Ludwig von Mises left behind a large body of economic work that is still cited and received today; however, his scientific positions have been increasingly questioned since the late 1920s due to the success of Keynesian doctrine. Also, the establishment of neoclassical theory and its methodology as the mainstream in economics led to less reception of Mises’s work. His student Friedrich August von Hayek gained greater popularity and recognition in the field, which was reflected in his being awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. Ludwig von Mises never held a classical chair in economics; at New York University he was a visiting professor and taught economics to MBA students. These facts raise the question of what position and standing Ludwig von Mises held in economics and the social sciences then and holds today. Was it an isolated, outsider position or a unique, exceptional position?

There are many assessments in the literature that Ludwig von Mises held an isolated position in the field of economics and in academia. The most famous assessment may have become that of Mises’s student F. A. Hayek (2009, xiii): “Although without a doubt one of the most important economists of his generation, in a certain sense Ludwig von Mises remained an outsider in the academic world until the end of his unusually long scholarly career—certainly within the German-speaking world—but also during the last third of his life, when in the United States he raised a larger circle of students.” In the preface to Mises’s biography, Hayek paints a picture of an increasingly isolated scientist who worked in seclusion from economists as well as from his Viennese environment and public life. Hayek also argues that Mises’s social philosophy was little known and little understood and that this only improved in 1940 with the publication of Nationalökonomie: Theorie des Handelns und Wirtschaftens (National economy: Theory of action and economics, later expanded into the English-language book Human Action: A Treatise on Economics). In his biography, Mises (2009, 88) even ascribes to himself an outsider position in Germany: “As an Austrian, as a Privatdozent, and as a ‘theorist,’ I remained an outsider to the Verein [Verein für Socialpolitik, a German association of economists]. I was treated with the utmost courtesy, but I was seen as a stranger.” Gane (2014) describes Mises as an outsider in neoliberal circles, belonging to neither the Chicago school nor the Virginia school, and even within the Mont Pelerin Society he had different positions from many of his colleagues, especially Milton Friedman (see Gane 2014, 6): “Over time Mises became an increasingly isolated figure, existing only at the edge of the neoliberal movement.” Mises also took isolated positions in other disciplines. Douma (2018, 360) describes how Mises’s conception of historiography in his work Theory and History met with incomprehension and low acceptance among American historians: “The primary reason why the book never caught on was that Mises was an outsider in contemporary Anglo-American debates in historiography.” “It was too philosophical, too foreign, too liberal, and too broad” (362). Douma acknowledges Mises’s methodological contributions to the study of history: “It is certainly unfortunate that this book was not better understood or widely read and applied. Mises’s contribution to the philosophy of history is unique” (370). Callahan (2005, 231) ascribes outsider status to Mises’s view of the social sciences and human action, leading the mainstream to neglect Mises’s different methodological view.

Hülsmann (2009, viii), on the other hand, comes to a very different assessment of Ludwig von Mises’s position until 1940: “He not only knew the intellectuals of his day, he had almost daily interaction with the political leaders of his country, with the higher echelons of the civil service, and with the executives of Austrian firms and business corporations.”

On the basis of a content-analytical evaluation of Mises’s most important publications, this article attempts to trace his central scientific positions and to draw conclusions about the research profile and position Mises held in economics. This will provide an answer to the question of whether it is justified to consider Mises’s position as isolated or whether it should rather be interpreted as a unique research profile.

In the following, a distinction is made between the scientific profile of a researcher and his or her position in the scientific community. The scientific profile of a researcher can be characterized by the breadth of the research areas in which he or she works. Likewise, the scientific profile is characterized by the depth and duration of the researcher’s engagement with his or her subject areas as well as by the interdisciplinary or disciplinary orientation and the methodological standpoint of a researcher. The scientific profile of a researcher can be assessed relative to the scientific profiles of other researchers.

A researcher’s standing in the scientific community and in practice is determined by whether and to what extent a researcher’s work is cited by other researchers, what influence the research has on scientific discussion or practical economic policy, and whether the researcher has supporters, students, or admirers—that is, a scientific and personal network. Accordingly, a researcher can occupy an isolated or integrated position in his or her research community and environment. A researcher is isolated if his work is not read and cited by experts, if his work has no influence on the economic theory debate or practical economic policy, and if he has no supporters, students, or admirers.

These two criteria can be combined and evaluated together: A researcher may have a unique scientific profile and yet be isolated in the scientific community. Conversely, a researcher can have a general scientific profile that is very similar to that of many other researchers and still be integrated into the scientific community.

The structure of the article is as follows: Part 1 presents Mises’s central works from 1902 to 1933 in chronological order. Based on this, part 2 shows to what extent Mises had a unique position in economics due to his unique research profile. For this purpose, thematic foci (section 2.1), the substantive positions and research results (section 2.2), as well as methodological positions (section 2.3) in Mises’s main publications are analyzed. The relationship of Mises to the Austrian school (section 2.4), his proximity to business practice and business administration (section 2.5), and his emphasized interdisciplinary approach to research (section 2.6) are also analyzed to complete the complex research profile (section 2.7). In part 3, the central arguments for Mises’s outsider position in economics are first presented. Then, the citations of Mises’s works then and today and his impact on economics and economic policy are described. Finally, an answer to the question of whether Mises’s position was that of an outsider in economics will be given.

