How do individuals calculate the prices of the assets they invest in? And on what criteria do they base the design and management of their portfolios? These are essential questions that different lines of economic research try to answer based on their conceptions of the actions of individuals and the characteristics of markets.

In this sense, we can list three primary schools for the systematic study of the financial behavior of individuals: neoclassical, behavioral, and Austrian, each of which contains a particular framework of analysis resulting in a different analysis of the behavior of assets and investors. Neoclassicals are marked by their objectivism, which considers markets to be efficient. For them, investors are risk-averse, and asset prices are linked to their risk. Therefore, portfolios are shaped with diversification to avoid correlated risks. On the other hand, the behavioral view considers individuals to be not rational and influenced by behavioral biases, which affect their decision-making and how they design their portfolios. Finally, Austrians have a more realistic perception of markets, understanding all purposeful action as rational, markets as a process in which individuals can learn, and the investor as an entrepreneur in the financial market who makes allocation decisions under uncertainty.

Behavioral finance highlights the role of psychological biases in investment decisions, adopting an evidence-based positivist approach to understanding human action. However, it does not consider individuals’ thymological ability to understand and reflect on facts and the social environment, gives little attention to exogenous factors influencing investment decisions, such as artificial economic cycles induced by monetary expansion, and does not encompass the concepts of valuation and appraisement in individuals’ investment actions. It misunderstands the formation of expectations and how investors analyze the future and make decisions about asset allocation and portfolio organization.

This article establishes an Austrian critique of behavioral finance using its theoretical subjectivist approach. While rejecting the rational maximizer of neoclassical finance, we find that behavioral finance overrates the role of psychological biases on investments. Lacking a proper comprehension of human action, they disregard subjectivism and individual learning. We make a comparative critique of these three schools of thought, working specifically on three points: market conception, asset pricing, and portfolio organization. This work contributes to establishing a comparative and systematic framework between the different schools and shaping an Austrian theory of asset selection and financial portfolio design. Also, it presents another face of behavioral finance, under a critique based on Austrian subjectivism, emphasizing the role of reflection and thymological comprehension in constructing an investment portfolio.

Understanding the Neoclassical and Behavioral Modeling for Finance

The Standard Neoclassical Model

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) posits that security prices in financial markets fully reflect all available information. This hypothesis suggests that it is impossible to consistently outperform the market through trading strategies based on existing information because prices adjust rapidly to new information (Fama 1970). The underlying idea is that asset prices already incorporate all available information in an efficient market, making it difficult for investors to gain a sustained advantage through trading decisions based on public information (Timmermann and Granger 2004).

According to the EMH, new information is quickly incorporated into stock prices, leaving no room for investors to identify undervalued or overvalued stocks consistently. This implies that even if investors use technical analysis (studying past stock prices) or fundamental analysis (analyzing financial information like earnings and asset values) to make trading decisions, they are unlikely to achieve returns greater than those obtained by randomly selecting a portfolio of individual stocks. The EMH suggests that if investors could consistently beat the market through trading strategies based on existing information, it would imply the existence of predictable patterns in stock prices. However, the hypothesis asserts that pricing in efficient markets follows a “random walk” pattern, where future price changes are independent of past price changes and reflect only new, unpredictable information. Therefore, even well-informed investors or experts may not be able to consistently outperform the market since any exploitable inefficiencies would quickly be eliminated by the actions of market participants, leading to prices that reflect all available information (Malkiel 2003).

There are essentially three forms of the EMH. The weak form, in which the information set is limited to historical prices; the semistrong form, in which the market incorporates all information that is publicly available at a given time, including past price history; and the strong form, in which all information known to anyone at a specific time is considered (Jensen 1978). These different forms of the EMH highlight varying levels of information incorporation in market behavior and efficiency. There is no evidence that deviations from the strong form of the efficient markets model permeate down any further through the investment community. For most investors, the efficient markets model seems a good first and second approximation to reality. In short, the evidence in support of the efficient markets model is extensive, and (somewhat uniquely in economics) contradictory evidence is sparse (Fama 1970).

After we have presented the EMH and explained its market assumptions, we must comprehend how individuals price assets. The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is significant for this subject. As asserted by Fama (1971), CAPM, also called the Sharpe-Lintner asset pricing model, was a natural extension of the portfolio models developed by H. M. Markowitz (1952; H. Markowitz 1959). Indeed, Fama (1968) presented no conflict between the models developed by William F. Sharpe and John Lintner.

