant’s veto of the Currency Bill in 1874 and his sponsorship of the Specie Resumption Act of 1875 contrary to the wishes of his party, as explained below.

“The extension of rail-roads, by private enterprise, during the last few years, to meet the growing demands of producers, has been enormous, and reflects much credit upon the enterprise of the capitalist and managers engaged in it” (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 23, 297).

Charles P. Kindleberger (1990, 69) begins with the observation that his chapter on the Panic of 1873, “might properly be called ‘The Panics of 1873,’ since there were panics in Vienna and Berlin, as well as New York.” Davies (2018) extends this with an analysis of “Globalization and the Panics of 1873,” which is the subtitle of her book.

Kindleberger and Robert Z. Aliber (2011, 165–66) and Kindleberger (1990, 71–74) profile international finance clues and connections. Most people ignore financial market clues—domestic and foreign—in both Grant’s time and our time, and thus “few noticed the financial clouds appearing in the skies in 1873” (R. White 2016, 541). Significantly, one of the few who both noticed the clues and acted on them prior to the Panic of 1873 was a young J. P. Morgan (Carosso 1987, 181). On the other hand, the monetary aggregates did not contract prior to the panic as Austrian business cycle theory postulates, but instead grew as figure 3 illustrates. The drivers of and reasons for this are a topic for further research.

“The NYCHA [New York Clearing House Association] was acting in the interests of its member banks when check certification was suspended during the Panic of 1873 and the NYSE closed to trading for nine trading days from Sept. 20 to Sept. 30, 1873” (McSherry and Wilson 2013, 18). This was a mistake, as it “exacerbated the amount of hoarding” following the panic (Wicker 2006, 33).

$14 million is 1.69 percent of the 1872 monetary base of $829.209 million and 1.67 percent of the 1873 monetary base of $838.252 million (figure 2; calculations are mine and are rounded).

See Gorton and Tallman (2016, 87) for an illustration of the currency premium during the Panic of 1873 prior to the issuance of clearinghouse certificates. Thanks to an anonymous referee for this reference.

Elmus Wicker (2006, 22) explains that “by the time the panic had moderated, over fifty brokerage houses had failed in New York and Philadelphia. The collapse of so many brokerage firms was directly or indirectly connected with the stock market panic, but on a deeper level involvement in the financing of railroad construction was at the root of the problem.”

A simple, high-level example illustrates this dynamic: the NYCH issued loan certificates to, and equalized the reserves of, the central reserve city banks of New York, enabling them to pay out cash freely to reserve city banks, which, in turn, paid out cash freely to country banks.

Both M2 and M3 grew during this time (figure 3), and therefore the effects of the panic were not exacerbated by credit contraction.

Grant seems to have understood, as Lenin and Keynes apparently came to understand, the risk monetary inflation poses: “Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose” (Keynes 1920, 236).

See Badaracco (2002) for information on quiet leadership in general.

Note the focus on the real economy via “the legitimate business of the country” phrase, which is consistent with Grant’s approach to national finance, as indicated above.

An anonymous reviewer noted that Unger (1964, 214–16) characterizes Grant as sympathetic to businessmen’s pleas for inflation in 1873, which is true: Grant was very sympathetic to real economy distress caused by the financial panic, and as such he considered a broad array of potential solutions to help mitigate that distress.

Many of the books on the 2007–8 financial crisis (e.g., Sorkin 2009) describe this dynamic.

One of those actions pertained to changes in the bankruptcy code, which Congress supported (Calhoun 2017, 438).

Fuller (1977, 142, 221) provides various military examples. An anonymous reviewer summed up President Grant’s management of the Panic of 1873 by referencing his “famous willingness to fight during the war, even at significant cost, provided this advanced winning the war. And, I think that strength of leadership is reflected in his approach to money. He was willing to accept some disruption of the economy, provided a ‘secondary deflation’ did not break out and collapse the economy.”

