Mere coincidence explains why David Cass and Karl Shell (1983) adopted the term “sunspots” to mean “extrinsic uncertainty” in their paper “Do Sunspots Matter?” Shell latched onto the term after a conversation with a colleague who was studying William Stanley Jevons, and admitted to using it as early as 1977 for “storytelling” purposes (Cherrier and Saïdi 2018). In the late nineteenth century, Jevons attempted to explain that business cycles and panics were caused by the agricultural consequences of the fluctuations in the number of spots on the sun.[1] Why did Cass and Shell’s use of the term “sunspots” achieve permanence, such that today the term is used in economics to refer to uncertainty, Keynesian “‘animal spirits,’ and ‘market psychology’” (Cass and Shell 1983, 193)?

The present article seeks to answer this question by connecting the early market psychology ideas of John Mills and William Stanley Jevons to John Maynard Keynes’s (1964) use of psychology to explain the trade cycle in his The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, published in 1936. I argue that a close reading of John Mills’s (1867) “On Credit Cycles and the Origin of Commercial Panics” reveals more alignment with Austrian business cycle theory than with Keynes’s cycle theory and that Mills’s influence on Keynes’s cycle theory via William Stanley Jevons’s “sunspot theory” is based on a misinterpretation of Mills.

Jevons searched for a common cause of the changing “commercial moods” that Mills (1867) had identified as a central part of his credit cycle explanation. Where Jevons was unsatisfied with the lack of explanation for changing commercial moods, Keynes (1964, 161) was content to leave them unexplained: “Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive . . . can only be taken as a result of animal spirits of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.” Keynes explicitly rejected any conscious cause of this “spontaneous urge,” downplaying the extent of calculated action. Even though Keynes used the term “animal spirits” only three times in The General Theory, the idea of spontaneous fluctuations in market participants’ moods is a central theme. Keynes (1964) applied Jevons’s cycle theory to his own in The General Theory, and we see him appreciate the psychological elements of Jevons’s cycle theory in his biographical essay on Jevons (Keynes 1936). This means that, to the extent that Keynes was influenced by Jevons’s sunspot papers, John Mills’s use of market psychology found its way into Keynes’s theory.

It is well established in the history of economic thought literature that Keynes was influenced by other Cambridge economists—especially Alfred Marshall and A. C. Pigou—but the influence of Mills via Jevons is not well established. Figure 1 shows who influenced whom regarding the element of market psychology in the business cycle.

The present article primarily discusses the bottom row of influence, from Mills through Jevons to Keynes, with the caveat that neither Jevons nor Keynes appreciated the proto-Austrian elements of Mills’s credit cycle theory.

The Early Development of the Role of Market Psychology in Business Cycles

Jevons accepted “without modification” Mills’s “commercial mood” (Peart 1991, 244) explanation of the cycle, but sought a common factor that could explain the changes in market psychology and the periodicity of the cycles. According to Peart (244), “Much of the groundwork for Jevons’s explanation of economic fluctuations had been prepared by Mills. . . . Jevons’s earliest analysis of fluctuations has much in common with the position taken by Mills, who relied in turn upon J. S. Mill’s Principles of Political Economy.”

Peart (1991) summarizes the development of the influence of market psychology in economic cycles in Mill, Mills, and Jevons. John Mills (1867, 21, 32) cites John Stuart Mill in his “On Credit Cycles and the Origin of Commercial Panics,” and the two corresponded about monetary policy (Peart 1991, 244n3). Thus, whatever Keynes gleaned from Jevons’s business cycle contributions finds its origin in John Stuart Mill[2] and, more fully, in John Mills. As pointed out by Peart (1991, 245), Mill’s (1909, 527) Principles of Political Economy, first published in 1848, notes that “some accident” like the opening of trade in a new region or “simultaneous indications of a short supply of several great articles of commerce” can set in motion altered expectations of prices and can therefore induce speculation “in several leading departments at once.” Mill “stressed the role of speculation and altering investors’ expectations in the cycle, but left the explanation for these alterations largely unspecified” (Peart 1991).[3] Mill suggested that a fall in profits encourages speculation in projects with higher risk (Peart 1991, 145), whereas Mills suggested the opposite. According to Mills (1867, 25), better business conditions in the present convince entrepreneurs that the future will be just as bright: “We know the tendency of the human mind to take from present conditions the hues of a forecasted future.”

John Mills’s “On Credit Cycles and the Origin of Commercial Panics”

John Mills’s (1867, 13–14) “On Credit Cycles, and the Origin of Commercial Panics” traces the phases of the business cycle and takes as given a ten-year period for the cycle, based on an apparent regularity of the data: “The first and most suggestive feature of these events, then, is the striking uniformity in the periods of their occurrence. . . . It is an unquestionable fact that about every ten years there occurs a vast and sudden increase of demand in the loan market, followed by a great revulsion and a temporary destruction of credit.”

Later, Jevons would go to great lengths in explaining the correlation of the periodicity of the economic cycle with that of the number of sunspots. Mills (1867), however, was concerned less about the ten-year period than about the changes in commercial moods, credit, and speculation throughout the phases of the cycle. Near the end of his essay, Mills (25–27) identifies a mismatch between real savings and the supply of credit as the fundamental cause of overspeculation and changes in investor attitudes.