However, the origins of CAPM are previous to the publication of Sharpe (1964) and Lintner (1965a, 1965b). Jack Treynor presented two manuscripts in 1961 and 1962 that were not published in academic journals. Indeed, even Fischer Black wrote a letter to Treynor in 1981 in which he assumed his creation of CAPM (French 2003).

And what are the bases of CAPM? Fama (1971) states that CAPM assumes a risk-averse market where consumers can make portfolio decisions based on means and standard deviations of one-period portfolio returns. More specifically, Fama (1968) explains that in Sharpe’s (1964) model, because all investors have the same horizontal and everybody sees portfolio opportunities identically, everybody faces the same picture of the set of efficient portfolios.

Perold (2004) clarifies that in CAPM, the discount rate to evaluate is determined by (1) the risk-free rate (Rf); (2) the market risk premium (Rm − Rf), the most challenging parameter to estimate since average returns being sensitive, long periods are recommended for measurements; and (3) the beta (β), estimated with the use of linear regression analysis applied to historic market returns data. The CAPM formula is as follows:

Ri=Rf+βi×(Rm−Rf)

Perold (2004) lists three main implications of the CAPM: (1) it aligns such that the return of an asset does not depend on its stand-alone risk; (2) the beta offers a methodology to analyze the asset risk that cannot be diversified; and (3) the stock return does not depend on the growth rate of its future cash flows. Investors do not need to develop complex valuation models, but they must estimate the beta, a more straightforward measure, to determine the performance of an asset.

And how can an abnormal return in a portfolio be explained using the CAPM? To answer this question, Jensen (1968) developed the concept of alpha (α). Jensen’s research considers data on 115 mutual funds and doubts that their returns originated from the portfolio manager’s ability to beat the market. Most of the return achieved by the funds was from the risk taken, not the managers’ ability to allocate their assets and design a portfolio. The ones that exceeded the market returns—namely, those whose portfolio returns were higher than the calculation of the CAPM of the portfolio—generated what he calls alpha.

As an alternative to the CAPM, Stephen Ross proposed in 1976 the arbitrage pricing theory (APT). APT is a multifactor model based on the relation between return and risk. However, it incorporates more factors that determine the price changes over time, called by the author sensitivities, as presented in the following APT calculation formula:

Rp=Rf+β1×f1+β2×f2+… βn×fn

These are not permanent sensitivities because they depend on the factors involved in each situation. (Ross 1976; Roll and Ross 1984). The theory’s assumptions are more straightforward but more difficult to apply because doing so requires more data control.

After understanding how asset prices are calculated within neoclassical finance, the last step in analyzing this investment paradigm is to explain how investment portfolios are put together. Harry Markowitz, in his article on portfolio selection, published in 1952, was the forerunner of what is known as modern portfolio theory (MPT). This article guided the development of portfolio allocation theory in mainstream finance.

The basic concept of MPT is quite simple. MPT theorizes that, given estimates of return, volatility, and correlation of a set of assets filtered by investment decisions, it is possible to reach an optimization of the relationship between risk and return (Fabozzi, Gupta, and Markowitz 2002). In this sense, in its most basic form, Fabozzi, Gupta, and Markowitz (2002) explain that MPT provides a structure for investors to construct and select portfolios. This construction and selection will be based on two key concepts: (1) the expected performance of the portfolio and (2) the investor’s risk appetite.

Another critical insight of MPT is the combination of risks and returns. In this sense, as explained by Perold (2004), while risks have a nonlinear combination, a consequence of the diversification carried out in the portfolio’s composition, returns combine linearly. Thus, the expected return is the weighted average of the expected returns for the selected assets (Perold 2004).

Based on the concept of covariance, H. M. Markowitz (1952) understood that different types of assets have risks correlated at certain levels (Perold 2004). Thus,

MPT quantified the concept of diversification, or “undiversification,” by introducing the statistical notion of covariance, or correlation. In essence, the adage means that putting all your money in investments that may all go broke simultaneously, i.e., whose returns are highly correlated, is not a prudent investment strategy—no matter how slight the chance is that any single investment will go broke. This is because if any single investment goes broke, it is very likely that the other investments will also go broke due to its high correlation with the other investments, leading to the entire portfolio breaking. (Fabozzi, Gupta, and Markowitz 2002)

The concept of covariance between different assets is so important that it will guide the risk measurement between assets. In this sense, H. M. Markowitz (1952) explains that

investors do not think that the adequacy of diversification depends solely on the number of different securities held. For example, a portfolio with sixty different rail-way securities would not be as well diversified as a portfolio of the same size with some railroad, some public utility, mining, various sorts of manufacturing, etc. The reason is that it is generally more likely for firms within the same industry to do poorly simultaneously than for firms in dissimilar industries. Similarly, in trying to make variance small, it is not enough to invest in many securities. It is necessary to avoid investing in securities with high covariances among themselves. We should diversify across industries because firms in different industries, especially industries with different economic characteristics, have lower covariances than firms within an industry. (H. M. Markowitz 1952)