1. The Main Publications of Ludwig von Mises

In the following section, Mises’s most important publications are presented individually.

Under the guidance of his teacher Carl Grünberg, Mises wrote his PhD dissertation at the University of Vienna on the development of relations between landlords and peasants in Galicia and published it in 1902 (see Polleit 2018, 30). His dissertation was entitled Die Entwicklung des gutsherrlich-bäuerlichen Verhältnisses in Galizien (1772–1848) (The development of the landlord-peasant relationship in Galicia [1772–1848]) (Mises 1902). Mises wrote the thesis in one year. His PhD dissertation traces the institutional and economic changes that ultimately led to the abolition of peasant serfdom in Galicia, a province of the then Austrian empire.

Mises’s first publications on exchange rate policy and monetary and banking issues took the form of journal articles in 1907–9. These smaller publications are neglected in this article.

In his 1912 habilitation thesis, entitled Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel (translated as The Theory of Money and Credit), Mises showed that the subjective theory of value and the law of diminishing marginal utility apply to money as to any other commodity. Building on this, Mises was able to show that money can be historically traced back in a finite regress to the original anchoring of value in a real asset (e.g., gold) (so-called regression theorem). Money is thus not a deliberately planned creation of the state but has evolved evolutionarily and spontaneously between market partners in barter from a real good (e.g., gold, silver) with certain nonmonetary properties valued by users (see Polleit 2015, 11, 130). Mises was an opponent of the state monopoly on money, fearing political influence on money supply and interest rates. He was a proponent of the provision of money by private banks, which compete with each other as money issuers. Competition among banks in the provision of credit would reduce the extent of credit expansion (see Kirzner 2001, 147). In his habilitation thesis , Mises (1912) developed initial ideas on a theory of the monetary business cycle of the Austrian school. He thus demonstrated that money is not a neutral veil—the view of quantity theory—but that a change in the money supply affects real economic activity and generates redistributive effects.

Mises takes his first scholarly look at socialism in his book Nation, Staat und Wirtschaft (translated as Nation, State, and Economy) as early as 1919. In this book, Mises analyzes the increasingly state-planned war economy in Germany and Austria-Hungary during World War I and comes to a negative assessment of war socialism (see Polleit 2018, 73–74).

Mises published an essay in 1920 entitled “The Economic Account in the Socialist Commonwealth.” This essay and the argumentation developed in it became the basis of his later critique of all forms of socialism, including interventionism and bureaucracy (see Kirzner 2001, 44). In the 1920 paper, Mises logically demonstrated that socialism could not work, because of difficulties in its realization. He saw the core problem in the fact that the nationalized means of production did not create a market for capital goods and other factors of production (labor, land) with market prices (see Leipold 2010, 80). However, since important price and cost information is thus missing, rational economic accounting, in the sense of planning, calculation, and control of investment projects, is not possible (the so-called impossibility theorem of rational economic accounting in the socialist polity). Mises (1920, 104) comes to the overall result: “Socialism is abolition of the rationality of the economy.” He thus presents in this essay “the scientific refutation of socialism. It is a final scientific justification that reveals that socialism cannot work” (Polleit 2018, 77).

Mises elaborated on the basic ideas of the 1920 article in his book Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen über den Sozialismus (translated as Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis), published in 1922. There, he also addresses more far-reaching problems, such as questions of income distribution and incentives for performance and technical progress or innovation under the conditions of a socialist economic system (see Leipold 2010, 81). Mises (1922, 496, 488) arrives at the (damning) overall verdict: socialism does not mean “prosperity for all” but “hardship and misery for all.”

After providing argumentative evidence for the logical impracticability of socialism, Mises asked himself why socialism is nevertheless so popular, especially among intellectuals and among workers. He attributes this to self-deceptions of the masses, who “believe that socialism suits their interests” (Pies 2010, 10). However, Mises (see 1922, 423; 1958) also provides a psychological explanation for the rejection of capitalism by intellectuals and artists: Under capitalism, everyone would have opportunities for advancement, but only a few can reach the top positions in society and the economy. Those left behind do not admit their failure and instead develop reservations and resentment against the capitalist economic system.

Mises published a smaller paper on questions of monetary theory in 1923 under the title “Die geldtheoretische Seite des Stabilisierungsproblems” (The monetary theory side of the stabilization problem). Mises (1923, 3) states that monetary stabilization “could not and cannot be achieved.” He warns against financing deficits in the national budget with money creation. To avoid inflationary tendencies and collapse of the currency, he proposes the gold standard of the currency.