Mills’s (1867) credit cycle theory has not received much attention, but the limited literature on it mischaracterizes his argument (Peart 1991; Glasner 2013). When describing the phases of the cycle, Mills does refer to changes in market psychology, but near the end he discusses that the unhealthy growth of overoptimistic speculation owes its origin to inflated credit. Credit is overinflated, according to Mills, when it does not match the supply of real savings. Mills, therefore, has given one of the earliest descriptions of what would later be called “Austrian business cycle theory.” Market psychology is an important feature in his description of each phase, however: “In the course of our investigation, then, we shall probably find that the malady of commercial crisis is not, in essence, a matter of the purse but of the mind” (Mills 1867, 17; emphasis in original).

Mills (1867) puts the phases in the following sequence: the “Panic Period,” the “Post-Panic Period,” the “Middle or Revival Period,” and the “Speculative Period,” which gives way to another “Panic Period.” Much of the content of Mills’s explanation of the credit cycle corroborates Mises’s (1953) business cycle theory, put forward in 1912. But Mills’s sequence matches the shape of the business cycle according to Keynesian theory (and Milton Friedman’s plucking model), in which a downturn comes first, as if ex nihilo, and then is resolved quickly by government intervention or slowly by the adjustment of expectations, prices, and wages over time (Garrison 1996).

One terminological issue in reading Mills’s “On Credit Cycles” is that he equates credit with the beliefs, values, and expectations of market actors:

In this sense the value of some things which appear to have intrinsic value of the most solid and immutable kind, depends really upon Credit. I have a piece of gold in my pocket; but its value is not in my pocket: it is in your minds and the minds of the whole human race. The intrinsic value of a sovereign to myself personally is so small as to be practically nil; it is greatly less than that of the loaf which can be bought with a fortieth fraction of it. But the sovereign passes from my hands, and through the hands of a thousand other persons, by virtue of a mental association with universal acceptance at a certain high rate of exchange. That belief, credo, or Credit is its value; but the mental process is so instant and absolute that we habitually regard the value as intrinsic; and for all practical purposes it may be so designated. (Mills 1867, 18–19)

Mills uses the term “Credit” to explain subjective value, but his use of the term is not consistent. He does explicitly refer to loans and the extension of loans upon bank reserves as “Credit” as well: “Banking reserves, the loan-fund on which current Credit is based, are replenished from domestic and foreign sources. The savings and floating balances of our people are drawn more largely into those reserves by an increased rate of interest” (35).

Thus, Mills uses “Credit” to refer to both subjective beliefs and loans. This does not mean that the two meanings are necessarily conflated, because Mills (1867, 35) explains that the two phenomena are linked (e.g., “the loan-fund on which current Credit is based”). This connection is uncontroversial—the willingness to extend a loan obviously depends on the lender’s expectation that the borrower will repay the loan, which may be informed by overall market conditions. But the fact that Mills uses “Credit” in two ways poses some problems when we attempt to compare his theory to the Austrian and Keynesian cycle theories, and it may explain Peart’s (1991, 1996) interpretation of Mills, discussed below in the section “On the Connection between Capital and Credit.”

The Panic Period

Mills (1867, 14) begins his description of the credit cycle with the panic period, perhaps because his audience in 1867 would easily recall such a panic in 1866: “And of what occurred in 1847, 1857, and 1866 I scarcely need remind you, as those years will be fresh in the memories of most of those who hear me.” Panics are a “destruction, in the mind, of a bundle of beliefs” (19). In a panic, capital is scarce and commercial activity contracts.[4] Mills describes a reshuffling of paper and real resources that is instigated by a spontaneous collapse in optimism, but the cause of this collapse is not explained in this section. Earlier, Mills (13) asserts that these psychological fluctuations “are yoked to nothing in the steady sequences of the material world.” Later, however, he suggests that credit expansion enables the excessive optimism that leads to an inevitable correction (25–27).

The Postpanic Period

There is a reversal, when the economy enters the postpanic period, from “scarcity” to “plethora”: a plethora of loanable funds in the bank compared to the demand for loans (Mills 1867, 19–20). Deposits flow into the bank, but the bank is reluctant to reissue loans because of the fresh memory of the panic, “and this dictates a much more rigid selection of securities, and concentrates the deposit of loanable Capital upon a few important centres” (20). The distaste for loans, according Mills (21), spreads to borrowers as well.

Mills’s observation is similar to the explanation of credit contraction in the bust phase of Austrian business cycle theory. Murray Rothbard (2000, 14–19), writing in 1972, outlines the “secondary features of depression,” including credit contraction and an increase in the demand for money. Both are the result of heightened caution by banks and individuals in the throes of a financial crisis and an economic bust, he writes. Credit contracts because banks are responding to the wave of their borrowers’ bankruptcies (14). The demand for money increases due to an expectation of decreasing prices and reluctance to begin new investments while so many existing malinvestments are liquidated (15). Joseph Salerno (2012, 22–23) also emphasizes how entrepreneurs’ loss of confidence helps explain the secondary deflation in the bust phase: “The recession will be further prolonged by the fact that entrepreneurs, after experiencing massive losses and capital write-downs, will temporarily lose confidence both in their ability to forecast future market conditions and in the reliability of monetary calculation.”