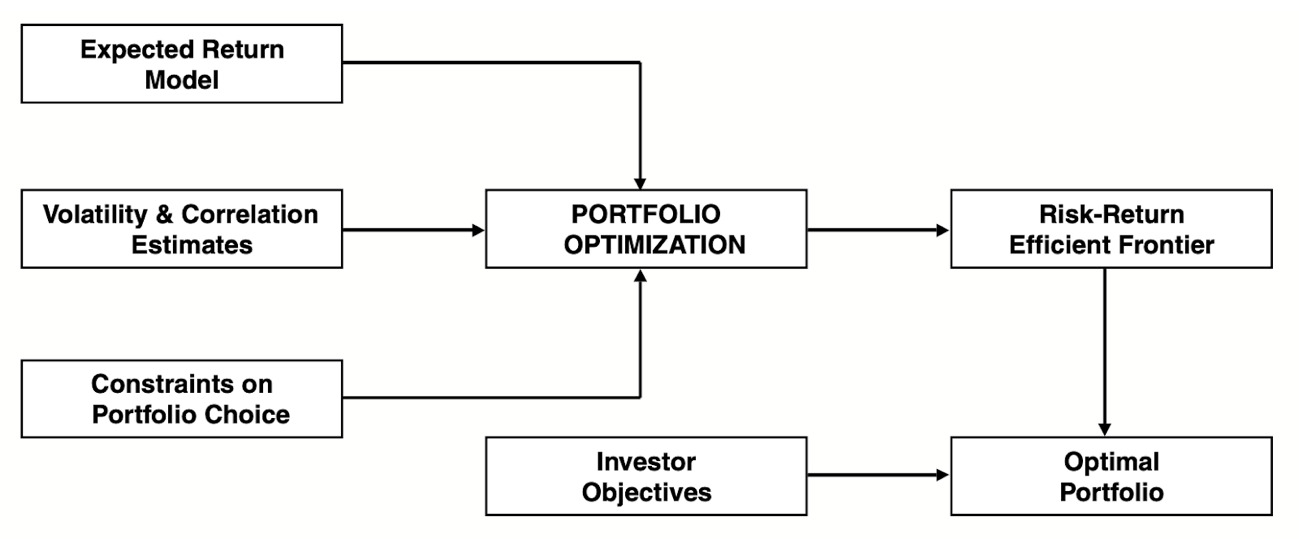

Following the innovative work of H. M. Markowitz (1952; H. Markowitz 1959), the MPT investment process was developed, as described in figure 1 below. It is important to note that this theory, through the concept of covariance and its application to portfolio diversification, has underpinned numerous innovations in finance, which are either the application of the idea of diversification or the introduction of new methods for obtaining improved estimates of variance and covariance, leading to a more accurate measure of risk (Fabozzi, Gupta, and Markowitz 2002).

Behavioral Finance

Following the previous characterization of the mainstream finance theory, we will present behavioral finance in this chapter. Behavioral finance appeared as a critique of the EMH, going beyond economic models by incorporating psychology to explain financial phenomena and market anomalies (see Shiller 2003). As behavioral finance focuses on psychological features to determine how individuals behave in the markets, it highlights the psychological aspects of market actions.

Baker and Ricciardi (2014) explain that behavioral finance attempts to combine psychology and investment both at a micro (decision processes of individuals) and a macro level (role of financial markets). One of behavioral finance’s main peculiarities is its understanding of human action in markets. Behavioral finance contrasts with MPT, rejecting the idea of rational investors (Statman 2008; Baker and Nofsinger 2002). Although behavioral finance aims to counter neoclassical finance, it does not reject neoclassical objectivist methodology. Indeed, as Shefrin and Statsman (1994) stated, the mere rejection of neoclassical rationality does not mean the rejection of empiricist methodology. Behavioral finance is still based on empirical tests and evidence.

Although both methodologies rely on empirical research, Holcombe (2009) notes differences. Neoclassical economics is grounded on a theoretical body of assumptions that guide its research. Behavioral economics uses empirical studies to validate or perceive flaws in standard economic theory. Behavioral research is not based on a prior conceptual framework that guides its studies; instead, it is based on the consideration that neoclassical economics is unrealistic and that its models are simple abstractions of reality (Holcombe 2009).