In his 1927 work Liberalismus (translated as Liberalism: In the Classical Tradition), Mises attempts to summarize liberal doctrine and to develop and recombine the liberal program so that it can survive the competition with socialism. His starting point of consideration is the question of how to achieve the most efficient use of resources and thus promote the prosperity of all people. For Mises, the means to this end is liberalism. Central to the understanding of liberalism is private ownership of the means of production. On this basis, rational economic activity is possible through calculation with the help of market prices, costs, and returns. It is noteworthy that Mises conceives of a liberal economic order as a means to an end—that is, functionally: a liberal market order is the best (or only suitable) means to achieve the goals of cooperation in society based on the division of labor. Liberalism is thus not preferred because of the values associated with it, such as peace and freedom, but because liberalism is suitable for promoting cooperative value creation in a society and the prosperity of all (see Hielscher 2010, 152–53). For Mises, liberalism is an economic policy program and a sociopolitical program. The core and basic premise of liberalism is private ownership of the means of production (land, capital, machinery, and intermediate goods), on which economic liberalism is founded (see Engel 2010, 115). The central difference between liberalism and socialism is that the former argues for individual ownership of the means of production and the latter for the socialization of the means of production (see Bluhm 2010, 192). Mises’s contribution to liberal thought can be appreciated as follows: “His book Liberalism, published in 1927, is probably the most radical plea for individual freedom to exist in the German-speaking world in the interwar period” (Doehring 2008, 258).

In his 1928 publication Geldwertstabilisierung und Konjunkturpolitik (translated as On the Manipulation of Money and Credit: Three Treatises on Trade-Cycle Theory), Mises (1928, 1, 3, 41–42) fleshes out his monetary policy positions on several points. He argues on the basis of quantity theory and elaborates his monetary theory of the business cycle, denies the possibility of stabilizing the value of money and eliminating business cycle fluctuations, and thus takes positions in his work that are contrary to the thinking in mainstream economics. Thus, he holds that stable money is impossible because in a dynamic world the purchasing power of money necessarily fluctuates and cannot be stabilized by government action. “Consequently, all policies aimed at stabilizing the value of money are doomed to fail. Worse, policies aimed at keeping the value of money stable necessarily lead to disturbances in the market and price structure” (Polleit 2018, 162). Mises (1928, 20–23) negates the measurement of changes in purchasing power because of problems of statistical detectability and aggregability of price changes of individual goods into a price index: “The idea that it is possible to measure changes in the purchasing power of money is scientifically untenable.” He likewise considers a stationary economy without business cycles to be an unattainable ideal, and he states, “Finally, a stationary economy (supposing it could be realized) would certainly not fulfill what one might hope from it” (38). Mises (72) is critical of business cycle control through business cycle monitoring and business cycle policy.

In his 1929 book Kritik des Interventionismus: Untersuchungen zur Wirtschaftspolitik und Wirtschaftsideologie der Gegenwart (translated as A Critique of Interventionism), Mises (2011, 22) treats state regulation of private business activity and private property as a third way between the market (capitalism) and the state economy (socialism). Here, private ownership of the means of production is not abolished, but it is restricted by state intervention. Interventionist economic policy realizes an “economy constrained by state and other interventions” (80). He points to evasion and avoidance attempts by regulated firms, which lead to further interventions as well as a tightening and greater detail of government interventions, setting in motion an intervention spiral (41). The dysfunctional effects of interventionism ultimately lead to a great crisis of the economy: “The great crisis from which the world economy has suffered since the end of the war [the First World War] is called by the etatists and socialists the crisis of capitalism. In truth, however, it is the crisis of interventionism” (47). Mises passes a harsh judgment on interventionism: “Interventionism itself, as an economic system, is contrary to purpose and meaning, and once this is recognized, the only choice is between the elimination of all intervention or its shaping into a system in which the government directs all the steps of entrepreneurs, in which the decision as to what and how to produce and under what conditions and to whom to deliver the products belongs to the state, in short, into a system of socialism in which what remains of the private property in the means of production is at most the name” (93). The consequence of this is “either capitalism or socialism; there is no middle thing” (36).

To sum up: The peak of Mises’s scholarly output was in the 1920s, marked by his writings on socialism (Mises 1920, 1922), liberalism (Mises 1927) and state interventionism (Mises 1929). He thus published his most important writings between the ages of thirty-nine and forty-nine. His most outstanding scientific research papers, which established his reputation as a scholar in the professional community, are the habilitation thesis on the theory of money (Mises 1912) and his works on socialism. His work on liberalism had the strongest impact on politics and society and the strongest resonance in business practice.

If one looks at Mises’s topics and lines of argumentation in his most important works, it is only logical that he also took very particular, sometimes extreme, positions on fundamental methodological issues. The first summarizing presentation of his methodological and epistemological positions is made in 1933 in his book Grundprobleme der Nationalökonomie: Untersuchungen über Verfahren, Aufgaben und Inhalt der Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftslehre (translated as Epistemological Problems of Economics). This is a summary of previously published journal articles. Only one contribution is newly written (Mises 1933, chap. 12). Mises presented in this book his own methodological approach, which he called praxeology, and demarcated his methodological understanding of economics and related sciences. In it, he outlines his understanding of the general science of human action (praxeology) and treats basic methodological problems of economics.