Over the course of the postpanic period, Mills (1867, 23–24) posits, optimism “germinates” and begins to grow slowly: “The old race of traders have still a vivid remembrance of a ‘black Friday’ or some other day of equally sombre hue. Time alone can steady the shattered nerves, and form a healthy cicatrice over wounds so deep.” This change in market psychology seems to have no other cause than time elapsing after the panic, with a concomitant loss of memory of the panic. Interestingly, though, Mills (24) suggests that the absence of exuberant speculation in this phase allows prices to fully reflect “actual” consumer demand: “Speculation having long ceased to forestall the markets, the actual wants of the world begin to emphasize demand, and so to tell upon prices.” While Rothbard (2000, 12) would not attribute malinvestment to speculation per se, he does discuss the process by which prices and consumption/investment proportions are adjusted according to consumer preferences in the correction phase of the cycle. Indeed, one of the better-known passages (probably the only well-known passage) from Mills’s “On Credit Cycles” foreshadows the Austrian concept of malinvestment: “As a rule, Panics do not destroy Capital; they merely reveal the extent to which it has been previously destroyed by its betrayal into hopelessly unproductive works” (18).

The Middle or Revival Period

Economic activity returns to normal in Mills’s (1867, 24) middle or revival period. Real profits increase in a sustainable way, and a healthy, optimistic commercial mood develops: “This may be considered the healthiest period of our commercial life, and that in which accumulations from real—as distinguished from merely nominal profits—attain their highest development” (24). Mills’s description is unfortunately brief: he jumps to the speculative period quickly, without much explanation as to what causes a healthy, growing economy to proceed into the unhealthy phases of the cycle. He briefly identifies three reasons why the unhealthy speculative period ensues: (1) new individuals enter business, and their only knowledge of the preceding panic is “mere myth, or at most a matter of hear-say tradition”; (2) entrepreneurs extrapolate present profitability into the future and expect good business conditions to endure; and (3) the high profits start to “overflow the usual channels of investment”—that is, all of the typical, “old-fashioned” investments become saturated, and so investors seek out investments that “promise better things” (25).

We will see in Mills’s (25–27) explanation of the next phase of the cycle, the speculative period, that he does point to overextended credit as a cause of unhealthy overspeculation. And in a paper he presented to the National Social Science Association in 1866, Mills (1866, 13) points out the danger of artificially low interest rates, which cause “an accumulation of loanable capital, which is a temptation to speculative investment.” Without these other references to Mills’s view of the impact of credit expansion, this section would represent a critical departure from the Austrian theory of the business cycle, which states that artificial booms are triggered by artificial credit expansion via fractional reserve banking or a central bank implementing expansionary monetary policy.

Business cycles are not a natural feature of the market economy. Rothbard (2000, 4), after establishing that the “Mises theory is, in fact, the economic analysis of the necessary consequences of intervention in the free market by bank credit expansion,” explains that the everyday fluctuations in business do not constitute or begin a business cycle. Profits work to encourage and reward successful anticipation of the future, and losses do the opposite, so there is no room for one (profit or loss) to disproportionately dominate the other in terms of overall business outcomes or the psychology of entrepreneurs, barring some mass psychosis event. Said another way, there is nothing in the natural workings of an unhampered market economy that would cause it to devolve into a speculative frenzy of reckless investment with economy-wide consequences like that brought on by an artificial credit expansion.[5]

Keynes’s (1936) explanation of the cause of a business cycle more closely aligns with Mills’s (1867, 24–25) explanation of the middle/revival period, but only if Mills’s later comments about credit expansion (26–27) are ignored. Keynes (1964, 317) attributes panics to a sudden collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital, which is “determined, as it is, by the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world.” The pessimism ripples through the population with negative effects for both consumption and investment spending. Keynes suggests that interest rates cannot be lowered enough to stimulate new investment spending, which leaves only expansionary fiscal policy as a potential remedy for an economy in such a predicament.

The Speculative Period

Mills (26) begins his discussion of the speculative period by noting that he does not mean the dictionary definition of “speculation,” which is hardly distinguishable from “ordinary trading,” but some extension of speculation beyond what would be “moderate and healthy” and is instead “excessive and dangerous.” Importantly, Mills finally gives “Credit” as the cause of turning good speculation into bad speculation:

And I cannot but think that the main condition in determining this difference [between “moderate and healthy” speculation and “excessive and dangerous” speculation] is the state of Credit for the time being. We have traced the progress of that element through two periods of its growth, and have noted its action in raising prices and profits. We noted also that speculation was carried to a trifling extent in the first period [panic], and only to a moderate extent in the second [postpanic]; but, if it were supposable that speculation could have been indefinitely extended in those periods, a large extension would have been much less likely to prove excessive and hurtful then, than it would in the third period [middle/revival], because at that time Credit, and with it price, was broadly based upon a mass of unengaged Capital, and there was less danger of the sudden and ruinous fall of prices which always accompanies a collapse of Credit. There was, in fact, a healthy equipoise between the two. Unfortunately, however, in the absence of adequate foresight and self-control, the tendency is for speculation to attain its most rapid growth exactly when its growth is most dangerous; that is, when Credit has become inflated out of proportion to the reserves of loanable Capital. And after this inflation has commenced, Credit and speculation act upon each other as reciprocal stimulants. Inflated Credit, by elevating prices and profits, tempts to further speculation; and speculation can only be carried on by multiplying instruments of Credit. (26–27; emphasis in original)

Thus, credit and optimistic investment in lines of production go hand in hand, though they are not always mutually reinforcing. Although Mills refers to them as “reciprocal stimulants,” his following sentence (the last one in the previous quote) shows that credit enables and encourages speculation, not the other way around.[6] Mills therefore departs from Mill on this idea. As Rothbard (2006, 251) noted, Mill held that speculation drove fluctuations in money and credit.