Behavioral finance establishes that investors are not rational decision-makers but “normal” (or “human”) individuals subject to effects other than the material economic-maximization decision (Statman 2004; Baker and Nofsinger 2002). In this sense, Kahneman (2003) considers individuals’ actions to involve bounded rationality. In neoclassical economics, individuals are systematically influenced by biases that hamper their ability to make rational decisions. Thus, individuals are partially rational, but their rationality is constrained by the biases that influence their behavior.

Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1991) clarify that these biases hamper rational maximization and lead to anomalies in individual decision-making. These anomalies are violations of standard neoclassical theory, and their inclusion in the theory would increase its complexity and decrease its prediction power. The authors advocate for replacing stable preferences with an understanding that preferences depend on the adopted reference level.

In relation to investment, behavioral finance considers more than the strictly rational expected returns when analyzing stock picking. For behaviorists, because psychological biases influence individuals, they are not pure maximizers. Behavioral finance explores other factors that influence human behavior. As Hirshleifer (2015) asserts, psychology has identified many biases that influence financial decision-making. Individuals are influenced by psychological biases that hamper the capacity to maximize the returns of their portfolios. Cognitive and emotional weakness plays a massive role in how people behave. As Baker and Nofsinger (2002) expound, although sometimes the departures from rationality are random, they are often systematic. Behavioral finance incorporates, through the combination of traditional (neoclassical) finance and psychology, these systematic human deviations from rationality to understand human financial behavior.

Baker and Rofsinger (2002) explain that behavioral finance examines how real people behave in finance. Hence, behavioral finance is a descriptive approach to understanding financial markets. Its proponents assert that people are not always rational but are always human. Statman (2008) identifies four main assumptions (foundation blocks) guiding behavioral finance research: (1) people are “normal,” not rational; (2) markets are not efficient as described by traditional finance; (3) investors design their portfolios based on behavioral portfolio theory; and (4) expected returns are based on more than risk.

For behavioral finance, investing is more than just analyzing numbers: individual behavior is also involved. If ignored, such behavior can influence portfolio performance. Behavioral finance examines mental and emotional processes that investors reveal during the investment process (Baker and Ricciardi 2014).

Behavioral finance does not focus on past information, assuming that all information is given and available for investors. As Bogatyrev (2019) explains, behavioral finance focuses on the new information generated in the market process and how this information is interpreted by nonrational (human or average) players.

To analyze how investors act in markets (picking, pricing, and trading stocks), behavioral finance stresses the role of psychological biases. These influence investment decisions, conditioning investors’ actions in the markets and the course of investment assets.

Sheffrin and Statman (1994) differentiate between rational and noise traders. Noise traders are those who submit to psychological biases and introduce inefficiency to markets. They are not maximizer allocators like the neoclassical rational investors. By including noise traders in the trading process, (1) it is costly and risky to bet against them because their behavior is unpredictable (see Shleifer and Vishny 1997) and (2) there are limits to arbitrage.

Baker and Ricciardi (2014) give eight examples of psychological (emotional or cognitive) biases that influence investment behavior in markets: (1) representativeness, in which investment decision is based on past performance; (2) regret (loss aversion)—that is, people regret their bad decisions because it generates bad feedback; (3) disposition effect, a tendency to sell winner stocks in the short term while holding losing stocks in the long term; (4) familiarity bias, in which investors prefer familiar investments despite gains from diversification; (5) worry, which affects how people perceive risk; (6) anchoring, in which investors hold a belief that will serve as a base for their future subjective decisions; (7) self-attribution bias—that is, investors trust success comes from their actions while failures come from external factors; and (8) trading chase bias, in which investors try to guide their investments through trends.

These biases are extrapolated from specific financial research and influence the subject. In their turn, Samuelson and Zeckauser (1988) present the status quo bias, which describes individuals having some inertia—that is, preferring to maintain a previous situation rather than changing it. Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1991) see the status quo bias as a consequence of loss aversion.

Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1991) also explain the endowment effect, which is also relevant for portfolio organization. The endowment effect, in essence, claims that people tend to value a good more if they own it compared to a scenario in which they do not own the good. This effect is evidence, for them, of how the concept of stable preferences is not evidenced in practice.

Qadan and Jacob (2022) explain a particularity of behavioral finance: besides all these psychological biases hindering rational (in the neoclassical sense) investment decisions, there is also a long-term trend toward market values reverting to intrinsic values. However, it is impossible to foresee when this will be a reality.