Mises addresses the various directions of philosophy of science, such as utilitarianism, rationalism, historicism, and empiricism; he argues in favor of utilitarianism and rationalism and against historicism and empiricism. In Mises’s (1933, 28) view, theories cannot be refuted or confirmed on the basis of empirical experience but only by better theories: “The complex character of historical experience entails that the inadequacy of an incorrect theory does not impose itself more compellingly when it is held up against the facts than when it is measured against the correct theory.” He thus rejects the falsifiability of theories by experience and empirical facts; however, his approach is not completely free of empiricism and experience: “Only through experience, however, can it be determined whether the categorical conditions of action presupposed by the theory actually exist in the concrete case” (41).

Mises builds his praxeological approach axiomatically by breaking down the proposition “Man acts” further and further. “Our science is concerned with the forms and figures of action under the various categories of conditions of this action” (16). “The starting point of our thought is not the economy, but economic activity, i.e., action, or, as one pleonastically tends to say, rational action” (22). He pleads for methodological individualism: “In science, we start from the action of the individual, because we are only able to recognize this directly. The idea of a society that could act or become visible outside the actions of individuals is absurd. In the action of the individual everything social must be somehow recognizable. . . . Every social entity acts in a certain directed action of individuals” (41). Mises has elaborated a concept of action: “The most general condition of action is a state of dissatisfaction on the one hand and the possibility of a remedy or mitigation of this dissatisfaction through action on the other” (23). “The motives of action and the ends toward which it tends are data for the doctrine of action, their shaping influences the course of action in the individual case, without affecting the essence of action thereby” (33). He sees a priori true law-like regularities governing all human behavior, the uncovering of which is a task of praxeology. He enumerates as law-like regularities the following: “The economic principle, the fundamental laws of the formation of exchange relations, the law of profit, the law of population, and all other propositions are always and everywhere valid where the conditions they presuppose are given” (82–83).

2. Ludwig von Mises’s Position in Economic Research—a Unique Research Profile?

In this section, Mises’s research topics, his positions and research results, his methodological positions, and his interdisciplinary approach are analyzed over a long period of thirty years.

2.1. The High Relevance and Breadth of Mises’s Research Topics from 1902 to 1933

“From the very beginning of his scholarly work, Mises grappled with the important, the major sociotheoretical and sociopolitical questions of his time” (Polleit 2018, 47). F. A. Hayek (1977, xvi) states, “The problems with which he concerned himself were mostly problems for which he considered the prevailing opinion false.” Mises’s research interest covers seven scientific main topics: monetary theory and monetary business cycle (Mises 1912, 1923, 1928), critique of socialism (Mises 1920, 1923), reformulation of liberalism (Mises 1927), critique of interventionism (Mises 1929), social theory and other disciplines (Mises 1923, 1929, 1933), and methodological problems of economics and philosophy of science (Mises 1933). Mises made important contributions to monetary theory and policy and to the monetary explanation of business cycles at the beginning of his academic career. Central themes in his subsequent scholarly work are the debate on socialism versus liberalism and capitalism and the question of a third way between market and state—for example, state interventionism.

The topics Mises worked on were of high relevance for academic research, economic policy, and business policy. And the scope and breadth of his research topics are impressive, the topics very heterogenous and intellectually demanding. From the economists of his time, only Schumpeter and Hayek have a comparable breadth and width in their fields of research and a research profile comparable to Mises’s.

2.2. Mises’s Extreme and Controversial Positions in His Research Fields

Mises never makes compromises in his research results and intellectual positions; therefore, he is at odds with nearly all positions of economic research (in the beginning with the historical school of economics and Marxism, later with neoclassical economics and Keynesianism). Mises (1912) insists that money is the result of evolutionary processes and not an institution designed by the state. Also, his interpretation of the business cycle as a phenomenon induced by monetary policy of the state and by banks is a contradiction to neoclassical economics and refutes Keynes’s central positions. Neoclassical explanations of the business cycle focus on capital accumulation, change of labor supply, and change of exogeneous factors like technological disruption and change of preferences (King, Plosser, and Rebelo 1988). Keynes’s (1936) explanation of the business cycle focuses on demand deficits and the role of state policy in overcoming an economic recession. Mises’s (1923) statement that stable money is an illusion, that the measurement of inflation by statistical indicators is not possible, and that the state should avoid all policies aimed at stabilizing the value of money is a verdict against all forms of economic policy and bureaucratic action. Mises (1920) and Mises (1923) are a scientific, intellectual, and logical assault on Marxism and its defenders. His defense of liberalism in Mises (1927) is a provocation for the public opinion (zeitgeist) in many Western countries in the 1930s. Mises’s (1929) condemnation of state interventionism and his refutation of a third way between market (liberalism) and state (socialism) is a disillusion for state planning of the economy, bureaucrats, and a demasking of special interest groups. Mises’s (1933) methodological positions are incompatible with Popper’s critical rationalism. His own methodological approach (praxeology) is a negation of and resistance against most methodological trends (formal modeling, graphical representation, empirical research) in economics since World War I. Mises held extreme substantive positions and was not afraid to deviate from the standard views in science and economic policy of his time. He emphatically defended his own positions. After his PhD dissertation writing, at the latest, Mises represented decidedly liberal and free-market positions. He was a pronounced opponent of state economic policy, rejected state monetary policy, and vehemently opposed all socialist, planned economy, and welfare state tendencies in science and economic policy. One can judge his positioning as follows: Mises was outside the economic mainstream and he was swimming against the tide of economic thinking and state policy of his time.