Mills (1867, 28) proceeds to explain how the speculative boom turns to bust. Prices must “give way” due to the “oppressive glut” of goods on the market. Mills gives the impression of a Keynesian “overheated economy” but does not use that term. Yet Mills (28) also refers to a strain on long-term projects like railway construction, and how the market value of securities issued by these enterprises is a “crucial test” that “throws a new light upon the dangerous rapidity with which Capital has been fixed in these works of postponed productiveness.” This description of malinvestment in longer lines of production is an Austrian insight. Thus, we find both Keynesian and Austrian tidbits in Mill’s credit cycle.

On the Connection between Capital and Credit

Finally, Mills (1867, 31) discusses the fundamental connection between capital and credit. Previously, Mills had assumed that credit grows as if according to “a single uncompounded law,” but now he explains that capital and credit should be directly correlated in equilibrium. The value of bills of exchange is evidenced by the realized productivity of capital. A disconnect, such that credit is extended beyond what capital has been proven to produce, is the source of the distortions Mills expounded earlier. Mills (31) states, “The ratio of the growth of Credit prescribes the ratio of the demand for Capital, and, therefore the rate of its hire.” While Mills (32) does not explicitly argue for full reserve banking,[7] it is clear that he recognizes the distortionary effects of a mismatch between real savings and credit. Mills (36) uses very Rothbardian language when he refers to a collapse in “the inverted pyramid of Credit” when an increase in the interest rate does not bring about its usual effect: attracting additional saving.

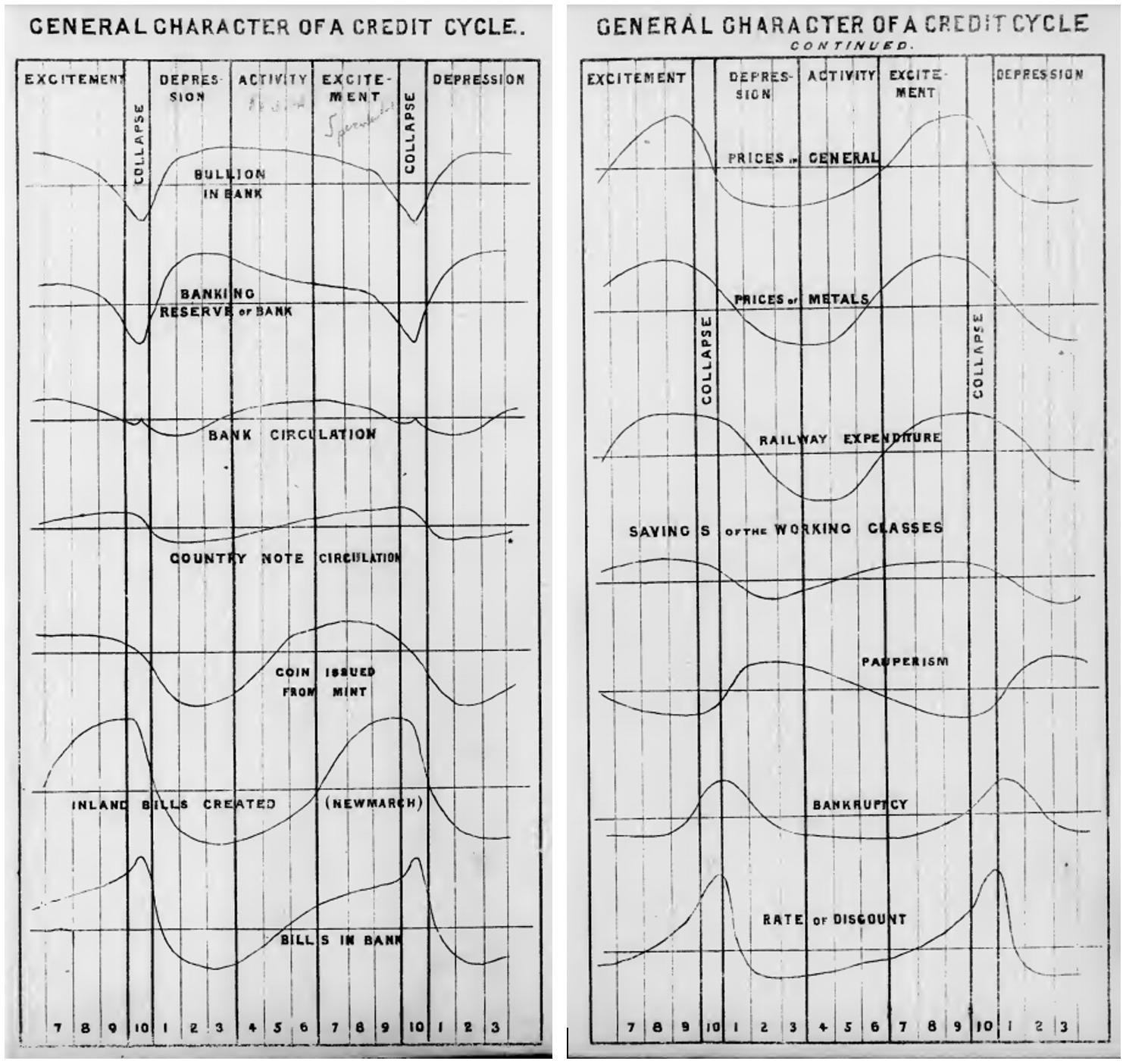

Jevons created the diagrams in Mills’s (1867) “On Credit Cycles.” Mills’s discussion of the expansion of credit beyond real savings and bank reserves is demonstrated in these diagrams, reproduced in figure 2.