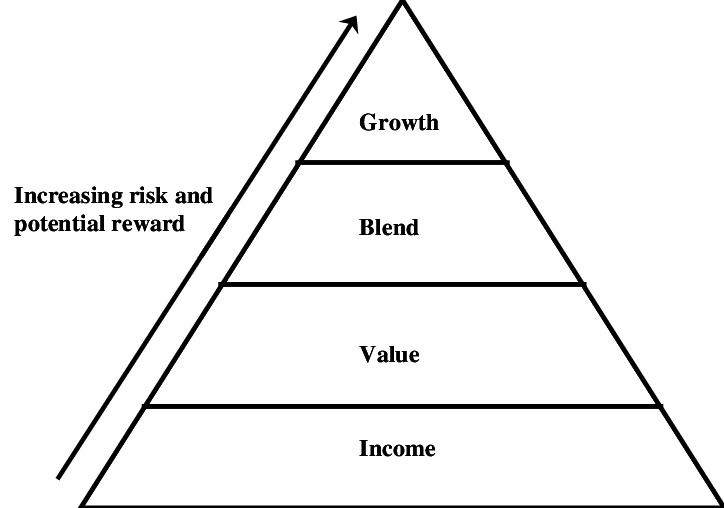

Shefrin and Statman (2000) present a model for portfolio management under the assumptions of behavioral finance called behavioral portfolio theory. Investors have more than one global portfolio: their portfolios are aggregates of subportfolios optimized for particular mental accounts. Furthermore, each subportfolio has a certain level of risk tolerance besides a specific goal. Investors divide their money into different layers, each established to achieve one goal. Moreover, each layer has a different aspiration, risk, and profit expectation (Sheffrin and Statman 2000; Statman 2004).

While talking about behavioral portfolio management, it must be understood that investors have more than a single goal, as in traditional finance (maximizing returns at a particular risk level), but several goals guided by their emotions, needs, desires, habits, and biases (Shefrin and Statman 2000; Statman 2004).

The optimal portfolios are not built as single optimal portfolios but as combinations of subportfolios. Moreover, they maximize more than mere monetary utility; they also maximize investors’ emotional and expressive utility (Shefrin and Statman 2000; Statman 2004).

Statman (2004) presents the behavioral portfolio as a pyramid (figure 2). In this pyramid, each level works as an independent subportfolio, a building block to achieve the particular goals of the investor. Investors have levels of concern and objectives that help them allocate their assets and organize their portfolios.

The Austrian Alternative

The Market as a Process over Time

Austrians adopt a more comprehensive comprehension of human action—and what rationality is. As Mises (1998, 19–22) explains, all human actions are rational. Human action is a concrete act to improve individual satisfaction (Rapp, Olbrich, and Venitz 2017). Individuals have subjective perceived ends and act to pursue them. Thus, human action is purposeful behavior, attempting to exchange a less satisfactory state of affairs for a more acceptable state (M. Rothbard 2009, 19).

With the Austrian understanding of rationality, it is possible to see how individuals make self-interested decisions simultaneously. Biases influence them. Austrians do not analyze actions in a mechanistic sense. For Austrians, people are influenced by more than just an attempt to maximize their monetary returns. Also, Austrians do not take for granted that biases influence human action. Austrians understand that biases affect individual decisions but do not see biases as immutable structures of the mind.

In the investors’ behavior, it must be considered that individuals can learn. Through trial and error, society evolves. Individuals use their ability to acquire thymological comprehension and perceive market behavior patterns. People learn; when they do, they can act differently and change history. Thus, people can perceive biases and understand how they guide their actions.

The Austrian understanding of the market as a process is one of the particularities that result from its conception of human action and science. As Horwitz (1994) explains, the market is a process of creation and use of knowledge. Mises (1998) defines the market as the social system of the division of labor under private ownership of the means of production, with no compulsion or coercion. It is not a place or a collective but a process resulting from human action, the convergence of different individual actions, all based on monetary economic calculation.

Mises states that markets are the product of cooperation and competition. Social competition differs from biological competition, which is permanently restricted by the scarcity of economic goods and services. Catalytic competition safeguards the best satisfaction of the consumers in the present state of the economy (Mises 1998). As the market is considered a process, time is essential. In Human Action, Mises states that change presupposes understanding temporal sequence. More than that, actions always happen at a particular time, the present, but aim to change future situations. The present exists and was built in the past. In the present, we make the decisions and actions that change the future (Mises 1998).

Time is essential not just to the organization of capital but also to the acquisition of subjective knowledge. Mises (2007) explains how people, over time, evaluate actions and use their thymology to understand behavior patterns, following past examples and their adaptations. Expectations (or knowledge about the future) must be understood as subjective information that individuals possess due to reflections about the future, related to the present state of affairs.