2.3. Mises’s Research Methodology from 1902 to 1933

A main field of Mises’s research were problems of methodology and epistemology—in particular, Mises’s own approach, praxeology as the science of human action (see Pies 2010, 6). Methodologically, Mises followed his own particular paths.

The PhD dissertation (Mises 1902) has no implications for Mises’s further scientific work in methodological terms. Carl Grünberg, his PhD adviser, was a follower of the historical school, and this was reflected in the treatment of the topic and methodology of his student. In terms of methodology, the work adhered to the historical school of economics and was based on extensive file and archival research. In his later research, Mises distanced himself from the methodology of the historical school he had applied in his dissertation. After turning away from the methodology of the historical school, Mises joined the methodological position of the Austrian school of economics.

For the understanding and development of Mises’s methodological position, the habilitation thesis (Mises 1912) was more important than his PhD dissertation. Mises pursues a science of argumentation, weighs arguments, deals with earlier doctrines and theories, distinguishes himself from them, and develops independent approaches and positions—for example, the explanation of the origin of money and the business cycle. Mises (1912) refrains from empirical survey, mathematical representation, and graphical forms of representation to illustrate complex issues; instead, the arguments are logically weighed against each other and theoretical precursors are referred to, with whose positions he deals in detail. Mises remained true to this scientific style of working until the end of his life.

In a summarized form, Mises presents his own central methodological basic positions in Epistemological Problems of Economics (1933). He rejects positivism, the historical school of economics, and Popper’s critical rationalism, especially their empirical orientation, as useless for the social and economic sciences. In this book, Mises’s interdisciplinary approach to research becomes clear. Mises (1933, vii) sees “sociology and economics as a generally valid science of human action.” He conceives his own methodological approach of praxeology as a system of a priori propositions with a logical character. The aim of the science of human action is “to obtain generally valid laws of human behavior” (64). Economics “is in all its parts not empirical but a priori science; like logic and mathematics, it does not derive from experience, it precedes it. It is, as it were, the logic of action and act.” (12). The praxeological approach is problem-oriented and logical-deductive but free of empirical verification and graphical and mathematical representation. His praxeological concept was hardly taken up by the professional community, but some economists expressed doubts and stated limitations—certainly not in such a radical way as Mises did—concerning the applicability of empirical studies in economics (e.g., Robbins 1932, 104–9). Mises’s strict and harsh refutation of empirical studies and mathematics in economics ultimately led to his position as a methodological nonconformist who clearly stated what he rejected (formal representation, graphical representation, empiricism). The praxeological approach he had advocated since 1933 was not broadly accepted outside the circle of his students and scholars. While his early scientific work is very impressive from a thematic point of view, Mises did not achieve comparable recognition in the scientific community for his treatment of methodological issues.

2.4. Mises and the Austrian School of Economics

After his PhD dissertation, Mises turned to the subjectivist school of Austrian economics, which he adopted only in part and in single theoretical modules and concepts. Mises is considered to belong to the Austrian school of economics. This may have been due to the fact that he studied, earned his doctorate, and habilitated in Vienna and was scientifically influenced by the writings of Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. If one looks at his own writings, however, one is struck by how little he cites authors of the Austrian school and that he often holds deviating and opposing opinions, especially on Schumpeter’s positions (see Mises 1940, 244, where he rejects the distinction between static and dynamic economic theory that Schumpeter advocates). Mises’s relationship with Schumpeter is described by Hayek (1977, xvii, xviii) as nerve-racking and tense. Mises’s (2009, 28) biography also reveals his negative assessment of Friedrich von Wieser, whom he, like Schumpeter, did not consider a member of the Austrian school. Mises refers in his publications to the writings of Carl Menger and the subjectivist school of economics, but his remarks in this regard remain rather brief and superficial; in his writings he never presents the central positions of the Austrian school comprehensively and in detail. He differs from the earlier representatives of the Austrian school in his orientation toward questions of economic policy and practice and in his profound understanding of how government bureaucracies and private firms function internally.

2.5. Mises’s Knowledge of Business Administration and Managerial Practice

Mises is not a typical representative of the Austrian school of economics. He exhibits a closeness in content to business practice on the one hand and to business administration on the other, which was very remarkable for a theoretically working economist. He had numerous points of contact with business practice and business administration.