Peart (1991, 1996) characterizes Mills’s “On Credit Cycles” as attributing the ultimate cause of the business cycle singularly to fluctuating commercial moods. While Mills (1867) does describe each phase as having particular changes in investors’ moods, in the end he claims that the unhealthy, overoptimistic speculation is only enabled by an inflation of credit beyond real savings. According to Peart (1996, 45), “For Mills, the cycle was characterized by ‘mental moods,’ which affected credit decisions of the lending and borrowing classes,” but, as shown above, Mills (1867, 27) actually claims the opposite: “Inflated Credit, by elevating prices and profits, tempts to further speculation; and speculation can only be carried on by multiplying instruments of Credit.” In Prices and Production, published in 1931, Hayek (2008, 277–78) notes that Mills, among other Manchester Statistical Society economists, realized the significance of excessive credit’s enabling unsustainable investment; he finds that despite their lack of standardized terminology regarding credit and capital, these economists “are of considerable interest as an expression of a fairly long and continuous strand of thought which occasionally came very near to modern ideas and in some instances leads directly to some of the best known theories of today.”

Jevons’s Sunspot Theory

Even though Jevons accepted Mills’s credit cycle “without modification” (Peart 1991, 244), he was not satisfied with the unexplained changes in commercial moods, or at least was not satisfied with Mills’s claims about credit expansion enabling overspeculation. According to Jevons (1878b, 334), “The cause can only be found in some great and wide-spread meteorological influence recurring at like periods,” namely, sunspots. Much of the volume of Jevons’s articles on the sunspot theory was devoted to establishing a correlation between crises and the ten- to eleven-year period of the sunspot cycle.

Ekelund and Hébert (2014, 381) mention the negative reception of the sunspot theory: “Jevons’s romance with statistical investigations unfortunately carried him to the most fanciful and, unfortunately, the most ridiculed idea of his life, the explanation of commercial crises on the basis of the periodic alteration of spots on the sun.” Blaug (1997, 316) also notes the negative reception: “But Jevons’ statistical case was singularly unconvincing and he failed to show theoretically how this or any other exogenous disturbance is capable of generating endogenous fluctuations.” This explains why Jevons’s sunspot theory is somewhat of a dead-end in the history of economic thought, even if Keynes and a few others appreciated the market psychology aspects. In contrast, the Austrian insight that artificial credit expansion generates booms and busts, which Mills identified and Mises and Rothbard explained more fully, is a complete and robust theory that continues to be refined and applied today.[8]

In “The Periodicity of Commercial Crises, and Its Physical Explanation,” Jevons (1878b, 335) starts with four crises that fit his expected pattern nicely: those that occurred in 1866, 1857, 1847, and 1837. The 1837 crisis was only in the United States, while the ones in England were in 1836 and 1839. Jevons marches back in time, marking some sort of crisis somewhere in the world every ten to eleven years. If a crisis cannot be found, Jevons (338) looks for some other dramatic event, such as the increase in the price of wool from thirteen shillings to twenty shillings from 1739 to 1744. The number of new companies is cited as an instance of a crisis (337), and changes in the price of tin are cited for another (339). Due to the large variety of events (inconsistently applied) that he would consider a crisis, one gets the impression that Jevons would have found evidence for a cycle theory based on any period.[9] Jevons (335) admits that he is resuscitating a theory he could not prove three years earlier: “Subsequent inquiry convinced me that my figures would not support the conclusion I derived from them, and I withdrew the paper [presented three years earlier] from publication. I have since made several attempts to discover a regular periodicity in the price of corn in Europe, but without success.” In another 1878 article, Jevons (1878a, 34) comes to terms with the fact that a more recently updated estimate of the solar period is 10.45 years, not the 11.1-year period he had used before. But instead of being flustered by this update, Jevons (34) says that the new period fits his theory even better.[10]

The Role of Market Psychology in Jevons’s Sunspot Theory

Peart (1991, 244) notes the role of moods in Jevons’s sunspot articles: “But there is more endogeneity than Jevons has been given credit for, and the transmission mechanism (from the sunspot to the economic cycle), is more sophisticated than has generally been recognized. Like John Mills, Jevons emphasizes the role of expectations or moods in the cycle, moods which he believed to be unstable—‘ever ready to break into a ripple.’” While the large majority of the volume of Jevons’s sunspot theory articles is spent on aligning the sunspot cycle with the business cycle, Jevons also relates agricultural output, news of agricultural output (separately), credit, profitability, moods and expectations, and even capital theory in his explanation of how business cycles play out.[11]

In Jevons’s first work that mentions sunspots, “The Solar Period and the Price of Corn,” published in 1875 (Jevons 1884, 194–205), he attempts to convince the reader of the correlation between the crises of the past few decades and the timing of the number of sunspots. After this, he acknowledges John Mills: “It is true that Mr. John Mills, in his very excellent papers upon Credit Cycles . . ., has shown that these periodic collapses are really mental in their nature, depending upon variations of despondency, hopefulness, excitement, disappointment and panic. But it seems to me very probable that these moods of the commercial mind, while constituting the principal part of the phenomena, may be controlled by outward events, especially the condition of harvests” (203–4).