As actions happen over time, people adjust and readjust their actions to achieve better results. To make coordination between isolated self-interested actions possible, people develop institutions (such as money, markets, prices, and law) to reduce uncertainty and make decision-making better and more transparent.

Future values are unknown in a dynamic real world. They are just estimated by the entrepreneur who speculates about the future. For him, entrepreneurs practice arbitrage, and the quality of their forecasts is an essential part of their income (M. Rothbard 2009, 509–55). New techniques become profitable if they improve consumer satisfaction. He did not deny the relevance of innovation but criticized the stress Schumpeter put on it. For him, innovation is one of the entrepreneurial tasks. Entrepreneurship depends on uncertainty, and so entrepreneurs adjust to discrepancies. When they innovate, they are adjusting (M. Rothbard 2009, 509–55).

Rothbard recognizes that the quality of forecasts is what drives profits and losses. Continuing the Misesian understanding of the market process, Rothbard considers permanent uncertainty a crucial feature. Adopting a more subjective realistic understanding of human coordination than Hayek and Kirzner, he does not believe that people apply themselves to adjust “misspecification” and miscoordinations but rather that they create future prices with their actions.

A Critique of Asset Pricing in Neoclassical and Behavioral Approaches

As explained above, markets are a creation process over time, with unknown conditions. Individuals have estimations and expectations, speculating what will happen. No one controls the future, which depends on individuals’ sovereign subjective actions. Thus, the idea of situations conditioned by past returns and volatility is absurd under Austrian assumptions.

The same can be established in relation to APT. Although assets have, of course, a different sensibility for each factor of the economy, it must be understood that past sensibility is historical data and not a determinant of future sensibility. Besides being a more complex calculation, APT has the same flaws as CAPM.

Indeed, it is impossible to predict that assets will keep the same trading pattern over time. How could someone assert that beta, even if the assertion is based on long-term past calculations? The market changes, and the business industries that command leading growth and development change over time. The future is a creation and not a repetition of past conditions.

As Mises (2007) explains, individuals learn from history, understanding patterns of behavior that can be repeated over time in a process called thymological comprehension. They get some bites of other people’s subjectivity; however, this is neither an objective nor a deterministic activity. Furthermore, the idea of a return based on the assumed risk is absurd under Austrian terms. The return on investment is never related to conditions of risk and uncertainty but to entrepreneurial ability to forecast the future. Uncertainty (and not risk, as considered by neoclassicals) is always present in different grades.

Regarding behavioral finance, Austrians do not consider psychology (or its effects) to be what conditions human behavior in markets. Of course, biases influence investors’ behavior in markets, but these are part of human behavior and do not thoroughly condition their actions. Individuals can, over time, understand the existence and the patterns of these bias phenomena, avoiding them and their effects on their investment actions.

Austrians do not deny the existence of biases and their role in investors’ decisions. Adopting a broader concept of rationality, Austrians indeed include biases in rational decision-making. Biases do not violate the Austrian idea of rationality but are part of the subjective framework that guides the individual’s choices. Biases also do not hinder the possibility of achieving the desired end, since ends are subjective and depend on many factors exceeding mere monetary maximization, including security and peace of mind. Even with biases, individuals seek a better state in their subjective terms.

Moreover, Austrians do not adopt a mechanistic or deterministic position on biases. Biases, as features of the human mind demonstrated in past actions, can be understood and avoided in the future. One essential characteristic of individuals’ choices and actions is reflection on facts, using a thymological ability to perceive patterns and their evolutions over time, in order to achieve a more satisfactory state.

If psychological biases could fully condition people, they would act in a mechanistic (chaotic) way. Their minds would be determined, unable to change the course of history. Biases would be the ultimate givens, and any efforts against them would be fruitless. They would constrain human action in the same way instincts determine animal reactions. Moreover, people would not perceive opportunities to act to create new causes and consequences and act entrepreneurially.

Appraisement and Valuation in Economic Calculation

And how do individuals make their decisions? Herbener and Rapp (2016) state that investment decisions involve valuation and appraisement. Appraisement estimates future prices and conditions (Mises 1998, 329). Appraisements are anticipations of prices. They are attempts to forecast future prices to determine the individual’s actions. Investors need to identify an asset’s possible future benefits to establish its adequate, reasonable evaluation. Appraisement will guide the productive plans for entrepreneurs and the asset allocation (portfolio organization) for investors.