For example, Dan Rottenberg (2001, 116, 218n) claims that Grant’s veto was due to the counsel of banker Anthony J. Drexel. I not only could find no corroboration of this claim, but Mr. Drexel’s May 9, 1874, letter to President Grant following the veto makes no such claim or even reference (U. S. Grant 1967–2009, 25, 80–81). Furthermore, Drexel is not even mentioned by Nevins (1957, vol. 2). Nevertheless, Drexel was one of the business titans of the day whom Grant spoke and interacted with, as noted above.

Note Fuller (1977, 184–87), which is titled “Grant’s Common Sense.” I believe both Fish and Fuller are referring to Grant’s ability to consistently think, act, and write/communicate clearly, which is very uncommon in both Grant’s time and ours. As Fuller (1977, 215) later observes, “Few generals have been so clear-sighted as Grant.”

This is a reference to General Grant’s famous May 11, 1864, letter to President Lincoln in which he stated, “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer” (Fuller 1977, 248).

As Unger (1964, 222) observes, quoting a 1874 newspaper report: “The strongest influence at work in Washington upon the currency proceeded from the railroads. . . . The great inflationists after all, are the great trunk railroads,” as they were all heavily leveraged.

“Grant’s legislative influence in the currency fight was all the more impressive given that during much of the session, [Treasury Secretary William] Richardson stood under a cloud of scandal” (Calhoun 2017, 446).

Fuller (1977, 298–99) provides a military rationale for this. Briefly, by overlooking subordinate mistakes Grant was able to maintain focus on the next action. This was important because Grant was always moving forward, and he frequently had to do that with underqualified subordinates. He therefore learned to work with what he had without complaint.

Dwight Eisenhower—another successful wartime general turned president—showed a similar level of national financial expertise, e.g., Stockman (2013, chap. 11), which is titled “Eisenhower’s Defense Minimum and the Last Age of Fiscal Rectitude,” and McClenahan and Becker (2011). Thanks to Pat McKim for many discussions on the five successful generals who became president: Washington, Jackson, Taylor, Grant, and Eisenhower.

President Richard Nixon once said that the American economy was so strong “it would take a genius to wreck it” (Herbers 1973). To say statements like this are incorrect would be an understatement.

This statement was based on and/or informed by Grant’s observations of (1) the Civil War and its financing, (2) the postwar boom, (3) the Panic of 1873, and (4) the panic’s aftermath. It thereby links “the depression of 1873 with inflation and credit expansion” (Rothbard 2010, 141).

As Calhoun (2017, 485) observes, consistent with footnote 15 above, “Grant’s prominent role in the passage of the Specie Resumption Act marked the progression in his thinking on the money question since the Panic of 1873.” Nevins (1957, 2, 716) concludes that “in after years men were to remember the veto of the inflation measure (followed as it was in 1875 by a Specie Resumption Act) as standing next to the Treaty of Washington among the Administration’s achievements.”

The quote continues, “and helped shift the Republican Party’s center of gravity toward the hard-money side.” As noted above, the Republican Party was not for hard money.

Thanks to Professor Dick Sylla for his helpful comments and suggestions on this section.

Index 2017 = 100. The data source is Johnston and Williamson (n.d.); calculations are mine and have been rounded.

In 1875, deposits grew by 6.3 percent, M2 grew by 4.2 percent, and M3 grew by 5.4 percent, as table 1 shows.

The source for real GDP and population data is Johnston and Williamson (n.d.). All calculations are mine and have been rounded. The resulting analysis is consistent with Newman (2014).

This is not meant to suggest that this time period was issue-free and not subject to unrest. According to Alexander Dana Noyes (1909, 1–2): “It was with the close of the Civil War that financial America became an influence of great importance in world-finance; it was as a sequel to the Civil War that many of the problems with which the country is still [as of 1909] wrestling—economic, fiscal, and social—had their origin.”

.jpeg)

.jpeg)