Jevons (1884, 204) explains that he is looking for some external factor that influences the moods of an entire population: “Assuming that variations of commercial credit and enterprise are essentially mental in their nature, must there not be external events to excite hopefulness at one time or disappointment and despondency at another? It may be that the commercial classes of the English nation, as at present constituted, form a body, suited by mental and other conditions, to go through a complete oscillation in a period nearly corresponding to that of the sun-spots.”

In his next major work on sunspots, “The Periodicity of Commercial Crises,” published in August 1878, he once again acknowledges John Mills, Jevons (1878b, 340): “Mr. John Mills, who has so ably treated of Credit Cycles, . . . attributes the periodic variation to mental action. A commercial panic he holds is the destruction of belief and hope in the minds of merchants and bankers. But though I quite agree with him so far, I can see no reason why the human mind in its own spontaneous action should select a period of just 10.44 years to vary in.”

Jevons (1878b, 340) posits that sunspots and business cycles are linked because “merchants and bankers are continually influenced in their dealings by accounts of the success of harvests, the comparative abundance or scarcity of goods.” One of the events in Jevons’s series of crises is associated with “stock-jobbing” or day-trading—it is described with terms like “mania,” “gambling,” “fervour,” “epidemical,” “fraud, corruption, and iniquity” (1878a, 337; see also 1878b, 35). In his November 1878 article in Nature, he deals with the updated sunspot period (from 11.1 to 10.45 years), and notes that he had to explain the unsatisfying fit of the data to the 11.1-year period by agreeing with John Mills that commercial moods oscillate unexplainably: “To explain this discrepancy I went so far as to form the rather fanciful hypothesis that the commercial world might be a body so mentally constituted, as Mr. John Mills must hold, as to be capable of vibrating in a period of ten years, so that it would every now and then be thrown into oscillation by physical causes having a period of eleven years” (Jevons 1878a, 34).

Peart (1991) highlights Jevons’s references to expectations and moods in his 1879 article in the Times, in which he held that investors and their moods are always lagging actual economic performance in key international markets, such that achieving the “correct” level of investment is difficult, if not impossible (Jevons 1977, 573–74). Thus, we see in Jevons a similarity to the disequilibrating tendencies of investment spending in Keynes. In the same year, Jevons published “Commercial Crises and Sun-Spots” in Nature. Here we see familiar Keynesian language: “The impulse from abroad [foreign trade with India and China] is like the match which fires the inflammable spirits of the speculative classes. The history of many bubbles shows that there is no proportion between the stimulating cause and the height of folly to which the inflation of credit and prices may be carried. A mania is, in short, a kind of explosion of commercial folly followed by the natural collapse” (Jevons 1884, 243).

Peart (1991, 254, 256) notes that “swings in commercial mood” are a feature in Jevons’s economic analysis “throughout his career,” and that Jevons “found many causes of altering moods” but singled out the effects of agricultural output due to his unassailable hunch that it is determined by a sunspot cycle. Peart (262) concludes that the nugget of truth in Jevons’s discredited sunspot theory is his explanation of the relationship between agricultural fluctuations, expectations, and the multiplicative effect of these expectations and speculation after a significant agricultural fluctuation.

Keynes Salvages the Psychological Components

In The General Theory (1964) and in his biography of Jevons, we see Keynes grapple with Jevons’s theory of the trade cycle. Keynes discarded the sunspot and agricultural causes but salvaged the psychological components. His trade cycle theory is notably bereft of any real cause—cycles are started and sustained by the “disobedient psychology of the business world” (Keynes 1964, 317).

Keynes’s “Notes on the Trade Cycle”

Keynes (1964, 313) begins his chapter on business cycles in The General Theory by noting that the primary cause of widespread economic fluctuations is swings in marginal efficiency of capital, or the expected return on capital purchases. These expectations are on shaky psychological ground, however: “Being based on shifting and unreliable evidence, they are subject to sudden and violent changes” (315). Keynes (314) says that any change in the amount of investment that is not matched by a corresponding change in consumption will result in a change in employment, and these changes are “subject to highly complex influences,” including agricultural fluctuations, which he discusses at the end of the chapter.

Keynes (1964, 315), like Mills, begins his description of the phases of the cycle with the “later stages of the boom and the onset of the ‘crisis.’” The end of the boom is marked by optimistic expectations about the return on capital, in which investors do not pay attention to the underlying fundamentals of what they are buying (314–15). This results in a “catastrophic” fall when “disillusion falls upon [such] an over-optimistic and over-bought market” (316). The crisis is almost unfixable, especially by a central bank, because “it is not so easy to revive the marginal efficiency of capital, determined, as it is, by the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world” (317). Again like Mills, Keynes (317) suggests that the mere passage of time is required for recovery to take place, though he does argue for heavy government intervention in both the boom and bust phases to correct the perennially incorrect foresight of those engaged in investment spending, who are always either overoptimistic or overpessimistic. One exacerbating factor may be the population’s “stock-mindedness.” If the population restricts consumption due to declining stock prices, then the economy suffers problems from both the “propensity to consume” and the “marginal efficiency of capital”—both consumption and investment spending levels are “incorrect.” Keynes (320) explicitly rejects laissez-faire and “individualistic capitalism” because consumers and investors cannot be trusted to spontaneously adopt the correct psychology for recovery to take place: “In conditions of laissez-faire the avoidance of wide fluctuations in employment may, therefore, prove impossible without a far-reaching change in the psychology of investment markets such as there is no reason to expect. I conclude that the duty of ordering the current volume of investment cannot safely be left in private hands.”