Herbener and Rapp (2016) assert that not every appraisement requires a formal calculation, especially in everyday situations; however, entrepreneurs and capitalists cannot give up these calculations to compare alternatives. Any personal valuation without appraisement is a blind guess about the future. In these cases, appraisement also involves an attempt to anticipate the effects of monetary policy.

Authors such as Salerno (1990, 1993, 1994) and M. N. Rothbard (1991) show that individual appraisements are the basis of what Mises calls economic calculation. Mises did not intend to talk about economic calculations based on past prices. This position contrasts with the Hayekian consideration. Mises, in Human Action, is clear that any action is always future-oriented. Thus, calculations look at future prices, estimating them to establish a table of preferences and the designation of means to achieve them. The problem of socialism was not a problem of knowledge dispersion but a problem of calculation—that is, an issue of estimating and forecasting future prices to organize resource allocation.

As Salerno (1994) explains, the argument that Salerno, Rothbard, and Herbener had about economic calculation involved two main points: (1) the market creates a social appraisement process, dependent on the intellectual division of labor, based on qualitative understanding, and not included in informational parameters of the equation system; and (2) this process is crucial to convert multidimensional knowledge to economic data in a structured unit of prices for economic goods (resources and products).

Appraisements are estimations of future prices. They use a combination of thymological analysis to foresee what prices will appear in the markets. Investors understand behavior patterns, market trends, and new emerging phenomena to mold their considerations of future prices. Appraisement does not depend on individual valuation. Estimates on future prices do not rely on people’s evaluations. Appraisement is an autonomous activity.

In turn, valuation is the choice between individual preferences for the most valued ends. Valuation is always individual, and each person has different valuations and a particular order of preferences. Valuation is a value judgment (Mises 1998, 329), a selection process in which individuals identify their most valuable ends.

Personal valuation in an autistic economy would be sufficient for the individual, since he would not interact with other people. Nevertheless, appraisement is required in a market economy in which the individual relates to others in a productive process (Mises 1998; Herbener and Rapp 2016; Rapp, Olbrich, and Venitz 2017). In a market social order based on the division of labor, people interact and exchange goods to satisfy their needs.

As M. Rothbard (2009, 279–80) asserts, the existence of monetary means to make exchanges easier expands the possibilities of individual choice. People are not limited to direct exchange, in which they need to find a counterpart in a costly and lengthy process. Using money, individuals allocate means to achieve the ends they value more. These ends are not based on the present situation but are always looking at the individuals’ expectations about the future based on ex ante appraisements.

If people always make some (even tacit) appraisement, it is impossible to state that portfolio or asset allocation is determined by psychological biases. Psychological bias can play a role in investors’ actions, but it is not the primary motivator of investment decisions. People always establish a relation between actual prices and future prices, trying to forecast the future of markets. While trying to forecast future prices, investors implicitly attempt to predict the future behavior of other investors. They try to guess which psychological biases will be presented in other investors’ decisions.

People learn from experience and can identify these biases and the consequences they will generate for individuals’ actions. Successful investors recognize the subjective formation of prices over time. Also, since biases play a role in investment behavior, investors can reflect and attempt to forecast the pattern of biases’ effects on investment activities.

Portfolio Design under Austrian Assumptions

Now that we have understood how Austrians predict the value of financial assets, we need to explain how a portfolio is designed on an Austrian basis such that it fundamentally differs from portfolios designed under neoclassical and behavioral precepts.

Firstly, for Austrians, the investor is never a passive individual who assembles portfolios reactively to external conditions, such as perfectly estimated risk in the market. Individuals are agents, not reactors. In a world of conditions never given and always to be made, the investor is a financial market entrepreneur who makes resource allocation decisions under uncertainty, making judgments about the use of the scarce resources at his disposal (Knight 1921; Foss and Klein 2012).

In this sense, the investor is the ultimate judge, even if he hires managers or advisors. This is because, as an entrepreneur, he has the original power of judgment and can, depending on the terms of the contracts established, delegate part of his functions and revoke the mandates he creates with these third parties (Klein and Foss 2012).

As much as investors fear uncertainty, there is no avoiding it. Even those who consider themselves risk-free face uncertainty. The government can inflate the currency to pay off its debts, and for short-term bonds the horizon of uncertainty faced is shorter.

As an entrepreneur, the investor lists his goals, establishing objectives and priorities that will guide the formulation of his portfolio. After this, based on his assessments of market prices (whether this is the process of future prices for assets or the subjective costs he will incur), he designs a portfolio to achieve the objectives he has set. He will make judgments regarding the use of his financial resources under conditions of uncertainty. It should be remembered that this will always be guided by the investor’s ex ante assessments, which, in the realization of the facts, may prove to be unsuccessful.