If one reads Mises’s writings, such as Socialism (1922) or Bureaucracy (1944), one can see that he understands how businesses and government agencies functioned internally and how important economic accounting (cost accounting, calculation, balancing, bookkeeping) is for determining the success of businesses. He has a profound understanding of how businesses, bureaucracies, and political parties functioned internally, what their goals were, how work was organized, how success was determined. He sees the profit target and the systems of cost accounting, calculation, and planning installed in private enterprise as rational instruments that make economic activity in enterprises possible in the first place. He also emphasizes the great differences from the hardly possible determination and evaluation of success in public enterprises and administrations. Mises is well aware of the fundamental differences between commercial enterprises, which are managed according to profit goals, and public administrations, which are managed according to political goals. If one looks at his early publications, it is evident in some places and passages that Mises has a remarkable overview knowledge of business management issues and instruments and knows or is able to recognize interrelationships relevant to business management. This distinguishes him from many other representatives of the Austrian school of economics.

Throughout his professional career, which was anything but a straight path toward a professorship in economics, Mises had the opportunity to come into contact with business practitioners and with thoughts of business administration at several professional stations. After his habilitation (1912), Mises (1978, 45) worked full-time at the Chamber of Commerce, Trade, and Industry in Vienna. In a de facto position as chief economist, he was concerned with economic policy issues of financial, monetary, economic, and fiscal policy. Mises (1978, 48–50) headed the settlement office for the settlement of Austria-Hungary’s prewar debts, so he was able to gain practical experience in managing government agencies. On behalf of the chamber of commerce, Mises (1978, 48) visited industrial centers in Austria to elicit the situation of industry with regard to economic policy issues of the time. It can therefore be assumed that he had contact with business representatives and politicians as part of this activity for the chamber of commerce. In his memoirs, Mises (1978, 46) reports that some major banks wanted to give him a place on the board of directors because of his reputation as an expert on money and banking issues; he turned down all such offers. After emigration to the United States in 1940, he was offered a position as visiting professor of economics at New York University’s graduate school of business. There he worked in the MBA program as a lecturer and was active in the education of students of management (see Kirzner 2001, 18).

Mises—in contrast to Menger, Hayek, and many economists—also sought scientific exchange with Eugen Schmalenbach, the leading business economist of his time in Germany. Schmalenbach argues that the reduced adaptability of firms as a result of rising fixed cost intensity leads to an increasingly state-bound economy (Schmalenbach 1928). Mises’s critique took its cue from Schmalenbach’s central argument. Mises’s 1929 book Critique of Interventionism deals with Mises’s (2011, 20) criticism of Schmalenbach’s position. In this controversial discussion with Schmalenbach, Mises’s interdisciplinary approach and his profound understanding of how a private enterprise operates become obvious. For Mises, this occupation with production and cost structures in private business firms was a new topic.

Mises (2011, 86–87) first summarizes Schmalenbach’s central arguments in Critique of Interventionism, stating that Schmalenbach’s argument for the inevitability of the transition to a “tied economy” is that the share of fixed costs and the capital intensity in companies are increasing more and more, while variable costs are decreasing in relative terms. Due to the changed cost structure, private companies lose flexibility and adaptability, which, according to Schmalenbach, must lead to the end of the free economy. Mises (2011, 88 ff.), however, doubts Schmalenbach’s thesis that due to the increased fixed costs, companies are less able to adapt to changed demands of the demanders and substantiates these doubts by means of practical and logical considerations that could also have come from a business economist.

2.6. Mises as Social Scientist and Interdisciplinary Researcher

The book Socialism (1922) contains important statements about Mises’s scientific methodology. Mises (1922, 7–9) states at the beginning of his book that he conducts a combination of economic and sociological analysis and makes this the precondition of a cultural-philosophical-psychological analysis. In implementing his analysis later in the book, he takes an eclectic approach; economic passages are flanked by sociological passages. Mises does not draw clear lines of demarcation between economics and sociology; for him, the two disciplines are interwoven. His understanding of sociology is not the understanding common today; it is more akin to socioeconomic analysis. Hints of psychological argumentation appear when he addresses the envy and hatred as well as the resentment of the opponents of socialism (Mises 1922, 423). Mises did not consistently elaborate and apply his initial interdisciplinary approach, proposed in 1922 for the first time, which aimed at combining economic, sociological, and psychological theories.

In his 1927 book, Mises also chooses a special methodological approach. He combines economic considerations sporadically with psychological arguments (e.g., on the deeper psychological causes of resentment against capitalism, see Mises 1927, 12 ff.) and with sociologically based chapters (e.g., on human society and its emergence, see Mises 1927, 16).

Mises was not only a theorist of the market and economic constitution but also a social science theorist. For him, society was neither the struggle of all against all for existence nor the struggle of different classes, races, and nations against each other but a cooperative event in which the division of labor raises prosperity and enables individuals to achieve goals that they could not achieve alone. For Mises, society is thus not an end in itself but a means to the end of raising the prosperity of all (see Pies 2010, 12). Mises (2011, 155) explains society formation as a result of division of labor. Mises (2011, 153) also points out that the formation of a society does not result from conscious and goal-oriented actions but evolutionarily as an unintended by-product of individual actions.