David Laidler (1999, 271) notes that while Keynes cites neither Pigou nor Frederick Lavington, the trade cycle theory in this chapter closely resembles their work—Keynes “even adopts their vocabulary.” And despite the fact that “the General Theory is not primarily about the cycle” (Laidler, 248), there is enough substance in this chapter for Laidler to conclude that it aligns with Pigou, Lavington, and the “mainstream of the Cambridge tradition” (Laidler, 271) and that it may be categorized as a psychological theory of the trade cycle (271n26).[12] Pigou (1967, 208) cites Jevons in Industrial Fluctuations, published in 1927: “Thus prosperity, whether due to a good harvest, to an invention, or to anything else, is liable to promote an error of optimism; and adversity an error of pessimism. This point was brought out very clearly by Jevons when he wrote: ‘Periodic collapses are really mental in their nature, depending upon variations of despondency, hopefulness, excitement, disappointment and panic.’” And Lavington (1922, 54) refers to “solar changes” that may influence harvests and therefore the optimism or pessimism of businessmen. Thus, Jevons’s cycle theory influenced Keynes both indirectly, via other Cambridge economists;[13] and directly, as Keynes (1964, 329–32) cites Jevons near the end of his trade cycle chapter in The General Theory.

Keynes (1964, 329–32) discusses Jevons’s sunspot theory without using the term “sunspots,” though we have already seen many similarities between Jevons’s and Keynes’s cycle theories even before Keynes cites Jevons. Keynes admits that Jevons’s theory (or at least Keynes’s interpretation of Jevons’s theory) is wholly compatible with Keynes’s cycle theory.[14] There are only two slight differences in application, according to Keynes (331): (1) agricultural output is a much smaller part of modern economies, so the effects of good and bad harvests do not significantly change total consumption or investment spending; and (2) globalization has diversified food sources all over the world, including both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, so any bad harvests in one region are averaged out. Keynes (331) applies Jevons’s emphasis on changes in agricultural output to a modern economy’s “changes in the stocks of raw materials, both agricultural and mineral” due to the effect both have on “the rate of current investment,” which, as we have seen, is also determined by spontaneous gyrations in moods. Keynes, however, explicitly discusses only the agricultural aspects of Jevons’s theory—the influence of market psychology is implied. In his 1936 biography of Jevons, though, Keynes provides a more thorough discussion of the market psychology catalysts in Jevons’s cycle theory.

Keynes’s Biography of Jevons

Keynes read his biography of Jevons to the Royal Statistical Society in April 1936, just a few months after he finished writing The General Theory. Keynes’s (1936, 524) first statement regarding the content of Jevons’s contributions on economic fluctuations (his first remarks praise Jevons’s pathbreaking methodology) is that it had to do with “seasonal fluctuations in the minds of business men.” Next, Keynes praises Jevons’s pioneering work in creating and using indexing methods to estimate the fall in the value of gold due to the increased supply of gold in the mid-nineteenth century. Keynes (525) quotes Jevons directly on the economic consequences of the fall in the value of gold, highlighting the psychological impact on economic activity: “It excites the active and skilful classes of the community to new exertions.” Keynes (526) cannot avoid mentioning Jevons’s widely ridiculed sunspot theory, but does so by pointing the reader to “the underlying causes of the cycle”: “His observations on the underlying causes of the trade cycle, though merely obiter dicta, strike deeper, in my judgement, than those which he popularized later.”

Thus, Keynes saw through the sunspots in Jevons’s work and found something valuable: changes in commercial moods. Later in the biography, Keynes (1936, 529) highlights the commercial mood elements of Jevons’s works (“He discovered the link in the spirit of optimism produced by good crops”) and includes a full quote from Jevons’s “The Solar Period and the Price of Corn” that acknowledges Mills. Keynes concludes his remarks on Jevons’s sunspot theory with the suggestion that Jevons’s whole project could have been saved if he had only kept it in terms of the fluctuations in investment compared to consumption, which is how Keynes interpreted and summarized the theory in The General Theory.

Conclusion

We have traced one precursor to John Maynard Keynes’s emphasis on market psychology back through William Stanley Jevons’s sunspot theory to John Mills’s credit cycle theory. While Mills’s work anticipated many features of what would later become Austrian business cycle theory, he placed a heavy emphasis on the mental moods of market participants in each phase of the business cycle. Jevons’s theory was and is widely ridiculed, but it should not be overlooked that he continued and developed John Mills’s emphasis on fluctuations in market psychology. Keynes, for his part, did not overlook this feature in Jevons’s sunspot articles. In The General Theory, Keynes shows how his interpretation of Jevons’s sunspot theory is perfectly compatible with his own trade cycle theory. And in his biographical essay on Jevons, Keynes highlights the psychological aspects of Jevons’s theory. Jevons’s influence on Keynes and other Cambridge economists may explain Keynes’s overwhelming use of market psychology in his macroeconomic theory in general and in his trade cycle theory in particular—both of which are monumentally influential in government policy decisions even today.