Additionally, investors use their ability to learn, understand the facts, and experience to manage their portfolios dynamically and efficiently. Over time, the investor adjusts his capacity, understands his biases, reshapes his objectives, and reconsiders the appropriate means to achieve them, thus changing the composition of his portfolio.

With regard to diversification, it is not theoretically possible to know the optimum number of shares to include in a portfolio. Like all economic goods, financial assets are subject to diminishing marginal utility, which impacts the development of a portfolio and even implicitly restricts the formation of a highly pulverized portfolio. In Austrian terms, even the concept that there is no more appropriate portfolio than the market itself is illogical since diversification beyond a specific limit generates little or no benefit, given the diminishing marginal utility.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The purpose of this article is to make a comparative critique of these three schools of thought, working specifically on three points: market conception, asset pricing, and portfolio organization.

The EMH posits that financial market prices fully reflect all available information, making it impossible for investors to consistently outperform the market using trading strategies based on this information. Since asset prices already incorporate all available information, technical and fundamental analyses are unlikely to yield returns higher than those of a randomly selected portfolio. MPT provides a framework for constructing investment portfolios that optimize the relationship between risk and return. Although initially not impactful, it later became fundamental in mainstream finance. MPT suggests that by estimating the return, volatility, and correlation of a set of assets, investors can create optimized portfolios that balance expected performance with their risk appetites. A critical insight of MPT is that while returns combine linearly, risks combine nonlinearly due to diversification. This diversification is quantified using the statistical notion of covariance, which measures the correlation between asset risks. The theory posits that a well-diversified portfolio should include assets from different industries to minimize risk, since assets within the same sector are likely to perform poorly simultaneously. MPT’s principles have led to various financial innovations that focus on diversification and improved risk measurement through better estimates of variance and covariance.

The Austrian perspective on markets and investment differs significantly from neoclassical and behavioral approaches. Austrians view the market as a dynamic process driven by human action over time, where all human actions are rational and purposeful, aiming to improve individual satisfaction. Biases influence decisions, but individuals can learn and adapt, recognizing and mitigating these biases through experience and reflection. The market is seen as a process of cooperation and competition, evolving through the creation and use of knowledge. This perspective emphasizes the importance of time, as actions aim to change future conditions based on current decisions.

According to the Austrian school, investment decisions involve valuation and appraisement. Individuals estimate future prices and conditions to guide their actions. Unlike neoclassical finance, which relies on past data to predict future returns and risk, Austrians argue that future values are unpredictable and depend on subjective actions. This critique extends to asset pricing models like CAPM and APT, which Austrians find flawed due to their reliance on historical data.

In designing portfolios, Austrians see investors as proactive entrepreneurs making judgments under uncertainty. They dynamically manage their portfolios based on their goals and market assessments, and they learn from experience. Diversification is acknowledged, but its optimal level is not predefined, given the diminishing marginal utility of financial assets.

The Austrian view of human action and rationality is that all actions are rational and purposeful, driven by subjective goals. This contrasts with neoclassical and behavioral models, which often see rationality in more constrained or mechanical terms, with biases viewed as deterministic constraints. Austrians know the market as an ongoing process influenced by human action, knowledge creation, and competition. Neoclassical models view markets as static or equilibrium-focused, while behavioral models emphasize the influence of psychological factors on market behavior.

Time is central to the Austrian view, which focuses on future-oriented actions and the inherent uncertainty of future conditions. Neoclassical finance often relies on historical data and statistical models to predict future outcomes, assuming some predictability and risk management. Austrian theory emphasizes subjective valuation and appraisement based on future expectations. In contrast, neoclassical models use objective calculations based on historical data, and behavioral finance incorporates psychological biases into decision-making frameworks.

Austrians see investors as entrepreneurs who actively manage portfolios based on their subjective goals and market assessments. Neoclassical finance relies on models like CAPM to determine optimal portfolios based on risk and return, while behavioral finance considers how psychological biases affect portfolio choices. Austrians acknowledge biases but believe individuals can learn and adapt to mitigate them. Behavioral finance emphasizes how biases systematically affect decision-making, often viewing them as more persistent and challenging to overcome.

This work contributes to establishing a comparative and systematic framework between the different schools and shaping an Austrian theory of asset selection and financial portfolio design. The article also presents another face of behavioral biases, criticizing them under an Austrian subjectivism, emphasizing the role of reflection and thymological comprehension in constructing an investment portfolio.