One does not do justice to the writings of Mises presented here if one appreciates them as economic monographs and contributions. Mises is not only an economist but also deals with sociology, philosophy, history, epistemology, and philosophy of science (Polleit 2018, 232). He was an economist who was “aware of the need to link thinking and to relate epistemology, sociology, economics, and ethics to each other” (Engel 2010, 142). “Quite early on, he thus outlines the modern understanding of unified social sciences and a social science-oriented economics” (Schröder 2010, 205). His writings portray him not only as an economist but also as an intellectual and broadly interested scholar with an education in politics, history, social theory, and epistemology. His deep knowledge of the social sciences enabled Mises to recognize development trends in economics and society and to formulate accurate predictions. In his Socialism, Mises also thinks about the society in which socialism would be realized and comes to the conclusion that it would not have democratic but totalitarian features, because in socialism consumers are at the mercy of the power of the supply monopolists. According to Mises, socialism leads to democratic decisions neither in the economic process nor in politics (Pies 2010, 12). Mises’s prediction came true after World War II in all socialist countries. In January 1923, Mises (1923, 4) predicted an imminent collapse of the monetary system in states that chose deficit financing by printing money. His warnings proved to be accurate and were confirmed for Germany by the hyperinflation in the fall of 1923, which culminated in a currency reform on November 15, 1923. Mises (2011, 49) predicted that turning away from interventionist policies is a lengthy process: “Years would pass, even under the most favorable circumstances, before it would be possible to erase the traces of the mistaken policies of the last decades. But: there is no other path to rising prosperity for all.” His prognosis was confirmed by the difficult and time-consuming transformation process of former communistic economies in Eastern Europe after 1989.

2.7. On the Uniqueness of Mises’s Research Profile

Overall, it can be stated that Mises was a decidedly independent thinker who blazed his own scientific trail in economics, in the Austrian school of economics, and in the social sciences. His position in economics was outstanding because his research profile was unique. Mises’s positioning in his seven main research fields is only comparable with the research profiles of Marx, Hayek, and Schumpeter, who were, like Mises, also generalists with very broad spectrums of research topics. Specialized economists then and today cannot do research with such a broad scope. Mises intensively defended his positions and research results, which were contrary and opposing to neoclassical economics, the history school of economics, Keynesianism, and Marxism. His methodological positions and his praxeology approach were not accepted in mainstream economics. He was loosely linked to the Austrian school of economics, supported and applied the methodology (subjectivism, methodological individualism) of Austrian economics, but at the same time also criticized Hayek’s central positions. His familiarity with business administration principles and with managerial practice was very remarkable for an economist. Only very few economists of his time had comparable knowledge of the internal mechanisms and functioning of business firms and public authorities. And he even sought scientific dispute with Eugen Schmalenbach, the most famous business administration researcher of his time. Hayek never tried to start a scientific discussion with business administration researchers. Mises followed an interdisciplinary research approach encompassing economics, sociology, history, psychology, philosophy, and special aspects of business administration research. Therefore, he was much more than an economist. He was a theorist of human action and human society and one of the last polymaths with a primary anchoring and professional socialization in economics (see Pies 2010, 41). Taking all this together, Mises’s research profile and positions in economics can be judged as unique in the breadth and depth of topics he dealt with, his scientific positions, his methodology, his relative proximity to business practice and business administration, his independent position and partial emancipation from the Austrian school, and his interdisciplinary orientation. He was never able and willing to take a position in the mainstream of economics. His particular research profile makes his legacy works a mirror and a counterpoint deliberately set by him to the economic mainstream as defined then and still today by neoclassicism and Keynesianism. His work is today reduced by many experts to his fundamental critique of Marxism, socialism, interventionism, and etatism, but it contains at the same time a fundamental critique of neoclassicism—its equilibrium-oriented understanding of the market and its research methods and its narrow understanding of economics that ignores or disdains other disciplines and their insights.

3. Mises’s Position in Economics—an Isolated Position?

Mises increasingly had a more and more isolated position since the late 1920s in economics, which was characterized by the advance of Keynesianism and the belief in state control of the market. This isolation can be seen from four points: First, in his methodological position, which rejected empiricism, mathematics, and graphical representation, while, since World War I, economics had increasingly developed precisely in this methodological direction. Second, Mises’s minority position can be seen in his substantive positions, which, with his rejection of socialism and the welfare state or state control of the economy and his defense of liberalism, ran counter to developments in German society and in the discipline of economics since the First World War. Third, Mises’s isolated position is also reflected in his departure for Geneva, where he held a professorship in international economic relations from 1934 to 1940. From there he was forced by National Socialism to emigrate to the United States in 1940. In the US, Mises initially had great professional difficulties due to his poor English language skills, and he was forced to make a new professional start. Fourth, Mises’s position as an outsider is also reflected in the fact that he never held a full professorship in economics, neither in Vienna nor in the US, and that he conducted his research in Vienna as a private scholar who held an important professional position at the chamber of commerce.

Contrary to the facts presented above that seem to prove Mises’s isolation in the economics discipline are the following facts:

Ludwig von Mises’s books and his dedicated positions were cited, criticized, or affirmed in works of the economists, among them critics and opponents as well as admirers of Mises’s writings. The following list gives a first impression, showing that Mises’s works were read and cited by the most famous economists of his time. Therefore, he cannot be considered an outsider in economics.