While Mills may be seen as a precursor to Keynes via Jevons, it is clear that Jevons jettisoned the proto-Austrian aspects of Mills’s cycle theory, and the remainder wound up in Keynes’s cycle theory. By discarding the influence of artificial credit on generating business cycles, malinvestment, and the corresponding patterns of commercial moods, Jevons left the causes of these economic and psychological phenomena unexplained. It comes as no surprise, then, that Keynes distrusted the ability of unhampered markets to operate sustainably. If optimism and pessimism are not anchored to anything in economic reality, then they will steer consumption and investment off course and generate endless business cycles that can be corrected only by state intervention. A full and close reading of Mills, however, shows that the Austrian insight that business cycles are caused by artificial credit expansion is the more complete explanation.

Jevons developed his sunspot theory over several articles spanning the years 1875–82: “The Solar Period and the Price of Corn” (1875), “The Periodicity of Commercial Crises and Its Physical Explanation” (1878), “Commercial Crises and Sunspots” (1878), “The Solar Influence on Commerce” (1879), and “The Solar Commercial Cycle” (1882). While Jevons’s original articles are referenced in this present article, I cite and rely on Sandra Peart’s (1991) excellent work in compiling and summarizing Jevons’s theory in “Sun Spots and Expectations: W. S. Jevons and the Theory of Economic Fluctuations.”

Mills may also have been influenced by Lord Overstone’s characterization of cycles. Consider his vivid labels for each stage of the cycle: “The history of what we are in the habit of calling the ‘state of trade’ is an instructive lesson. We find it subject to various conditions which are periodically returning; it revolves apparently in an established cycle. First we find it in a state of quiescence, —next improvement, —growing confidence, —prosperity, —excitement, —overtrading, —convulsion, —pressure, —stagnation, —distress, —ending again in quiescence” (Overstone 1837, 44). Lord Overstone was also a part of the currency school, which cautioned against fiduciary media; this likewise aligns with John Mills’s “On Credit Cycles,” discussed below.

Peart’s interpretation agrees with Rothbard’s (2006, 251) reading of Mill: “Instead of seeing the new phenomenon of business cycles as created by monetary disturbances, he saw them as caused by waves of ‘speculation,’ presumably generated by over-optimism. Money and banks were purely passive respondents to fluctuations in the economy.”

Mills’s (1867, 19) language in describing the panic is very colorful and dramatic: “As a first result of that destruction, a mass of paper documents, the outward expressions of those beliefs from which they derived their circulating force, becomes a mere dead residuum, leaving a void which can only be filled by other agents possessing that vital grasp on belief which they have lost. And the void must be filled.”

According to Rothbard (2000, 6), “We may, therefore, expect specific business fluctuations all the time. There is no need for any special ‘cycle theory’ to account for them. They are simply the results of changes in economic data and are fully explained by economic theory. . . . Shifts in data will cause increases in activity in one field, declines in another. There is nothing here to account for a general business depression—a phenomenon of the true ‘business cycle.’”

Mills continues by discussing the impact of credit on “the mental mood of traders” (27), which indicates that his use of the term “Credit” in the preceding text meant bank lending, not “mental moods.”

However, in Mills’s (1866, 9–10) The Bank Charter Act and the Late Panic, he argues against allowing banks to mitigate losses from bad loans by decreasing reserves that back banknotes.

I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer for this point.

“I have, therefore, spent much labour during the past summer in a most tedious and discouraging search among the pamphlets, magazines, and newspapers of the period [South Sea Bubble of 1720], with a view to discover other decennial crises. I am free to confess that in this search I have been thoroughly biased in favour of a theory, and that the evidence which I have so far found would have no weight if standing by itself” (Jevons 1878a, 35).

Lionel Robbins (1982, 322) notes, “The cycles did not always fit; two of the biggest crises of the century fell outside the series. The sunspot cycle was revised; and the list of crises was found to be so elastic that it was possible to revise it too.”

One of Jevons’s more prescient observations (also noted by Keynes 1936, Robbins 1972, and Hayek 2008) in some remarks on the trade cycle published after his death points to the proportions of capital invested in various stages of production: “The remote cause of these commercial tides . . . seems to lie in the varying proportion which the capital devoted to permanent and remote investment bears to that which is but temporarily invested to reproduce itself” (Jevons 1884, 27–28). Indeed, Hayek (2008, 228–229n41) favors a suggestion that what are commonly known as “Hayekian triangles” today be called “Jevonian Investment figures.” Keynes (1936, 272) includes the same quote in his biography of Jevons, but does not comment on this point—a point that is critically important for Austrian capital theory and business cycle theory.

I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer for bringing this to my attention.

Alfred Marshall, another important influence on Keynes, was primarily influenced by Lord Overstone’s (1840) cycle theory. Eshag (1963, 95n101) notes that “in a passage read and carefully marked by Marshall in his personal copy of the book [Overstone 1840], he attributes the ‘original exciting causes’ of the ‘variations in the state of trade,’ to ‘the buoyant and sanguine character of human mind; miscalculations as to the relative extent of supply and demand; fluctuations of the seasons; changes of the taste and fashion’ and other ‘casualties acting upon these sympathies by which masses of men are often urged into a state of excitement and depression.’” John Mills may have been influenced by Lord Overstone as well (see footnote 2).

Writing in 1959, Henry Hazlitt (2007, 333–36) takes Keynes to task for his endorsement of Jevons’s cycle theory. Hazlitt (334–35) says that the burden of proof was on Keynes to show that there is a statistical correlation between the size of harvests and the macroeconomic data associated with the business cycle. Hazlitt does not comment on the psychological aspects of Jevons’s theory.