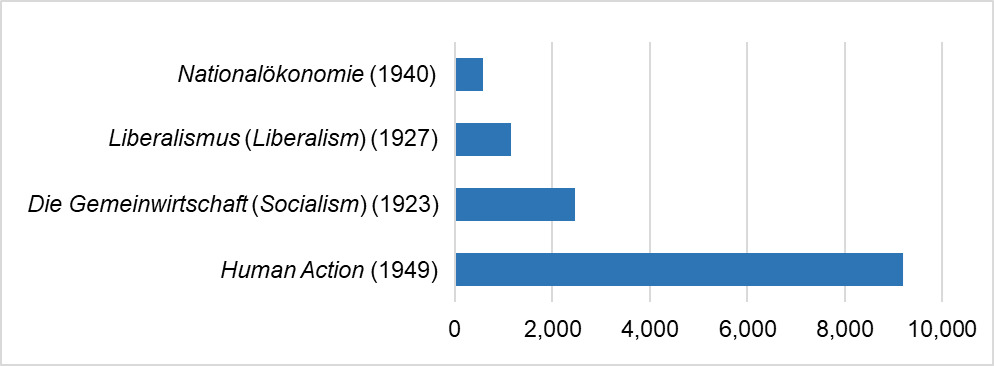

Mises’s writings are still widely read and cited today. There are divergent opinions as to which of his writings are the most important and significant. Almost all authors mention his book Socialism. According to Pies (2010), the most important works of Mises are Socialism, Liberalism, and, to a lesser extent, Nationalökonomie (National economy). The picture changes when one looks at the citations. The figure below shows how often Mises’s most important works are cited today. Outstanding here are Nationalökonomie (1940) and Human Action (1949). Human Action has become his most frequently cited publication. He published his magnum opus (Mises 1940) in his fifty-ninth year. Human Action summarizes and somewhat expands the essential insights of Mises’s early writings, research topics, and methodological positions. The work is rather summary in character and integrates all the topics Mises had dealt with in his writings in an overall context. The broad reception and success of Human Action is therefore an indicator that Mises’s writings are still relevant and read today. This fact is an argument that his position in economics is not isolated: he had an impact in this time, and he still has an impact today.

To judge Mises’s position in economics, it is also necessary to take into account his enormous impact on economic thinking and on economic policy in the past—maybe not at present but probably again in the future. Mises was not an outsider in economic theory and economic policy, because his books had a strong impact on economic theory and economic policy, especially in the 1920s. He made valuable contributions to Austria’s practical economic policy after World War I. The topics he worked on—state regulation, bureaucracy, liberalism and socialism, money creation and inflation, entrepreneurship and competition in markets, and the role of the state in the economy—have timeless character and timeless validity. At the same time, he built bridges to neighboring sciences such as history, philosophy, and sociology, entering into scientific discussions with other disciplines. None of the facts presented above are results and typical behavior of an outsider isolated from the world of science and the real world.

Mises had an inner circle of scholars, admirers, and supporters. This becomes evident if one looks at the personal help and financial support he received from colleagues and practitioners when he had personal problems after arriving in the US and initial difficulties with his second professional career at New York University. He sought academic exchange with colleagues from other disciplines (e.g., business administration and historians). He advised the Austrian government on public policy before and after World War I. Mises was adviser to the National Association of Manufacturers in the US from 1954 to 1955. He was awarded two honorary doctor of law degrees and one honorary doctor of political science degree. In 1962, he received an award from the Austrian government. In 1969, he was named a distinguished fellow of the American Economics Association. A total of three commemorative publications were written in his honor (on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his doctorate and on the occasions of his eightieth and ninetieth birthdays), with contributions from colleagues from all over the world (Moss 1976). All this shows that Mises had numerous professional relationships. None of these positions, recognitions, and honors could have been achieved by an economist working in isolation from the scientific community and society.

The above analysis leaves some questions unanswered. Central is the question of who holds the interpretive authority over the person and the scientific work of Mises today? His critics and opponents, as well as his followers and friends, are not suited for this task; a neutral third-party authority is needed.

This poses an evaluation problem of a special kind. In the course of the last one hundred years, the evaluation criteria for scientific achievements have changed. During Mises’s lifetime, what certified scientific quality were authored monographs and their impact on the discipline, appointments to well-known universities, the assumption of public offices and the chairmanship of scientific commissions and scientific associations, the founding of scientific societies, commemorative publications in honor of milestone birthdays and contributions by well-known representatives of the discipline to those publications, lectures and statements in the academic world, the consultation of princes and politicians and assumption of public offices, book reviews by relevant colleagues, and mention in the public press. Today, however, the evaluation criteria are partly different (e.g., number of citations in journals and impact factors) and the weighting of the factors is different than in the past. One does not do justice to Mises’s main publications and his position in economics if one uses today’s evaluation standards; the evaluation standards of his time must be used.